The Story of Icelandic Cinema

Today, the Icelandic film industry is undergoing a blossoming period; not only does the country distribute four domestic films per year (give or take), but international production companies, such as 20th Century Fox and Lucasfilm Ltd, are now swarming to the country to photograph the science-fiction-esque landscape. Read on to find out more about the story of Icelandic cinema!

- Interested in cinema? See The Top Film Festivals in Iceland

- Learn more about Famous People from Iceland

- Don't miss this amazing Game of Thrones Self Drive Tour

- Or alternatively, Game of Thrones Guided Tour Vacation Package

Such recent productions as Star Wars: Rogue One, Prometheus, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty and many more, have all chosen to stage their shoots here, in part due to the attractive 25% rebate offered to filmmakers shooting in the country.

These are the two crucial factors that have given Iceland’s its fairly recent reputation as an attractive and affordable filming location. Below, you can see a showreel from Truenorth, a production company located in Reykjavik.

This recent attention should do nothing, however, to diminish the homegrown talent, nor the domestic industry, both of which have grown steadily over the last half century.

Before the foundation of a national television station in 1966, Icelandic filmmakers were largely constrained to acting as amateur cameramen, shooting on 16mm film and documenting the natural wonders we are so acquainted with today.

The television station was the first institution where filmmakers could actively and professionally pursue their craft, laying the groundwork for the broadcasting industry to come. That same year, the Association of Filmmakers was formed with the sole purpose to increase technical training and spread the cinematic movement throughout Iceland.

The full story of Icelandic cinema, however, has much deeper roots in history.

- See also: Movie Locations in Iceland

- Check out this interesting Icelandic Mythical Walk

The Early Years

Iceland has been the subject of documentary productions since the beginning of the twentieth century, the oldest of which is still preserved from 1906. The first feature film shot on the island was a Danish film, directed by actor and filmmaker Gunnar Sommerfeldt, called Saga Borgarættarinnar (Sons of the Soil) (1921).

Two years later, a short Charlie Chaplin inspired comedy, The Adventures of Jón and Gvendur, was directed by local photographer, Loftur Gudmundsson, hailing the first thoroughbred Icelandic film. Loftur Gudmundsson would go on to become one of the pioneers of film production in Iceland.

In 1925, Loftur Gudmundsson set about shooting the first documentary focused solely on Iceland. Throughout the previous year, Loftur travelled his country extensively, shooting the landscape and the daily lives of its inhabitants. Fishing villages and herring serve as an important focus throughout these narratives, offering today’s viewers a clear insight into how Iceland operated nationally in the early years of the last century.

The completed film, Ísland í lifandi myndum, was released in 1925. Loftur Gudmundsson would cater much of his later work towards capturing the fishing industry in Iceland, and would also go on to produce two feature films, the first Icelandic ‘talkie’, Milli fjalls og fjöru (1949) and Niðursetningurinn (1951).

The sixties were a relatively quiet time for Icelandic cinema, with only two major productions produced in that decade. These were The GoGo Girl (1962), directed by Eric Balling, and Hagbard and Signe (1967), a co-production between Iceland, Sweden and Denmark. As is often the case with Scandinavian cinema, the film took its inspiration from history, particularly the twelfth-century work Gesta Danorum, by Saxo Grammaticus.

With a renewed interest in cinema throughout the seventies, film clubs and organisations also played their part in the birth of a burgeoning industry. It is indisputable, however, that the main charge for industry growth was led by the visionary ambitions of Iceland’s earliest auteurs, of which no man was more important than Friðrik Þór Friðriksson.

