The best-known of these caves are the mystical Ægissíðuhellar - Hellarnir á Hellu - the Caves of Hella. They are among the largest man-made caves in Iceland.

I joined two guided tours of the caves to learn as much as possible about their origin, which remains a mystery to us.

Top photo: Inside the Caves of Hella - a passageway between two caves

Inside the caves of Hella - Fjóshellir

Through the years, I have written about many of Iceland's caves, some of which are very difficult to enter, like Lofthellir cave up north, so I was glad that the Caves of Hella are easily accessible.

Remember my travel blog about the longest man-made cave in Iceland - Hellnahellir cave?

The Caves of Hella are in that same category and are most likely amongst the oldest still-standing structures in Iceland.

These caves are truly a historical wonder, but who built them, and when?

A cross carved into the cave wall

A cross carved into the cave wall

To be honest, we have no idea, but there are some speculations that they might even predate the Viking settlement of Iceland around 874 AD.

There are many engravings on the cave walls, including several crosses, so we know that the people who used them were Christian, but the majority of the Norwegian settlers were heathen.

The Landnámabók - the Book of Settlement of Iceland, tells us that there were some Irish monks called Papar living in Iceland when the Vikings arrived. They were no fans of the Vikings, so they left.

And who can blame them, given how the Vikings had treated the monks in England, remember the Viking attack on Lindisfarne in 793?

The entrance to Fjárhellir cave

The same family has taken care of the Caves of Hella for almost 200 years, the farmers at Ægissíða farm.

The family wanted to show these remarkable caves on their land to the public, and in cooperation and under the supervision of Minjastofnun - the Cultural Heritage Agency of Iceland, they rinsed out the caves and restored them.

In 2019, the owners of the Caves of Hella opened 4 of the 12 known caves to the public and offered guided tours of them. Kudos to them for a job well done. I, for one, am glad that I was able to visit these amazing caves.

Carvings on the walls in the Caves of Hella

Carvings on the walls in the Caves of Hella

The proceeds from the admission fee go toward restoring more caves, and, hopefully, some of them will be accessible to the public in the near future.

One of the owners of the caves, Professor Baldur Þórhallsson, has guided in the caves since he was 5-6 years old, and his grandfather guided tourists in the caves.

Baldur grew up at Ægissíða and is very knowledgeable about these historical caves. At that time, half of the caves were in use by his grandparents and parents.

And, he was a firm believer in the Irish settlement before the settlement of the Vikings back in 874, and that the Irish had made these caves.

Crosses carved into the sandstone walls of the caves

Crosses carved into the sandstone walls of the caves

On the guided tour of the caves, the guides will tell you stories about their mystical past and the engravings on the sandstone walls.

And how the farmers used these caves as sheep sheds, dwellings, and hay storage.

Sandstone is watertight, unlike the lava caves, so it was an ideal place to live, store hay, livestock, or food. And remember that Icelanders lived in turf houses back then, which needed constant maintenance.

The sandstone caves seem to withstand earthquakes, given that they are properly maintained, but in this area, we experience the so-called Suðurlandsskjálfti - the Southern region earthquake every 100 years or so.

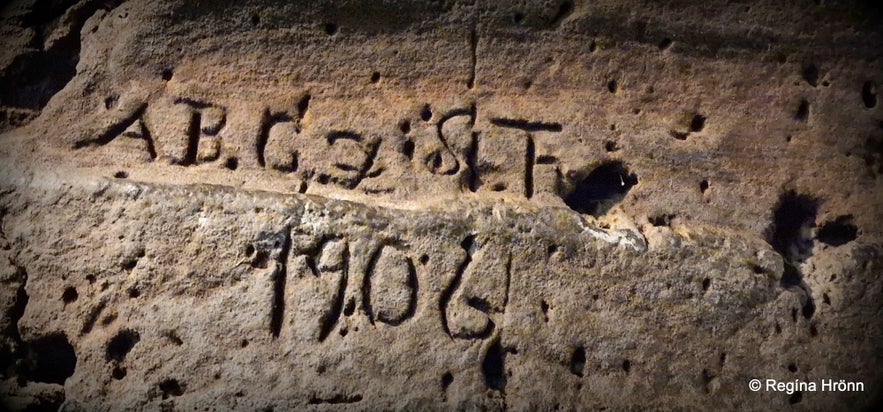

Names and dates are carved on the sandstone walls of Hlöðuhellir cave

Names and dates are carved on the sandstone walls of Hlöðuhellir cave

The Caves of Hella are collectively called Ægissíðuhellar, as I mentioned earlier. It is believed that there are 18 man-made caves at Ægissíða, 12 of which are now known.

