How long has Iceland been inhabited? Who were the first Icelanders? Where did they come from? Continue reading to learn all about the history of the Icelandic people.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Johan Peter Raadsig. No edits made.

Why You Can Trust Our Content

Guide to Iceland is the most trusted travel platform in Iceland, helping millions of visitors each year. All our content is written and reviewed by local experts who are deeply familiar with Iceland. You can count on us for accurate, up-to-date, and trustworthy travel advice.

- Master the fundamentals of the History of Reykjavík

- Discover everything you need to know about the fascinating History of Iceland

Icelanders, largely due to the success of the women in international beauty pageants and the men in strongman competitions, have a stereotype abroad of looking like something between a normal Scandinavian and a clichéd Viking.

The women are seen as fair, pale and beautiful, whereas the men are seen as rugged, muscular and bearded. All are usually seen as blonde-haired and blue-eyed, and thus classically Nordic.

While many Icelanders do look this way, it tells surprisingly little of their heritage and where they came from. From before the nation’s formation in 930 AD to the present day, the people who have called Iceland home have been an amalgamation of different cultures and backgrounds, not just descendants of the Old Norse.

Their heritage is thus a far deeper and more interesting story than international stereotypes may lead you to believe, and this article will plumb the depths of history to find out where the people of Iceland truly came from.

The People of the Pre-Settlement Era

In the early 9th Century, the Norse ‘discovered’ Iceland, in the same way that they later ‘discovered’ the Americas; they reached both lands, certainly, but they were not the first to, as both had people already living there.

While in the case of the Americas, there were millions of people in multiple civilisations, in Iceland, there were but a few individuals. The island was at least a temporary base for Gælic monks on the Hiberno-Scottish Mission, and although very little is known about what exactly they were doing, historians are certain that they were here.

A cabin, abandoned somewhere in the late 8th or early 9th Century, predates the first official ‘settlers’, and archaeological remains in Kverkarhellir cave and Seljaland Farm date to around the year 800. Within the cave, a cross was found etched on the wall in the Gælic style.

It is believed that all of these monks left with the arrival of the Norse, but the truth remains unknown; it is possible some stayed, or were enslaved, and thus would have had some influence on the beginnings of the Icelandic nation.

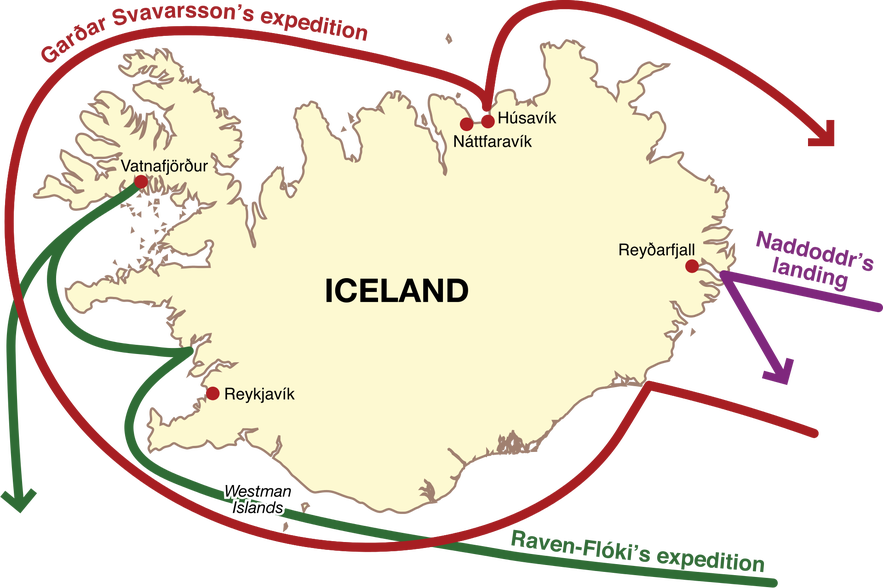

The first Norseman to set foot on this island, however, was a man called Naddodd, who was lost en route from Norway to the Faroe Islands in the early 800s. He noted that the land was vast, but after ascending a mountain and seeing no smoke rising from anywhere, determined that it was uninhabited and left.

He was followed by Garðar Svavarsson, a Swede who wintered in the North of the country before departing himself. What is little-known about him, however, is that his travelling companion, a man called Náttfari, and two of his slaves, a man and a woman, escaped as he was departing, and formed a farm on Skjálfandi bay.

Although not recognised officially as the first Icelanders in medieval literature, they were the first to create a permanent home here around 870 AD, four years before the Settlement Era truly began. Their home was just across the water from the town Húsavík, which means ‘Bay of Houses’, possibly because of the buildings raised by Náttfari and his companions.