- See also: Literature in Iceland for Beginners

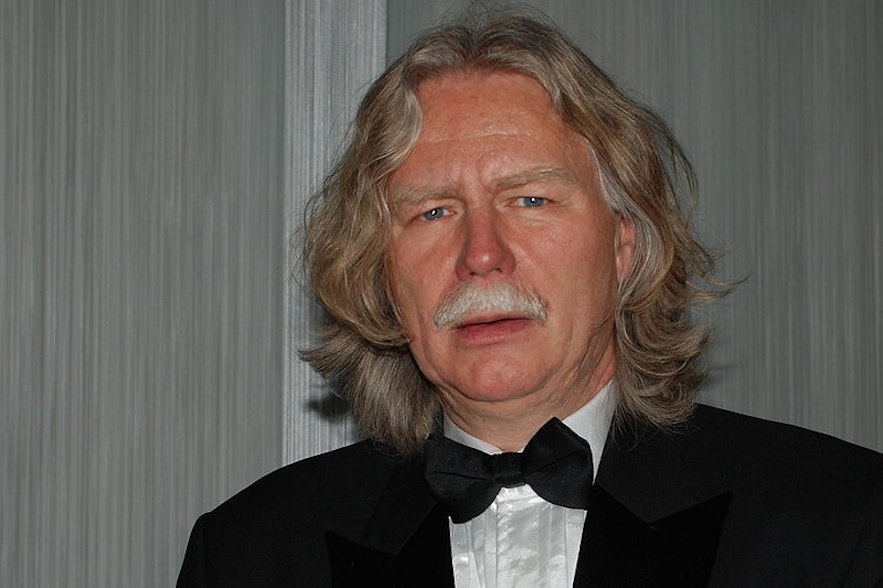

Friðrik Þór Friðriksson

Friðrik Þór Friðriksson is one of Iceland’s more renowned filmmakers; he was oscar nominated for Best Foreign Language Film at the 64th Academy Awards, for his second feature Children of Nature (1991), a feat still unmatched in Icelandic cinema.

He had founded the Icelandic Film Corporation in 1990 as a means of producing his own films, but after the break out success of Children of Nature, the company went through enormous growth, eventually becoming the flag bearer of the Icelandic film industry.

Aside from drawing foreign filmmakers to utilise Iceland’s fantastical scenery for their shoots, Friðrik drew creative partnerships with established film companies abroad, including Lars Von Trier’s Zentropa and Francis Ford Coppola’s American Zoetrope, the studio responsible for such cinematic landmarks as The Godfather (1972) and Apocalypse Now (1979).

As a child, Friðrik absorbed American cinema, though it was largely the work of such legendary directors as Akira Kurosawa and John Ford that pushed him towards the cinematic arts.

Friðrik began his career in the 1980s shooting experimental films and documentaries such as the independently produced Rock in Reykjavik (1982), a bare-faced account of the anarchistic lifestyles of punk rockers and new-wave performers living in Iceland’s then isolated capital.

In 1985, he produced the avant-garde film Hringurinn, which showcased a round trip around Iceland, a snapshot of the journey being captured every 12 seconds with a wide angle lens.

His first feature film was Skytturnar (“White Whales”) (1987), the story of two whalers who, after a night out in Reykjavik, are soon drawn into a violent confrontation with the police.

It was Children of Nature, however - the sad yet sweet story of two elderly characters retreating to the wilderness to die - that put Friðrik on the international stage, simultaneously leading to Iceland’s movie boom in the 1990s.

Throughout the next decade, Friðrik continued to hone his already distinct aesthetic style, challenging himself as a filmmaker to find stories that both explored the human condition and reflected the Icelandic national character.

In 1995, he released the critically acclaimed Cold Fever, a film about a Japanese businessman travelling to Iceland to bury his deceased parents. This was the director's first English language film.

Since the millennium, the director has continued to tread new ground, both personally and professionally, with films such as A Mother’s Courage: Talking Back to Autism (2009) and Mamma Gógó (2010).

His vision and craftsmanship have made him Iceland’s leading directorial voice, driven from a passion best surmised, perhaps, by the man himself; “Filmmaking is the greatest strip-tease of all. You’re always showing your own feelings and ideas.”

Ágúst Guðmundsson

Ágúst Guðmundsson was another forefather of the Icelandic film industry, and is often attributed as having heralded in the ‘spring of Icelandic filmmaking’. This period began with the 1978 founding of the Icelandic Film Fund, a state body designed to provide financial aid for filmmakers across all stages of production.