The earliest written mention of these caves is an old rhyme from the latter part of the 18th century, in which Guðlaug Stefánsdóttir from Selkot mentions 18 caves at Ægissíða.

The name Ægissíða, translated into English, means by the sea (ægir is one of the Icelandic names we use for the sea). But the sea is far away from the caves, so why is it called Ægissíða?

The entrance to one of the caves

The entrance to one of the caves

There are speculations that this name is of Celtic origin (Gaelic) and means "the people who live in caves" or "the people who live in man-made caves."

Other speculations in our folklore hold that they were called Ærsíða (ær meaning ewe), and one of our tales explains the name.

I like to believe that the word is of Gaelic origin, but many Icelandic words are of Gaelic origin.

Genealogy shows that Icelanders are descendants of both the Nordic settlers and the Irish.

40-60 percent of Icelanders might be of Irish and Scottish origin. New DNA tests have shown that 20 percent of Icelandic men and 60 percent of Icelandic women have such genes.

The Vikings brought Irish thralls, but there are indications that an Irish population was already in Iceland.

The Irish adopted Christianity centuries before the Norwegians (Icelanders) did, and they possessed the know-how to sail to Iceland long before Iceland's settlement began.

And, the Irish St. Brendan the navigator (484-577) seems to have sailed to Iceland in 548.

So these extraordinary caves might predate the settlement of Iceland, even though that part of my country's history is lost, and we only have bits and pieces we are trying to puzzle together.

Engravings on the walls of Hlöðuhellir cave

Engravings on the walls of Hlöðuhellir cave

Later in this travel blog, I will tell you what sources we have about the Irish.

We hope that with time, we will find more evidence that our ancestors were not only Viking settlers but also Christian Celts whose story has been lost.

Fjárhellir and Hlöðuhellir caves

Our guide, Rökkvi, lit up some of the engravings on the walls in the caves

Our guide and friend Rökkvi sometimes guides in the Caves of Hella, and he invited us to join him on a tour.

He first showed us Fjárhellir cave - the Cave of the Sheep and used a flashlight to light up the engravings on the walls.

There are many engravings on the cave walls. It is very interesting to examine the names, dates, initials, and symbols carved into the sandstone walls.

Some of the engravings are very old; others are younger, as it were. Some of the strange signs you will see in such caves are house marks (búmerki).

On a guided tour of the Caves of Hella

On a guided tour of the Caves of Hella

Some of them look strange to a city dweller and remind me of runes and magical staves.

In this cave, there was an opening in the ceiling, a chimney, through which light poured into the cave, and air, and if a fire were lit inside the cave, it would let out the smoke.

Such openings were also used to throw hay into the caves.

I also saw an old well, but these wells are not ancient; the oldest ones seem to date back to the 19th century.

After examining Fjárhellir cave, we entered Hlöðuhellir via a narrow passageway between the caves. It is a 10-meter-long carved tunnel, carved in 1927.

The passageway between the two caves is narrow but lit up

The passageway between the two caves is narrow but lit up

It is lit and easy to pass, but if you are claustrophobic, you can exit the cave and enter Hlöðuhellir from the outside.

There are a myriad of dates, signs, and names carved into the walls of Hlöðuhellir cave, including the year 1913, which stands out.

This was the year that this cave was discovered. A small boy crawled into the cave and measured it to be 11 meters long.

In 1916, when Minjastofnun and the cave's owners dug it out, it turned out to be twice as long, at 22 meters.

A date carved into the wall, it is out of focus, though, as it is so difficult to take photos inside the cave

It seems his cave was used to store hay and later potatoes. In 1967, the cave entrance was widened to allow a tractor to enter.

When you see the concrete entrance from the outside, you have no idea that a historic cave is hidden behind it.

I had seen this entrance from the road when we were passing by and thought that it was a storage of some sort with grass on top.

