The Icelandic Horse | A Comprehensive Guide

What attributes make the Icelandic horse so loved by its people? How different are Icelandic horses from other breeds? Where do you go horse riding in Iceland? Should it be called the Icelandic pony instead of a horse? Read on to find out everything you ever wanted to know about this magnificent animal, from its history since the Age of Settlement, to its significance and status in Iceland today.

The Icelandic horse is as local to this volcanic land as its people. It arrived here on the very first ships of the settlers and has, ever since, remained a loyal friend and vital servant.

The horse, therefore, holds a very special place in the people's hearts and souls, and if you ever have the honour of meeting a member of its species, you'll immediately understand why. Notably more curious, intelligent and independent than other horse breeds, the Icelandic horse is loved by all.

Photo from Classic 11 Hour Golden Circle & Horse Riding Tour with an Audio Guide and Transfer from Reykjavik

Photo from Classic 11 Hour Golden Circle & Horse Riding Tour with an Audio Guide and Transfer from Reykjavik

In this article, we have gathered essential information on this magnificent animal and explored the breed's history and unique traits; its special relationship with the people of Iceland; and its bountiful connotations in regards to the nation's mythology, culture and literature.

Interacting with Icelandic Horses

You will spot Icelandic horses by the side of the Ring Road throughout the country, in all but the worst of weather; they are well used to Iceland's winters. In such situations, it is important that you follow a few simple rules:

- Do not pet the horses: they may bite or kick if you pet them, and are likely to learn obnoxious behaviour that will undo expensive horse-training and later hinder a rider.

- Never feed the horses: they have plenty of food, and any additional treats would only be hazardous to their health.

- Never trespass onto private property to see Icelandic horses: almost all Icelandic horses are kept on private land.

- Never ride a horse without the owner's express permission: this will put you and the horse in serious danger.

- When driving, do not stop suddenly, park in a dangerous spot, park in poor visibility, park on icy roads or park on private property to see Icelandic horses.

If you want to photograph Icelandic horses, ensure you park your car legally in a place that is clearly visible to other road users. If you want to get up close and personal with these animals you need permission from the landowner, or you could simply book a horseback riding tour.

The History of the Icelandic Horse

The very first members of the breed arrived aboard the Viking ships of Norse settlers sometime between 860 and 935 AD. Although sources don't agree on the breed's exact ancestry, interestingly enough, many of its characteristics can be related to the mere circumstances of this transportation.

Some claim that the animals were chosen because of their short but sturdy stature, which made them ideal for overseas travelling. When you think about it, it is much easier to transport larger animals across the roaring ocean if they keep their footing and take up less space on the boat.

- See also: Where Did Icelanders Come From?

- See also: The History of Iceland

Since then, selective breeding has made the Icelandic horse what it is today. It has also changed and adapted to its surroundings, seasonally sporting a thick winter coat which it then sheds come springtime.

The horse is subsequently undaunted by high winds and snowstorms and capable of feats like wading glacial rivers and crossing rough terrains.

In 982 AD, the Icelandic parliament Alþingi passed laws that prohibited any importation of other horse breeds into the country, meaning that for over a thousand years, the breed has been kept in complete isolation within the island.

Consequently, it is one of the purest horse breeds in the world. Although individual animals may be exported, once gone, they may never return.

About 900 years ago, there were attempts to introduce eastern stock into the Icelandic blood, but this experiment resulted in significant degeneration and came close to wiping out the species.

Great care has since been put into protecting the stock, and as a result, it is exceptionally healthy and long-lived. The average animal might live for up to 40 years, with the oldest reportedly reaching the ripe old age of 59.

The horse's physical excellence is far from the only reason why it's so adored by the Icelandic people. The personality of Icelandic horses is also widely celebrated; their spirited but gentle temperament in particular.

Because these creatures have never had any predators in their natural environment, they are not easily spooked, making them very approachable and friendly.

What are the Specific Traits of Icelandic Horses?

One of the Icelandic horse's most notable attributes is its five gaits. Other equine species typically possess the three general gaits of walk, trot and canter/gallop, while the Icelandic horse possesses the two additional gaits of 'tölt' and 'skeið', or 'flying pace'. Each individual animal's ability to perform these two gaits well largely defines its value.