Already a passionate cinephile - he formed his school’s film appreciation society in the 1960s, and studied directing at the National Film School in London - Ágúst Guðmundsson was the first filmmaker to release a film financed by the Icelandic Film Fund, his directorial debut Land and Sons (1980).

Land and Sons is a hugely important film to Icelanders for a number of reasons. Firstly, the themes the film explores still echoes across the country’s culture today; stoic patriotism, island tradition, the changing faces of a community, the temptations of modern living - all are explored throughout the film’s 90-minute run time.

The film is based on Indriði G. Thorsteinsson’s novel of the same name, set in 1937, in an isolated valley in the north of Iceland. The film follows the relationship between a farmer and his son, both of who value the world differently and significantly, a problem made all the worse in the face of growing property debts.

Whilst the older generation clings to their farm, their district and their way of life, the youth is quick to abandon the struggles of rural living, instead focusing their attention on the possibilities of urban modernity. This generational discrepancy is still felt by many Icelanders today.

The second reason Land and Sons holds such cultural esteem is due to the film’s reception. The Icelandic population came out in droves to purchase tickets upon the film’s opening, with approximately a third of the country (100,000 people) watching it in the cinema. Foreign critics also received the film with praise. Archer Winsten of the New York Post wrote,

‘Watching it I was struck by the horrible contrast with American films that too often trashily cater to the markets of pornographic sex, bloody violence, sci-fi fantasy and nightmare horror that gives kids the creeps. It is a quietly told epic of land and city, of plain people whose concerns avoid all taint of theatricality. It is a noble film, doubtless much too good to be grabbed by commercial exhibitors who have so successfully corrupted all of us.’

The film was shown at the 1980 Chicago International Film Festival and the Taormina Festival in Italy, where it won Silver. The film was selected as the Icelandic applicant for Best Foreign Language Film at the 53rd Academy Awards, but was not chosen for entry (perhaps this had something to do with the movie’s expected notoriety; one scene involves a real depiction of shooting a horse.) Regardless, the world’s eyes had turned to Iceland’s flourishing new industry. Those eyes have not turned away since.

Ágúst Guðmundsson went on to have a prolific filmmaking career. In 1981, he directed the saga-inspired Outlaw: The Saga of Gisli, a film that was met with particularly high praise in both Sweden and West Germany.

He followed this with two domestic comedies, On Top (1982) and Golden Sands (1984), both of which saw theatrical release in Iceland. He also worked on the children’s television series, Nonni and Manni (1988).

In recent years, Ágúst is more widely known for his film The Dance (1998). This story revolves around an Icelandic wedding on the Faroe Islands which quickly turns into chaos when the guests realise a British trawler is sinking nearby.

The film was taken around the festival circuit, screening at Festroia International Film Festival and the 1998 Toronto International Film Festival, finally winning the prizes for Best Cinematography and Best Director at the 21st Moscow International Film Festival.

Upon the production’s domestic release, film critic Guðmundur Ásgeirsson wrote of the picture, "The Dance is the best Icelandic film of the last year and raises hopes of a brighter future for the industry." One of Ágúst’s most recent pictures is Spooks and Spirits (2013), which premiered at the 36th Mill Valley Film Festival in California.

Benedikt Erlingsson

Benedikt Erlingsson is an established theatre director and actor on home soil, but his push into filmmaking over the last fifteen years have left international audiences craving more and more of his cinematic brilliance.

Hross í oss (Of Horses and Men) was Benedikt’s first foray into feature filmmaking, having previously shot two short films, Takk fyrir hjálpið (2007) and Naglinn (2008).

Of Horses and Men is a comedy romance that unravels the human side of horses, and the animal side of people. Starring famed Icelandic actor, Ingvar Sigurdsson, critics pointed to Benedikt’s fantastic eye for photographing the local scenery, and soon it was a darling of the festival circuit, winning such awards as the New Directors Prize in San Sebastian and the Nordic Council Film Prize.