The entrance to Hlöðuhellir cave

The entrance to Hlöðuhellir cave

It is a bit tricky taking photos inside caves, should I use flash or no flash? I opted for using the flash.

Unfortunately, many of my photos are out of focus. I took pictures with three cameras and my phone, but none of them turned out well.

There is a special engraving in Hlöðuhellir cave, which you can see in my photo below, and the guide told us that it looks a bit like Arhus Vikingen masken.

A strange engraving on the walls of Hlöðuhellir cave

There are many cross-carvings in the Caves of Hella. Here we spotted two crosses, but surely there were more that we didn't notice in the darkness.

In Hlöðuhellir cave, in one of the side caves, you will find barrels of Icelandic whiskey from Eimverk distillery, where my husband and the guide Rökkvi offer very popular whiskey distillery tours (you will get to taste 11 different types of their products).

The Flóki whiskey from Eimverk is the only Icelandic whiskey made with all Icelandic ingredients - from grain to glass. And the fields are at Bjálmholt farm in the vicinity of the Caves of Hella.

Hellaviskí - Cave whiskey from Eimverk distillery

If you book a luxury tour of the Caves of Hella, you will get to taste the Flóki whiskey, together with beer sampling and tasting of local delicacies.

There are speculations about whether this side cave had a curtain, as there are signs of ropes being used in this cave.

After examining Fjárhellir and Hlöðuhellir, we crossed the field and walked to Fjóshellir cave with our guide Rökkvi. It is one of the largest caves in the Caves at Hella.

Other caves at Hella are called Lambahellar, Kirkjuhellir, Brunnhellir, Búrhellir, Hrútshellir, and Skagahellir.

I took a short video of the surroundings when we were standing next to Kirkjuhellir cave

We stopped by Kirkjuhellir - the Church cave, which was closed. I would love to enter it one day.

A Catholic mass was held here in Kirkjuhellir cave back in 1950.

Brunnhellir, the Cave of the Well, was discovered in 1907 when a horse stepped into a hole, and I think it fell into the cave.

Food is stored in the small Skagahellir cave

Food is stored in the small Skagahellir cave

On the way to Hlöðuhellir cave, we peeked into Skagahellir, which is now used as a food storage room.

Skagahellir was also used as an icehouse at some time, and food was stored in some of the caves.

We now entered Fjóshellir cave.

Fjóshellir cave

Fjóshellir cave and the Chapel

Fjóshellir cave and the Chapel

The name of the cave, Fjóshellir - the Cowshed Cave, describes the use the farmer had of the cave, although he did not use it to keep his cows, but as a storage room for hay.

A tunnel led from the cave to the cow barn, which was in use until 1975.

The farmers stopped using the caves in the 1980s, and they remained abandoned until Baldur and his family restored them and opened them to the public.

A lot of work was required to restore the caves; they were cleaned out, and the entrances and stone chimneys were rebuilt with a glass ceiling. And lights were added to the caves.

Our guide showed us short tracks in the cave

Our guide told us about the prominent tracks in Fjóshellir cave. A cart was used to carry the hay from the cave into the cowshed.

These tracks previously carried the only train in Iceland (a very small one), which transported rocks for the old Reykjavíkurhöfn harbour.

There are two openings in the ceiling of Fjóshellir cave, chimneys, much like the chimneys I showed you in Hellnahellir cave.

Hey was also thrown into the cave through these openings.

Tracks in Fjóshellir cave

To me, the most interesting part of Fjóshellir cave is Kapellan, the Chapel. It for sure looks like a place of worship, with two sets of steps leading up to it.

It is mysterious visiting the caves; it is cold inside, so that a blue mist can be seen in some of my photos. Dress accordingly when visiting the caves.

In the Chapel, there is a beautiful embossed cross. This might have been the altar's location.

We are just speculating, but when you visit the Caves of Hella, you will see why.

It is one of only a few embossed crosses we have found so far in Icelandic caves, and it might have been a Corpus Christi.

There are openings in the ceiling of the cave

No Celtic crosses have been found in the man-made caves in Iceland, though.

Crosses have been carved into the walls of many other caves in South Iceland, and to me, they speak volumes.