Iceland was also visited by Hrafna-Flóki prior to the Settlement Era, who gave the land its current name and cursed its inhospitable climate. His warnings, however, did not deter Ingólfur Arnarsson from arriving in 874 AD and forming the first officially recognised, permanent home in Reykjavík.

- See also: Top 9 Most Famous Icelanders in History

Icelanders in the Settlement Era

After Ingólfur settled in Iceland, he was followed by more and more Norsemen. Those who came were largely clans who did not wish to bend the knee to the first Christian King of Norway, Harald Fairhair. Farms, fishing outposts and villages began to form all around Iceland’s coast.

One could be forgiven for thinking that Icelandic stock, therefore, descended from Norwegians alone in this time. Unfortunately, however, as with most things in history, the true story is a lot darker.

En route to Iceland, the Norse would, in classic Viking style, pillage and plunder Irish settlements, and take slaves from them; most of these slaves were women who would go on to mother the first generation of trueborn Icelanders.

Evidence of the Irish influence on the early years in Iceland can be found across the country, particularly in the naming of locations. Vestmannaeyjar, for example, translates to ‘the Westman Islands’; the Westmen was what the Norse called the Irish, as prior to the Settlement Era, Ireland was considered the westernmost landmass in Europe. Patreksfjörður, meanwhile, was named after Saint Patrick, the patron saint of Ireland.

From 874 to 930 AD, more and more people and clans were arriving in Iceland, with a demographic of almost entirely Norwegian men and Irish women. By 930 AD, there were thirty-nine clans across thirteen district assemblies.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by the Arni Magnusson Institute. No edits made.

To help ease competition and conflict between them, it was in this year that the Alþingi—or national assembly—was formed in Þingvellir, establishing an Icelandic Commonwealth and what would later become the world’s longest-running parliament. This would mark the end of the Settlement Era.

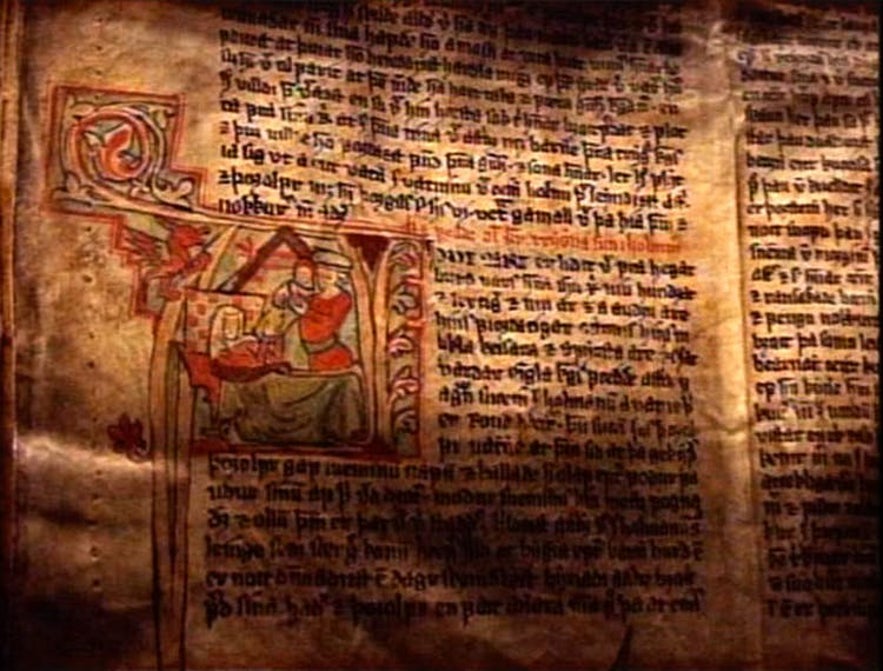

Everything we know about the Settlement Era in Iceland comes from Íslendingabók and Landnámabók. Both thought to be assembled by Ari Þorgilsson, these medieval texts catalogue the families and lineages in the country. While tedious tomes to leaf through, their importance is undeniable; without them, we would be blind to the history of Icelanders, and the early days of where they came from as a people.

Icelanders in the Commonwealth Era

The demographics of Iceland changed little in the Commonwealth Era, other than an influx of Christian missionaries, largely from Norway but to an extent from the rest of Europe, who got the country to abandon the Old Norse faith in the year 1000 AD.

There is one heavily debated potential influence on the Icelandic gene pool which perhaps occurred during this time, however. The small gene pool of Icelanders has an anomaly, where it appears some people have a DNA sequence that otherwise is only found in Native American populations.

*For more information about the Native American DNA debate, check the comments at the bottom of the page.

How this came about is unknown, but as this was the era in which Erik the Red settled in Greenland and his son Leif the Lucky settled in Newfoundland, it is very possible that a First American was brought back to Iceland as a wife or slave. There are no written accounts of this, however, so it is a contentious point.