Before embarking on the film that would make him internationally renowned, Benedikt directed the documentary The Show of Shows (2015). With a moody score developed by the members of Sigur Rós, this non-narrative documentary expertly showcases old circus footage—tightrope walkers, acrobats, clowns, dancers, etc.—but also reveals the darker nature of show business, particularly its torturous use of performance animals.

Kona fer í stríð, better known to English-speaking audiences as ‘Woman at War’, is Benedikt’s breakthrough film. The film follows Halla—masterfully portrayed by Halldóra Geirhardsdottir—an environmentalist who chooses to disrupt Iceland’s harmful infrastructure with a makeshift bow and arrow.

Government officials, hellbent on a smear campaign, label her an eco-terrorist, while others prefer the term eco-warrior.

Woman at War forces the audience to contemplate their own actions in relation to nature and their environment. It also manages to settle its characters in realism; one of the most poignant arcs is Halla’s attempts to adopt, pushing the notion that saving the earth begins at ground level, in this case saving one child.

Hrafn Gunnlaugsson

‘The most dangerous people you have when you are making a movie is people with good ideas because they are making another movie. They are not making what’s in your head. So the one thing is when you make a movie, you have to concentrate, see the light at the end of the tunnel and you need to go there. Never listen to people with good ideas and never forget what you saw in the beginning. That is the only way to succeed.’

This quote is from the legendary director Hrafn Gunnlaugsson, summing up the auteurs’ filmmaking method almost perfectly. His expertise can hardly be questioned, after all, having directed around 18 films and hailing from a family of artists.

His sister is the actress Tinna Gunnlaugsdóttir, a star of many domestic films in Iceland, whilst his son Kristján is a playwright and poet and his daughter Tinna pursues acting, having performed in The Quiet Storm (2007) by Guðný Halldórsdóttir.

Throughout the seventies, Hrafn mastered his craft working on television for the domestic market, both on TV movies and series. His first feature film, a comedy-drama called Inter Nos (1982) examined the mid-life crisis of the story's central protagonist, an engineer called Benjamin Eiriksson who is desperate for a fresh start in life.

However, it was not until the director’s perceived masterpiece, the Viking epic When the Raven Flies (1984), that Hrafn Gunnlaugsson truly made a name for himself as one of Iceland’s premier filmmakers.

From the outset, When the Raven Flies appears to be a traditional tale of vengeance, focusing on the Irish hero Gestur questing to kill the Viking murderers of his parents. However, on watching the film, there are clear influences one would not expect within the world of Norse mythology.

The camera’s energy and quick-cut editing are reminiscent of Sergio Leone’s ‘Spaghetti Western’ genre, whilst the film’s main characters and plot allude heavily to the 1961 Japanese film Yojimbo, directed by Akira Kurosawa. For his part, Hrafn Gunnlaugsson won the 1985 Guldbagge Award for Best Director.

When the Raven Flies was the first film in the Viking Trilogy (otherwise referred to as “the Cod Westerns”), followed by In the Shadow of the Raven (1987) and The White Viking (1991), the last of which was also edited into a mini-series.

This trilogy was almost compulsory viewing for a generation of Icelanders who soaked up the true-to-life incarnation of their Viking heritage. One particular scene, often referred to as the fertility game, demonstrates Hrafn’s auteurism acutely. Be warned, the scene is in many ways quite graphic.

Since his historical trilogy, Hrafn has continued to direct films for the domestic market. His last film, A Revelation for Hannes (2004) was a technological drama set around the immoral collection of personal data.

The film caused quite a stir upon its release, and is even said to be one of the motivating factors that led Icelandic banks toward privatisation. This is further proof of the strengthening influence of Iceland's film industry.

Hrafn’s down to earth yet eccentric style has affected both the director’s films, art and personal philosophy. Nowhere is this more apparent than the director’s home, a raven’s nest of playful and eclectic decorations ranging from twisted iron sculptures to large stones, collected from around the country. Hrafn also keeps a personal cinema in his home where he regularly invites guests and exhibits his films.