What are those gates? How do they function? And perhaps more importantly: how do they feel? The 'tölt' is a four-beat lateral ambling gait, known for its merger of speed and exceptional riding comfort, so imagine a smooth-as-silk trot as you glide speedily forward.

The 'skeið,' however, could be described as a very rhythmic gallop, a two-beat lateral gait where each side of the horse's feet moves simultaneously, with a moment of suspension between footfalls. At up to 48 km/h (30 m/h), this brisk gate truly feels like flying.

- See also: Volcanic Landscape Horse Riding Tour

The Icelandic horse comes in a rainbow variety of colours, with more than forty basic colourings officially listed, as well as over a hundred variations. Additionally, the Icelandic people have long since believed that a horse's colour might reflect its personality.

An example of this is to be found in one of the adventures of local author Jón Sveinsson's beloved literary brothers Nonni and Manni. The two young mischief-makers are warned against borrowing a nearby farmer's pink horse―since pink horses are said to be willful and hard to break. And sure enough, the brothers lose control of their borrowed steed, and it runs uncontrollably into the wilderness.

- See also: Icelandic Literature for Beginners

This might be the time to address the pink pony in the room: Is the animal a pony, or is it a horse? Our advice to you, right now, is to never ask an Icelandic person that question, ever.

...but since we're on the subject, by definition, ponies are smaller (under 144 cm) and stockier than horses, with a thicker mane, coat and tail. Although the Icelandic horse might, in some cases, fit that bill, locals will always argue, in length and detail, that the Icelandic animal has the genetic makeup, intelligence and strength of a horse.

You can't argue with that. Just don't. So let's move on.

The Icelandic Horse in Mythology and Folklore

Picture by Jakob Sigurðsson from Wiki Creative Commons. No edits made,

The national pride Icelanders take in their horse breed dates back to ancient times. The horse has long been celebrated in Norse folklore, and when the settlers imported the animal, they also imported its mythos.

Literature, poetry and folklore are littered with examples that reflect the nation's admiration of the horse, which throughout history has not only been lauded for being man's most valuable servant, but also his friend and trusted companion.

- See also: Folklore in Iceland

Picture by Oscar Wergeland from Wikimedia Creative Commons. No edits made.

According to Grágás, the first Icelandic book of laws, stealing someone's horse was punishable by banishment and convicted horse thieves were outlawed. During the Viking Age in Iceland, all outlaws could be legally killed on sight, which is telling of the fact that you simply don't steal someone's horse.

The burial customs of the Vikings entailed burying the dead with their personal belongings, with so-called grave goods one might need on their journey to the next world. The higher your rank in society, the more valuable possessions you were able to bring.

It was, therefore, the likes of kings and powerful chieftains that got to have their horse buried with them. For what better companion could you ask for on your trip through the underworld, than your trusted steed?

Picture by W.G. Collingwood from Wiki Creative Commons. No edits made.

In Norse mythology, the most revered of all the gods, Odin, possesses a trusty steed called Sleipnir―an eight-legged creature with the ability to fly, dubbed the finest of all the world's horses.

According to local folklore, Sleipnir is credited with the creation of Ásbyrgi canyon in North Iceland. As the king of horses stepped one of his eight legs down from the heavens and onto the ground, his hoof allegedly left behind the horseshoe-shaped canyon so many travellers visit today for its stunning nature and incredible allure.

The horse who fathered Sleipnir, named Svaðilfari, is said to have helped a villainous giant build the wall of Asgard on a wager against the gods. In fear of losing the bet, the shape-shifting trickster god Loki, in the form of a mare, enticed Svaðilfari away from his master, making it impossible for the wall to be finished before the set time.

The romantic encounter that followed resulted in Loki getting pregnant and soon after, the great god of mischief gave birth to Sleipnir himself.

Many believe this tale to encapsulate how essential the horse was to the human workforce, and how helpless the people would have been without it.