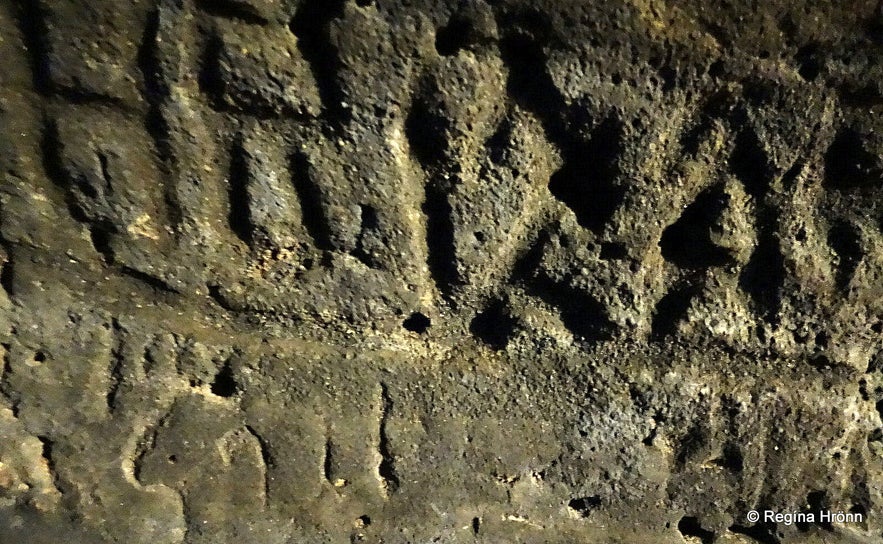

In Fjóshellir cave, you will also see engravings that our beloved poet and sheriff in Rangárvallasýsla county, Einar Benediktsson (1864-1940), thought resembled Ogham engravings.

He was an enthusiast of the Irish settlement before Iceland's settlement, and he examined many of the man-made caves.

An embossed cross in the Fjóshellir cave

Ogham is an ancient Irish alphabet and could only have been made by the Irish (Celtic people).

These engravings are very faded, though, from when hay was kept in the caves, and I could not photograph the engravings with any of my cameras.

But I add them anyway so that you can judge for yourself.