Baltasar Kormákur

Today, it is Baltasar Kormákur at the forefront of the Icelandic film industry, having directed both homegrown classic such as 101 Reykjavik (2000) and The Sea (2002), as well as Hollywood spectacles such as the 3D IMAX film Everest (2015).

Originally one of Iceland’s most well-known screen actors, Baltasar chose to focus his creative attention behind the camera, a decision he made after deploring his own performance in his directorial debut 101 Reykjavik. Thankfully, this proved to be a wise career decision; Baltasar was the forerunner for Icelandic filmmakers looking to make their mark in Hollywood.

101 Reykjavik is an important film in Icelandic culture - the first Icelandic film of the 21st Century - and is one the most recognisable productions to international audiences, in good part due to its score, composed by Blur frontman, Damon Albarn.

The film manages to perfectly capture the urban life of its central character, 101-rat Hlynur, an apathetic thirty-year-old whose isolated lifestyle somehow mirrors that of his home country.

Played superbly by beloved Icelandic actor, Hilmir Snær Guðnason, Hlynur’s quiet life is turned upside down upon the realisation that his mother is not only a newly declared lesbian but is also madly in love with Lola, a Spanish flamenco instructor and (to make it more complicated) the casual lover of Hlynur.

101 Reykjavikis often cited as the finale in an unofficial trilogy of Icelandic films that use Reykjavik’s downtown as their primary focus, the other two being Rock for Reykjavik (1982) and Óskar Jónasson’s action-comedy, Sódóma Reykjavík (“Remote Control”) (1992).

For 101 Reykjavik, Baltasar won the Discovery Award at the 2000 Toronto International Film Festival, amongst a flurry of other nominations. Critics noted its confident stylistic choices and cultural grounding, marking Baltasar Kormákur as a director to watch out for.

He followed his directorial debut with the film The Sea (2002), the story of a wealthy yet troubled Icelandic family living in a small coastal town. This too was met with high praise, winning eight prizes at the 2002 Edda Awards.

After a string of Icelandic films, Baltasar worked primarily with Hollywood producers, shooting the action-packed blockbusters Contraband (2012) and 2 Guns (2013), both of which starred actor Mark Wahlberg in a leading role. In 2014, Baltasar took his film crew to Italy, Iceland and Nepal, all to shoot the biographical film Everest, a story based on the 1996 Mount. Everest disaster. The film starred Keira Knightley, Josh Brolin and Jake Gyllenhaal.

In 2015, the film had a wide theatrical release and was shown in IMAX 3D in select cinemas, earning positive reviews from the critics and grossing an incredible $43,482,270 by the year’s end.

In 2016, Baltasar Kormákur purchased 20,000 square metres of property outside of Reykjavik, a space he intends to become the hub of cinematic production in Iceland.

Speaking at the Reykjavik Film Festival last year following a screening of Everest, Baltasar described the site as “ a film village, but it’s also the beginning of a creative village, a village of creative industries for Reykjavik.” The area will be developed and made operational in 2017, setting the stage for Baltasar’s highly anticipated, and as of yet unnamed, Viking epic.

In 2018, Baltasar Kormákur directed the romantic drama, Adrift, telling the story of a young couple in love, sailing at sea in one another's company, before fighting for their lives against an enormous storm. The film review website, Rotten Tomatoes, marks the film at 73% approval rating.

Guðný Halldórsdóttir

Guðný Halldórsdóttir, the daughter of acclaimed author Halldor Laxness, is something of a rarity in the Icelandic film industry, only in so much that she is a female director.

Despite Iceland’s excellent international reputation for gender equality, the role of women is severely lacking when it comes to the production of films. The statistics in this area, unfortunately, don’t lie. In 2016, only 7% of Icelandic films were directed by women. There was only minor progress on the writing, with 16% of screenplays by women. Perhaps most obviously of all, 71% of all main characters were men.