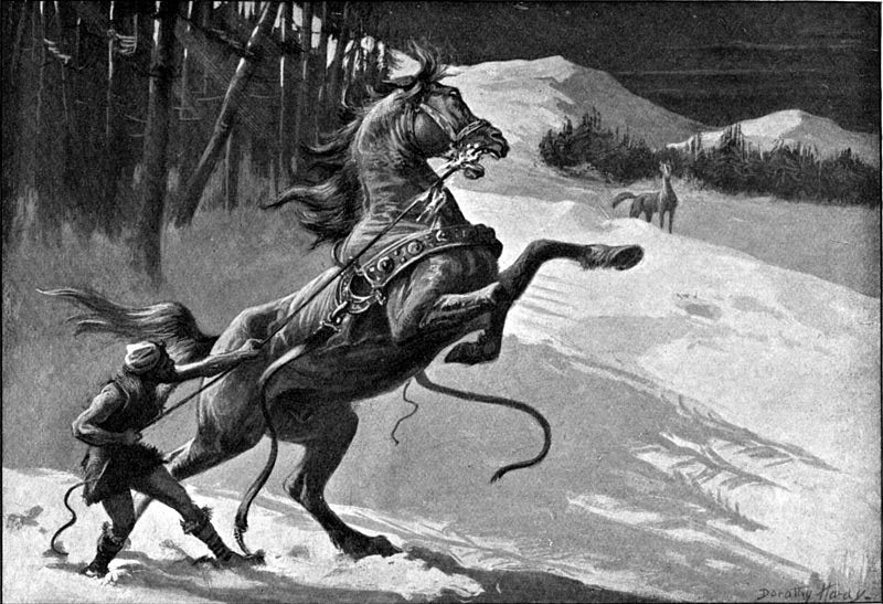

Picture by Dorothy Hardy from Wiki Creative Commons. No edits made.

There is also a repeated motif in Norse mythology involving horses pulling the sun across the sky. In Gylfaginning, the first part of Snorri Sturluson's Prose Edda, the sun is dragged across the heavens on a carriage by two horses called Árvakur and Alsvinnur. Their names roughly translate to 'always awake' and 'eternal victory'.

The horses of deities Dagur (Day) and Nótt (Night) are Skinfaxi and Hrímfaxi, their names translating to 'mane of light' and 'mane of frost'. In pulling Dagur's chariot every day, Skinfaxi's mane and tail lit up the sky and the earth below it. As the sun is the source of life, the horse is then the ultimate bringer of light and fertility.

Picture by John Charles Dollman from Wiki Creative Commons. No edits made.

But not all mythological horses come bearing the sun, for let us remember that the horse is not naturally a servant, but a starkly individual and unpredictable animal. Whether from misbehaving, getting spooked or it being the fault of the rider, a horse can always throw its horseman.

One of the monsters of Icelandic folklore, the Nykur, was a water-demon with the appearance of a horse, except that its ears and hooves faced backwards. The Nykur was believed to reside underwater in lakes and rivers, and its purpose was to pose as a regular horse and lure unsuspecting wanderers to a watery grave.

When the ice cracked on frozen lakes in winter, the noise it generated was said to be the Nykur neighing. This belief, if nothing else, encouraged riders to take great care when crossing frozen waters.

Picture by Theodor Kittelsen from Wiki Creative Commons. No edits make

If you, by any chance, find yourself unlucky enough to be riding a Nykur, there are ways to fending off this devious beast. One is to draw the sign of a cross on its back, and another is to speak its name.

One particular tale tells of a Nykur dragging a sleeping girl into a lake to drown her, until the girl woke and screamed out the creature's name. The demon horse dropped its prey at once and disappeared back into the depths from which it came.

- See also: Witchcraft and Sorcery in Iceland

In fact, the names of Icelandic horses hold an entire tradition of their own. Some refer to their colour, like Bleikur (the pink), Gráni (the grey) and Kolfaxi (black-maned).

Others refer to their temperament or personality, like Farfús (likes to travel), Háski (daredevil), Ljúfur (dear) or Prakkari (trickster). Many names furthermore derive from Norse mythology; for example, Loki, Mjölnir, Ýmir, Þór or Frigg.

You might have heard of the Icelandic Naming Committee, an organisation that maintains the official register of human names in Iceland. Essentially, the committee is one of the vanguards of the protection of the Icelandic language, governing both the upkeeping and introduction of given names in Iceland.