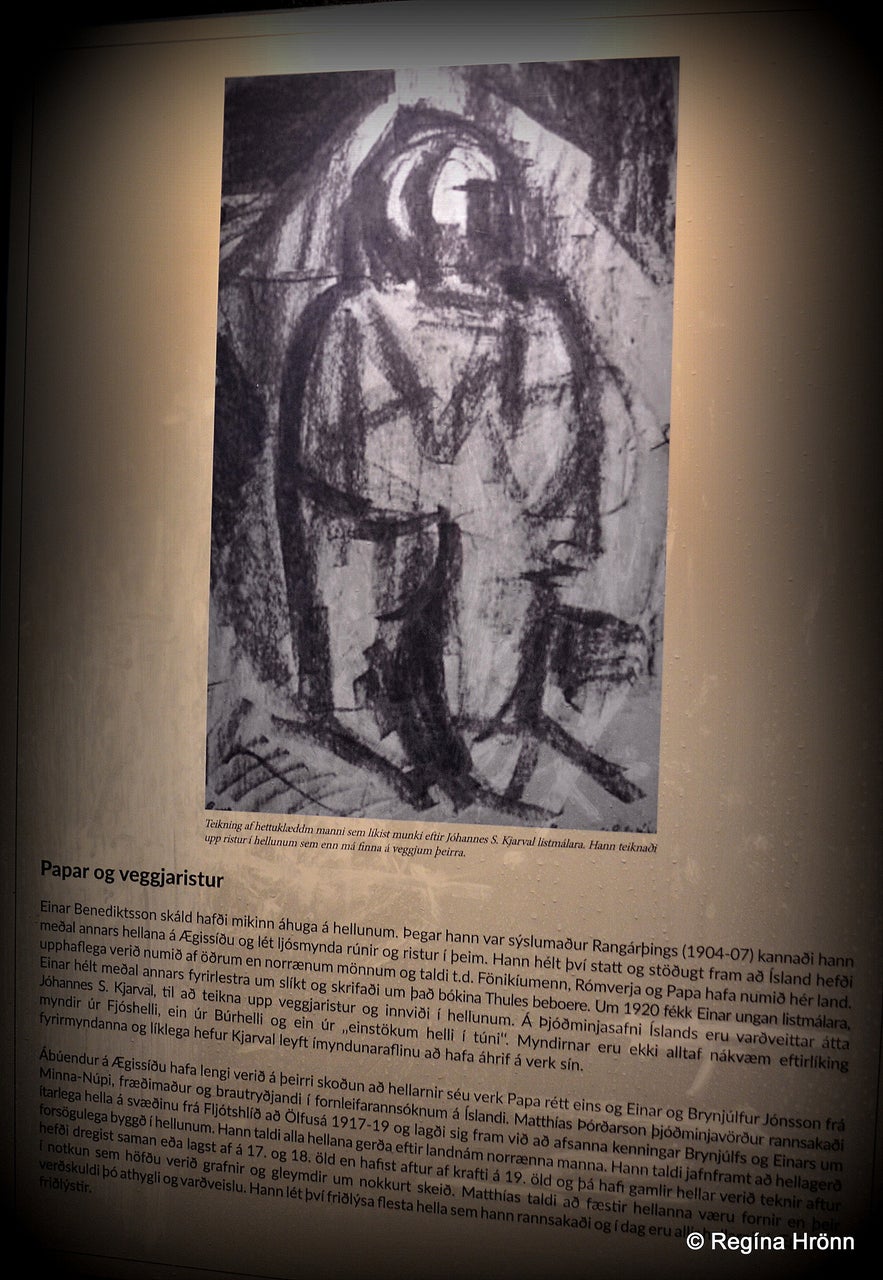

In 1920, Jóhannes Kjarval, who was one of Iceland's best-known painters, accompanied Einar Benediktsson into the caves and made drawings of the engravings in some of the man-made caves in South Iceland.

Out of focus, but are these Ogham engravings?

Out of focus, but are these Ogham engravings?

Kjarval made 11 photographic plates of the Ægissíðuhellar caves, and in one of the caves, you will find information signs with one of his drawings.

The caves have eroded to some extent over the centuries, as livestock habitually rub against the cave walls.

And the heat from the hay can erode the sandstone over time, so the caves have changed from how they initially looked. But all the same, they are in excellent condition, and it is amazing visiting them.

An information sign in the caves depicting one of the drawings of Jóhannes S. Kjarval

An information sign in the caves depicting one of the drawings of Jóhannes S. Kjarval

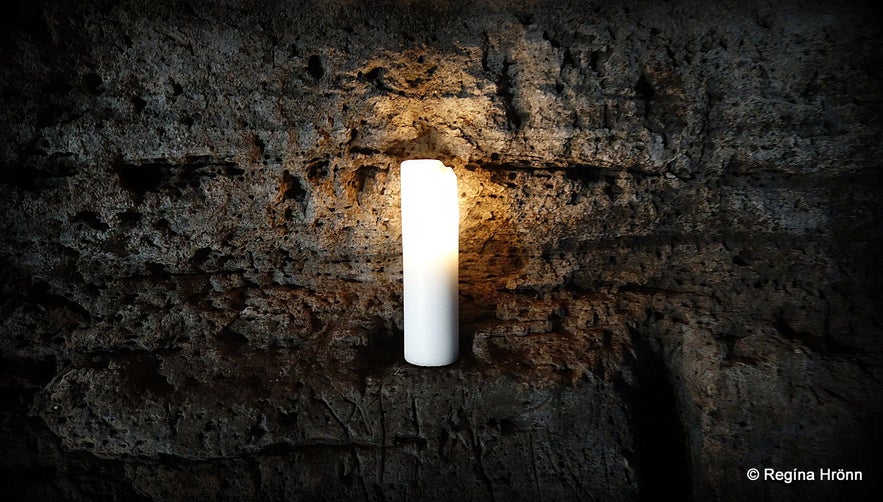

The caves are both haunting and mysterious, and candles add to the mysterious atmosphere. And in some places, you will find carved seats.

The candles are placed on carved torch sconces on the walls, which might have been used to light the cave in these old, forgotten (or kept from us) times.

Were they the place of worship before the Norse settlers arrived? Will we ever find out?