- See also: Top 9 Famous Icelanders in History and Gender Equality in Iceland

Guðný began her career studying filmmaking at the London International Film School, graduating in 1981. Her first major step into the industry came following the sale of her script, Stella on Holiday (1986), directed by fellow female filmmaker, and later member of the Alþingi, Þórhildur Þorleifsdóttir.

Her own directorial debut came in the form of Under The Glacier (1989), an adaptation of her father’s 1968 novel of the same name. Three years later, she directed the black comedy The Men’s Choir (1992), a vengeance tale following a retired actor set to hunt down his father’s murderers.

Guðný continued the trend of adapting her father’s literary endeavours to celluloid, shooting the vampire film Honour of the House (1999). The movie was Iceland’s Best Foreign Language Film submission to the 72nd Academy of Awards, but was unfortunately not shortlisted. Instead, it took the prize for Film of the Year at the first Edda Awards in 1999, an accolade presented by the Icelandic Film & Television Academy.

In 2003, she wrote and directed the sequel to Stella on Holiday, and in 2007 directed the film The Quiet Storm, a tale of a young pianist who, in 1970s Iceland, breaks away from her bourgeois home to live in a juvenile delinquents centre.

Sólveig Anspach

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Anna Rouker. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Anna Rouker. No edits made.

Sólveig Anspach also deserves a place in the history of Icelandic film, despite the fact that she spent most of her working life in France. Born to an American father and an Icelandic mother, Sólveig studied clinical psychology and philosophy in Paris, before enrolling in La Fémis, the state-run film and television school in France. She left with a diploma in directing in 1989.

A year after her graduation, Sólveig returned to the place of her birth for the short documentary, Les Îles Vestmannaeyar (1990), where she shot and explored the beauty and heritage of the Westman Islands.

In 2013, Sólveig Anspach directed the film Stormy Weather, a drama that focuses on the relationship between a French psychiatrist and a mentally-ill Icelandic woman named Lola. This film was the first time that Sólveig worked with poet and actress Didda Jónsdóttir.

Didda would go on to act under Sólveig’s direction in four films and is most well-known for her performances in the Anspach trilogy; Back Soon (2008), Queen of Montreuil (2011) and The Aquatic Effect (2016).

In August 2015, Sólveig died after a long battle with breast cancer. In 2017, numerous institutions in Iceland, including the French Embassy, Reykjavik City Council and the Icelandic Film Centre, organised a short film competition in tribute to the life and work of the director. The competition was solely directed toward female filmmakers, and made up part of the French Film Festival, organised annually in Iceland.

Solveig struggled with her health throughout her career, using the pain and experience in her fiction to add a truly personal depth to the narrative. Nowhere is this more apparent than in her film Haut les Couers! (1999), a French film based on her own experiences being diagnosed with cancer.

When asked in 2014 what spurred her frantic work ethic by french magazine Le Monde, she replied "What drives me forward? Maybe that I know like everyone else that life can end suddenly. I think I simply think more about it than others."

Dagur Kári

Most Icelanders will know Dagur Kári as the director of cult-classic Noi the Albino (2003), a film about a strange, bald-headed loner living without purpose in an isolated fishing town in the west of Iceland.

However, over recent years, Dagur has outshone his contemporaries as one of Iceland’s freshest and most daring filmmakers, taking on projects at home and abroad that almost always derive a level of international attention.

Dagur began his career studying filmmaking at the National Film School of Denmark. His art-house graduation film Lost Weekend (1999) earned him a staggering eleven international prizes, a feat he soon followed by directing one of five segments in the Icelandic compilation film, Dramarama (2001). Dramarama was nominated at the Edda Awards that year for Best Film, garnering the filmmaker a reputation as one of Iceland’s most promising young directors.

Still, it was something of a surprise when Noi the Albino, his next project, received the incredible acclaim it did, not just from home but internationally. Critics were more than impressed with how the film balanced absurd surrealism and light-hearted comedy within a poignant, powerful coming of age story.