What you might not know, however, is that in Iceland, horses have their very own naming committee, meaning you can't name your horse Cupcake or Harry Trotter like any old pet. It might seem strange, but in reality, the practice reflects the great respect the Icelandic nation has for its valuable companion.

- See also: The 10 Weirdest Things About Icelanders

It is also a commonly held belief that you should never ride a horse whose name you don't know or understand. So before embarking on a horse riding tour, if you want to ride like a local, remember to ask your guide about the name of your companion animal, as well as the meaning of said name.

Of Horses and Men

In the past, the horse was absolutely necessary to the survival of the Icelandic people; it was their best and surest way of transportation and often, quite literally, a lifesaver. Many tales tell of riders getting lost in blizzards in Iceland's unforgiving wilderness, where their horse kept them warm until rescued or simply found its own way home, carrying the exhausted rider back to safety.

Today the mechanisation of transport and general road improvements have greatly reduced the need for the horse, but it still plays a significant role in the lives of the Icelandic people.

Farmers still use horses for sheep-herding in the Highlands, people keep them for leisure riding, and popular competitions for gait performance, racing and showmanship have been held annually since the late 1800s.

It may also be obligatory to inform you that, yes, Icelanders do eat horse meat and some horses are, like most of the world's farm animals, bred solely for human consumption. Many people stay away from it, while others don't see the difference in eating horse, lamb, beef or pork.

- See also: Top 21 Vegan & Vegetarian Restaurants in Reykjavik

Many outsiders are shocked at the thought of eating horse (remember that incident in the UK?), but the practice wasn't always a clear-cut case in Iceland either.

After the Christening of the entire country in the 10th century, eating horse-meat was, in fact, forbidden. The few poor souls who did were disgraced, and on average, people would rather have starved than risk damnation for eating horse meat.

In today's Iceland, the horse is much more generally considered a friend and a comrade. Many Icelandic children attend riding classes held both outside and within city limits, and with the great boom in tourism in recent years, demand for well-bred horses for riding has never been higher.

A traveller might be said not to have fully experienced the beauty of the Icelandic nature without having witnessed it from a horse's back.

Horse riding gives you a chance to get off the roads, while still braving up mountains and wading across glacial rivers. It means flying through the Icelandic scenery and exploring the land in the same way as the settlers did, and their descendants have kept on doing ever since.

When coming to Iceland to meet the Icelandic horse, know that you will have encountered a unique and exceptional animal. Treat them as such, and we're sure you'll get along just fine.

Muita kiinnostavia artikkeleja

18 käyntikohdetta ja nähtävyyttä Islannissa

Löydä täältä Islannin parhaat tärpit ja lue, mitkä ovat Islannin suosituimmat käyntikohteet ja nähtävyydet. Etsitpä sitten luonnonihmeitä, kulttuurielämyksiä tai Islannin kätkettyjä helmiä, lue arti...Lue lisääTäydellinen opas keskiyön auringosta nauttimiseen Islannissa

Opi kaikki mitä sinun tarvitsee tietää keskiyön auringosta Islannissa, mukaan lukien kuinka kauan auringonlasku ja -nousu kestävät, minä kuukausina voit kokea keskiyön auringon Islannissa ja mitä ak...Lue lisääValaiden bongaaminen Islannissa: täydellinen opas

Lue, miksi valaiden bongaaminen Islannissa on niin suosittu aktiviteetti ja miten sen suosio on kasvanut viimeisten kahden vuosikymmenen aikana. Milloin on paras aika nähdä valaita Islannissa? Missä...Lue lisää

Lataa puhelimeesi Islannin suurin matkailumarkkinapaikka, jotta voit hallita koko matkaasi yhdessä paikassa

Skannaa tämä QR-koodi puhelimesi kameralla ja paina näkyviin tulevaa linkkiä lisätäksesi Islannin suurimman matkailumarkkinapaikan taskuusi. Lisää puhelinnumerosi tai sähköpostiosoitteesi, niin saat tekstiviestin tai sähköpostin, jossa on latauslinkki.