People in the olden days seem to have shunned the caves, and children were told to keep quiet around them and show respect. Why were they afraid of these caves? What happened in the man-made caves?

Engravings on the walls lit up by candles

Engravings on the walls lit up by candles

Did the caves keep some mysteries or secrets? Were they cursed or enchanted? It is a lost history of Iceland that I would love to learn more about.

We have the Sagas that tell us about the settlers of Iceland and their second and third generations, but what about these people? Did they really live here before the Vikings arrived?

The Vikings did not live in caves, but there are stories of Irish monks living in sandstone caves in Ireland, where many man-made caves exist.

So they most likely made these caves before the Vikings arrived. Again, I must reiterate that we are just speculating here.

There is a cross behind me on the cave wall, but it cannot be seen clearly in this photo

There is a cross behind me on the cave wall, but it cannot be seen clearly in this photo

In one of the Icelandic Sagas, Gunnars saga Keldunúpsfífls, it is mentioned that Geir at Geirland at Síða had 10 Irish thralls.

This Saga is believed to have been written in the 14th century about events that are supposed to have happened in the 10th century.

The thrall in charge was Kolur, and it was his task to guard the sheep in the winter and summertime. But he gave the other thralls the task of constructing large caves on Geir's farm for the livestock and hay.

A map with the names and the location of 9 of the Caves at Hella

A map with the names and the location of 9 of the Caves at Hella

I have stayed at Geirland a couple of times, but it is now unknown where these old caves might have been.

This shows that the Irish possessed the know-how for cave building in their country, which the Norwegian settlers might not have had.

And that they might have been ordered to dig these caves for the Vikings. This makes it difficult to determine the age of the caves.

The earliest written source on man-made caves in Iceland is from Jarteinabók Þorláks helga - the Miracle book of St. Thorlak, who was the Bishop of Skálholt from 1178-1193, which his nephew Bishop Páll Jónsson at Skálholt (1195-1211) brought in 1199 to the parliament at Þingvellir.

Fjóshellir cave as seen from the Chapel

We are taught at school from an early age that there were Irish monks here when the Vikings arrived, as this is the only local knowledge we have of other people living in Iceland before the Norse settlement, as foreword in Landnámabók - the Book of Settlements.

The foreword in Landnámabók also states that the holy priest Beda (Saint Bede) mentioned an island called Thile (Thule) in his chronicle.

"It is written in books that it takes 6 days to sail to that island north of Britain, and he said that there is no day in the wintertime and no night in the summertime when the day is the longest. Wise men gather that Iceland was called Thile."

The English monk Beda died in the year 735 AD, more than a hundred years before the Norwegians settled Iceland, the foreword in Landnámabók states.

Crosses and signs on the walls of the caves in Fjóshellir cave

The following paragraph in Landnámabók describes the Irish monks known as the Papar.

In the foreword of Landnámabók, it is written: "But before the Norwegians settled Iceland, here were men, whom the Norwegians call Papar; they were Christian men, and it was thought that they came from the west, as they left Irish books, bells, crosiers, and more items, so it is believed that they were Vestmenn - Westmen.

It is also mentioned in English books that back then, people were sailing between these two countries."

In the olden times, the Norse Vikings called the Gaelic people Vestmenn (Westmen).

One of the old bells at Þjóðminjasafnið - the National Museum of Iceland

One of the old bells at Þjóðminjasafnið - the National Museum of Iceland

Small bells of all kinds were characteristic of the rituals of the Irish church.

And, in at least three pagan graves in Iceland (at Kornsá in Vatnsdalur valley, in Vatnsdalur in Patreksfjörður, and Brú in Biskupstungur), small bronze bells have been found, which might have been Irish bells, might not, but they were used as decorative elements on necklaces.

Old Irish bells in the National Museum of Ireland

Old Irish bells in the National Museum of Ireland

The bell in Vatnsdalur is most likely from the British Isles, where Nordic people lived.

These bells are an interesting find, whatever their origin might be.

Why the Papar left their valuable Christian belongings behind, we don't understand, unless they were driven away or even killed? We are trying to read between the lines here...

The descendants of the Norwegian settlers wrote the story down, so they might be partial in their account, and maybe they did not tell us the whole story.