They were also quick to note the awe-inspiring visuals - fantastic wide shots of the Westfjords' snowy and majestic landscape - as well as Tómas Lemarquis’ committed portrayal as the titular outsider Noi, an acting challenge that is both breathtaking to watch and, at times, difficult to bare.

This is testament to one of the film’s only professional actors, the rest of the cast being made up of relative unknowns. The director also utilised his own band, Snowblow, to score the production, underlying the film with a moody and often haunting soundtrack.

Since Noi the Albino, Dagur has continued to find success. In 2005, he released the Danish film, Dark Horse, which later premiered at the Un Certain Regard section of the Cannes Film Festival that year.

His first English language feature, The Good Heart (2009) starred acclaimed actors Paul Dano and Brian Cox, making its debut at that year’s Toronto International Film Festival.

In 2015, Dagur returned to Iceland to shoot the film Virgin Mountain, starring Gunnar Jónsson. The film tells the story of a middle-aged Icelander struggling to break out of his daily routines.

Living with his mother, the central protagonist spends his days working as ground staff at the airport or creating miniature battlefields at home. All of that changes, however, when he falls in love after having been reluctantly enrolled in an amateur dance class.

Virgin Mountain was met with a much higher level of acclaim than Dagur’s last film, winning prizes for best narrative feature, screenplay and actor at the 2015 Tribeca Film Festival. In the same year, the film also won the Nordic Council Film Prize.

As of 2015, Dagur Kári works as the Head of the Director’s program at the National Film School of Denmark.

Cinemas & Film Festivals

Photo from Bíó Paradís

Photo from Bíó Paradís

Bíó Paradís (“Cinema Paradise”) is an independent Art House cinema in downtown Reykjavik, the only one of its kind in Iceland. Since 2010, the cinema has focused its screening towards the latest experimental releases, be they Icelandic or international productions.

The cinema has four screens of different sizes, the largest of which can accommodate 205 people. They also serve traditional popcorn and snacks at the confectionary, and for the added luxury, house a bar, making it possible to sit and enjoy a refreshing pint whilst watching the latest features.

Bíó Paradís is the only cinema in Iceland that still screens Icelandic short films and documentaries, making it a cultural gem for those devoted to watching the development of Iceland’s film industry. Given this fact, the cinema engages Icelandic school children in educational programs in order to spread how important the art truly is.

Photo from Bíó Paradís

Photo from Bíó Paradís

The cinema is the gathering point for numerous festivals that are held in Reykjavik throughout the year. The most important is Reykjavik International Film Festival, an event that lasts for eleven days, focuses on emerging talent and distributes filmmaking awards, most notably the Discovery of the Year Award, otherwise referred to as the Golden Puffin.

The festival was conceived of in 2004 by a group of cinema enthusiasts looking to not only boost the film culture of Iceland but also to draw an international crowd. Now in its thirteenth year, the founders can be proud of the fact that RIFF not only excels as an alternative film festival in Europe but is also one of the more dominant portals from which new films can gain exposure.

Stockfish Film Festivalalso uses Bíó Paradís as its main exhibition hub. This particular festival is a 2015 reincarnation of the Reykjavik Film Festival, which was originally established in 1978. Like RIFF, the festival lasts for eleven days with its main purpose being the building of bridges between filmmakers in the international community.

Every year, the festival invites guest speakers to discuss the state of international filmmaking, and runs to specialised sections; the Shortfish competition (dedicated, quite obviously, to short films by Icelanders) and Works in Progress, a unique chance for members of the public and the media to get an insider’s view into the current projects being worked on by filmmakers from across the world.

Other festivals that take place at the cinema include Stockfish Reykjavik Shorts & Docs Festival and Reykjavik Short Film Days, both of which are aimed more directly at amateur filmmakers, offering the chance for prospective directors to break through into the industry.