Almost all foreign contact and trade outside of Greenland and America at this time was with Norway, with whom Icelanders did their best to foster a good relationship. Unfortunately, however, the rulers of Norway used this to their advantage, influencing certain chieftains to support the Commonwealth in joining their Kingdom, including Snorri Sturluson, the iconic medieval writer who wrote Snorri’s Edda, a work of literature detailing Norse cosmogony, pantheon and myths.

- See also: Icelandic Literature for Beginners

This caused a civil war within Iceland, and supporters of the Kingdom eventually won out. By 1234, the island nation fell under the rule of the Norwegian Crown and for the next seven-hundred years, Iceland would be under the control of foreign powers, and though this next era would mark their hardest times, it also was a time when new influences would begin to creep into the roots of the Icelandic people.

Icelanders in the Colonial Era

The Colonial Era began with a mini Ice Age, so with crops dying and fertile land becoming barren, it is no wonder that only a handful of people chose to move to Iceland in this time. Christian missionaries, largely from Germany, Norway and the Celtic world, continued to pass through, however, and had a small influence on the demographics.

The largest change occurred when, at the death of the last man in the Norwegian Royal Line, Norway joined the Kalmar Union with Sweden and Denmark, the latter nation being the one with the most power. While the Norwegians had been distant rulers that had brought some level of prosperity through their purchase of Icelandic fish and wool, the Danish wanted greater consolidation of influence, without the need for these products.

As such, Iceland became oppressed, impoverished and with an ever-decreasing influence over its own affairs. Danish merchants and traders who settled in the country’s coastal towns were largely the only ones with any quality of life, and the only people who had any reason to migrate to Iceland. Even then, however, they were few and far between.

Technological advancements as the years went by brought about different influences to Iceland, however. The whaling industry began to explode in the middle of the second millennium, and, though the country’s infertile soils deterred settlers, its fertile waters drew ships from across Europe to its coasts.

The relationship between Icelanders and these foreigners is little known, but records show that they would stop at Icelandic ports and trade with the locals. It was a largely peaceful, mutually beneficial arrangement, with the huge exception of the Basque Whalers who were notoriously massacred in the Westfjords in the 1600s.

Undoubtedly, there was some mixing between the sailors and whalers and the Icelandic women, but due to the shame associated with such an affair, such incidents are little recorded. When women fell pregnant out of wedlock or in such ‘scandalous’ manner, it was customary to claim the father was a ‘hidden person’ to avoid embarrassment for the family and punishment for the mother.

- See also: Folklore in Iceland

Regardless of the extent of this influx of genes contributing the Icelandic heritage, the biggest change to the demographics occurred with a mass exodus from Iceland with the eruption of Laki from 1783 to 1784. The lava, pollution and subsequent famine killed a quarter of the population and forced another quarter to flee, largely to North America.

Though this took a huge amount from the Icelandic people, some of those who left did return, some with new families, and thus new Icelanders.

One person from outside of Iceland who we know significantly changed the country’s demographic, however, was Hans Jonatan, the first black person known to have settled in Iceland and formed a family here.

Jonatan’s story is both tragic and heartwarming; born a slave on the Danish island of St. Croix in the Caribbean, he was moved to Denmark with his ‘owners’ around the year 1800. He escaped the masters and joined the Danish Navy to fight in the Napoleonic Wars, for which he was greatly esteemed.

However, following the war, he was brought to court where he had to argue his freedom, and though slaveholding was only legal in Danish colonies, not Denmark itself, the judge ruled that he had to return to chains in the Caribbean.

Jonatan, however, escaped once more, and disappeared from the Danish record. It was not until centuries later that it was discovered internationally what had happened to him. Hans had managed to get to the Icelandic village of Djúpivogur in 1802, where he was met with respect from the locals for his excellent Danish.

He went from being a peasant farmer to running a local trading post, and married an Icelandic woman, Katrín Antoníusdóttir. They had two children that survived to adulthood, the first Icelanders known to be biracial, and now have nearly a thousand living descendants, one of whom became prime minister.

Unfortunately, as the 1800s rolled in, ominous European theories of eugenics and ‘racial biology’ began to bleed into Icelandic society. The nation thus went from being oblivious to the outside world and circumstantially happy to take in outsiders, to somewhere that repelled foreign influence—until they were forced to change in World War Two, at least.

Icelanders in World War Two

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by United State Army. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by United State Army. No edits made.

In 1940, Denmark was invaded by the Nazis. This did not immediately cripple Iceland; it had had Home Rule since 1874, with the powers of the Alþing increased in 1904 and 1918 to the extent that it was considered a ‘sovereign state’ that shared the Danish king.

They were thus able to economically continue after the invasion, but were left with no protection; as has always been the case in Iceland, it had no standing military of its own. The Allies, therefore, intervened to remedy this.