Ari fróði, the Wise, the father of Icelandic historiography, wrote Íslendingabók, or the Book of Icelanders, which is the early history of the Icelanders.

Ari wrote Íslendingabók in 1122-1132 - the first written work of history in Iceland from the settlement until 1118.

His last sentence in Íslendingabók is: "En hvatki er missagt er í fræðum þessum þá er skylt að hafa það heldur sem sannara reynist" and I have always wondered why he added this sentence at the end.

This sentence, translated into English, means: "If anything proves to be wrong in these writings, then it must be corrected and the truth be told."

Engravings on the cave walls in Fjóshellir cave

The noted Árni Óla states in his book Grúsk (pages 36-37) that the Irish may have arrived at least 150 years before the settlers.

And, in the Mensura orbis terrae, written in 825 by the Irish monk Dicuilius, he mentions Irish hermits who were in Thule some 30 years earlier (795), and that they had marveled at the midnight sun.

He did not mention, though, when the Irish first arrived in Iceland, which might have been earlier than the 8th century.

I stayed behind for a couple of minutes in Fjóshellir to try to sense the spiritual energy of the cave

The Vikings were heathens, believers in the old Norse faith and in Óðinn and Þór. It wasn't until the year 1000 that the Vikings adopted Christianity.

There had been some Christian settlers, though, such as the noted Auður djúpúðga and her siblings, Þórunn hyrna and Helgi bjóla, who settled in Eyjafjörður in North Iceland and Kjalarnes in South Iceland.

The Vikings brought with them enslaved Irish people, who were Christian. Was there a larger Irish population here when the Vikings arrived? This theory is controversial, but not unlikely.

In Hlöðuhellir cave

In Hlöðuhellir cave

There are old stories in Ireland about an Irish population here in Iceland long before the Norwegian Vikings settled it (they were not all Vikings, but I refer to them that way).

Did the Vikings kill them, drive them away, or incorporate them into their settlement?

And how did the Vikings treat their Irish thralls in the Sagas?

In the old Icelandic Sagas, all of which I have read with great enthusiasm, there are many mentions of the Irish thralls.

It always bothers me when I read the Sagas how badly they were treated and how stupid and clumsy they are depicted in many of the Sagas. And they are often referred to as possessing sorcerous powers.

The entrance to one of the caves

The entrance to one of the caves

We Icelanders have no ancient habitations of our forefathers, as Icelanders lived in turf houses that had to be constantly maintained and would collapse if left on their own.

So these caves with all the engravings, the underground habitations (if they were habitations), are of special interest to us.

We have many archaeological sites where the ruins of old Viking houses have been uncovered. Some of the archaeological ruins predate the settlement of Iceland, and some may have been fishing stations.

I have written another travel blog: Ancient Archaeological Viking Ruins and Burial Mounds I have visited on my Travels in Iceland, if you want to see where to find them.

If you want to visit the Caves of Hella, this is the standard tour I joined twice: Caves of Hella Guided Tour | Archaeological Exploration of Iceland's Oldest Man-Made Site.

There are also concerts and happenings in the caves, as there are excellent acoustics, especially in Hlöðuhellir cave, according to Baldur (Bændablaðið). There have even been wedding ceremonies in the caves.

American experts in medieval art history and geology have been examining the caves using advanced technology, and we are eagerly waiting for their results.

In Fjóshellir cave

The Caves of Hella are very accessible as they are right by the Ring Road, right before you reach the river Ytri-Rangá and the village Hella in Rangárþing ytra (given that you are driving in the east direction from Reykjavík).

A big thank you to the cave owners for making them so accessible! Have a lovely time in the Caves of Hella, and enjoy your Iceland visit :)

Ref:

Hellarnir á Hellu - the Caves of Hella

Landnámabók - the foreword

Bændablaðið - Hellarnir við Ægissíðu á Hellu

Grúsk - Árni Óla - pages 31-37

Landnámið fyrir landnám - Árni Óla

Manngerðir hellar á Íslandi pages 144-163

Kuml og haugfé by Kristján Eldjárn - pages 23-25 and 387-389

Gunnars saga Keldunúpsfífls chapter 1

Will American scientists discover the origins of the Caves of Hella?