Special Mentions

The Icelandic Film Industry is where it is today due to the grand efforts of far too many people to mention in one solitary article. Below are some other individuals who have definitively made their mark on Icelandic cinema.

-

Sigurjon Sighvatsson is an Icelandic Hollywood producer and businessman. Originally a musician in his native country, Sigurjon left Iceland to study an MFA in Film Studies at the University of Southern California. Since then, he has never looked back.

-

Now chairman of the Scandinavian distribution company Scanbox Entertainment, as well as the principle of Palomar Films, Sigurjon has over fifty film and television credits to his name. Such recent productions produced by Sigurjon include Valhalla Rising (2009), the star-studded Brothers (2009) and the action-packed Killer Elite (2011), starring Jason Statham, Clive Owen and Robert De Niro.

-

Ragnar Bragason is an Icelandic film director who is best known for his companion films Children (2005) and Parents (2007), both of which do away with the tourist-friendly image of Reykjavik, instead delving into the lives those living in a gritty incarnation of Breiðholt suburb.

-

Both films won Edda Awards, a nomination he has received seventy-one times as a director (and won an incredible thirty-two.) In 2012, Ragnar focused his attentions on writing and directing for Reykjavik City Theatre, before returning to the big screen for the Icelandic rock drama Metalhead (2013).

-

Grímur Hákonarson first made a name for himself in 2010, with the release of his debut film Summerland, a film that was immediately nominated for an Edda Award. His next major project was the documentary A Pure Heart (2012), a film that focused on the life of a Selfoss priest still struggling with his own personal demons.

-

Most recently, Grímur wrote and directed the feature film Rams (2015), the story of two disconnected brothers who must come together to deal with an illness spreading between their flocks of sheep. The film was picked to premiere in the Un Certain Regard section of the 2015 Cannes Film Festival.

-

Kristín Jóhannesdóttir is an Icelandic film director and writer best known for her film As in Heaven (1992), the story of a highly imaginative young girl trying to make sense of her life in 1936 rural Iceland.

-

The film was first screened out of competition at the 1992 Cannes Film Festival, and was nominated as Iceland’s entry for Best Foreign Language Film at that year’s Oscars ceremony, even though it was not picked. Kristín’s most recent film is Alma (2017). The story follows twenty-eight-year-old Alma, a woman incorrectly held in a psyche ward for the apparent murder of her boyfriend. When she discovers that her boyfriend is still alive, she decides to murder him after all.

-

Eva Sigurðardóttir is an Icelandic film director and producer who runs the production company Askja Films, an organisation that focuses on the fiction and documentary work of female filmmakers.

-

Her credits have included the BAFTA nominated Good Night (2013), the tale of a woman’s 29th birthday party and how it spirals out of control after she lets her guests in on a deathly secret. Most recently, Eva produced the film Rams (2015).

Andre interessante artikler

Jul på Island | Din ultimate guide til juletradisjoner, mat og mer!

Lær alt om julen på Island. Hva er de viktigste juletradisjonene på Island? Hvorfor har Island 13 julenisser, og er de den samme julenissen? Hvordan feires julen på Island? Hvordan ser julen ut i Re...Les merNyttårsaften på Island

Hvordan er nyttårsaften på Island? Hvordan er nyttårsaften i Reykjavik? Hva gjør nyttår på Island spesielt? Hvor er de beste festene i Reykjavik på nyttårsaften? Lær alt dette og mer i vår komplette g...Les mer

De islandske julekarene og Gryla | Islands juletroll

Hvem er de islandske julekarene? Hvem feires på Island i julen om ikke julenissen? Hvilken rolle spiller kjempen Gryla i islandsk julefolklore, og hva var julekatten? Fortsett å lese for å lære om G...Les mer

Last ned Islands største reisemarkedsplass på telefonen din for å administrere hele reisen på ett sted

Skann denne QR-koden med telefonen din og trykk på lenken som vises, for å legge til Islands største reisemarkedsplass. Legg til telefonnummeret ditt eller e-postadressen din for å motta SMS eller e-post med nedlastingslenken.