British troops invaded Iceland in 1940; with its strategic position in the Mid-Atlantic between the then USSR, the UK and the USA, it could have changed the tide of the war if the island went into the hands of the Axis powers. There were no casualties in the invasion; the communications were simply taken over, the German residents were arrested, and a note was pinned on the post-office door that told locals, in broken Icelandic, of the new circumstances.

Icelanders, who had claimed neutrality, were not thrilled with the new presence, but accepted it, and were permitted to carry on their business as usual. For a while, it seemed that little had changed, although this did not last any longer than approximately nine months.

The Icelandic women can hardly be blamed for being excited by the new arrivals. Many Icelandic men were conservative, unhygienic, rowdy and aggressive, whereas the newcomers were civil, polite, well-dressed and clean.

This became even more the case when the British were replaced by the Americans in 1941. As a phrase amongst Icelandic women went:

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by the Royal Navy. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by the Royal Navy. No edits made.

A great stigma began to surround those who took American men as lovers during the war to the extent it was given its own name: Ástandið, or ‘the Situation’. A special brochure was released for young women to inform them that they were responsible for the purity of the Icelandic race, and those that became ‘victims’ of foreign charm were ostracised.

As harsh as the judgement was, however, ‘the Situation’ was becoming increasingly common. The centre of everything in Iceland had become Reykjavík, and there were a great many opportunities for work due to the American presence; as such, there was a huge movement to the capital, especially amongst young people, whose ideals were not as conservative or rigid as their elders’.

- See also: A History of Reykjavík

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by USMC Archives. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by USMC Archives. No edits made.

Because of the aforementioned racism that bled into Icelandic culture from the 1800s to the start of the war, the Icelandic government insisted that white troops alone could be stationed in Iceland. This was not adhered to, and the birth of a biracial girl called Magnea was an enormous controversy; not only had she been conceived to an American, but a black American. It showed in her features, skin and hair.

Though her childhood was tainted by discrimination, Magnea was and is—being very much alive—known for her joyful personality, and throughout her lifetime has watched an enormous shift in attitudes. She is a pioneer in the sense that she proved in the modern era that one could still be a true Icelander without having blonde hair and blue eyes.

In 1944, the Icelandic nation declared full independence from Denmark. Though this would be the beginning of their current era, it was by no means the end of the shaping of the Icelandic people, nor of the American presence in the country.

Icelanders since Independence

Following independence and the end of the war, Iceland signed a controversial agreement with the USA, whereby they would have a permanent base in Iceland and provide the country’s defence. The American men who had thus ‘taken advantage of’ the Icelandic women were there to stay.

The stigma on Icelandic women who took American lovers did not ease for many decades. There were even cases of women being institutionalised to recondition them back into ‘normal’ behaviour, and their children, called ‘Ástandsbörn’, faced similar discrimination.

Even so, they were a bigger and bigger part of society with every passing year, growing until they had a strong enough collective voice to challenge bigotry and demand respect.

- See also: Gender Equality in Iceland

Since 1944, Americans have not been the only ones to change where the Icelanders of today originated, helping to challenge the traditional views of who Icelanders were.

With massive advancement in technology worldwide and an intense period of development domestically, Iceland entered the modern world as an independent nation. Though its island status prevented the full effects of globalisation from taking hold, it was and is heavily affected by an increasingly connected planet.

With more universities and opportunities in industries outside of fishing and agriculture, Iceland found that it needed immigration to fill gaps in the work market. This became much easier for those seeking to move to Iceland when the nation joined the EEA in 1994, and even more so when the Schengen Agreement came into effect in 1995.

The majority of these newcomers arrived from Poland; many British, Lithuanian, Latvian, Danish and German also emigrated over. The newcomers, however, were not only arriving from Europe. Iceland gradually began to be blessed with large Filipino and Thai communities, as well as a number of people arriving from North America and other parts of Asia.

By the time the US base at Keflavík closed in 2006, therefore, Icelanders had become a diverse group of people, with roots from around the globe.

Immigration to Iceland has increased more and more since the tourist industry has bloomed, particularly since 2010 (when the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull drew international attention to the island). As such, companies have had to hire many people from abroad to meet the demands of the exploding market, and many of them have chosen to settle and remain here.

Currently in Iceland, six percent of the population is born abroad, and about ten percent are considered first or second generation immigrants. First generation immigrants are set to represent fifteen percent of the population by 2030. The country has thus come a long way from telling its young women to ‘protect the bloodline’, and is now accepting newcomers from across the globe.

When determining where Icelanders came from, therefore, the truth today is everywhere. Of course, the oldest roots of the nation are Norse and Gælic, but as with the rest of the world, national and ethnic lines are blurring.

Where your family came from before settling in Iceland, therefore, is having less impact on how Icelandic you are considered; simply defining yourself as Icelandic, embracing the culture and language, is enough to be an accepted part of this fascinating and welcoming community.