Discover the fascinating folklore in Iceland, from tales of elves and trolls to sea monsters and land spirits. Explore Icelandic myths and legends hidden in the magical landscapes and their significance in Icelandic culture. Continue reading to learn more!

Since the first Norse settlers reached the island, Icelanders have told fantastical tales of encounters with the many strange forces with which they share the land. The land is steeped in myth and mystery, where stories of the supernatural reflect the connection Icelanders have with their dramatic landscape.

Why You Can Trust Our Content

Guide to Iceland is the most trusted travel platform in Iceland, helping millions of visitors each year. All our content is written and reviewed by local experts who are deeply familiar with Iceland. You can count on us for accurate, up-to-date, and trustworthy travel advice.

Whether you're staying in Reykjavik accommodations or heading out for epic self-drive tours with a rental car, you'll find traces of folklore everywhere. Even the most unassuming rock can be surrounded by Icelandic myth, and you can get to know some of the most famous local stories on many guided tours, like this folklore walking tour in Reykjavik.

Get to know the magical world of Icelandic folklore, where every mountain and lava field might hold a story. From elves and trolls to sea monsters and ghostly tales, read on to uncover the Iceland myths that are truly unique!

Key Takeaways

-

Folklore in Iceland is deeply rooted in the country's history, blending pagan beliefs with nature and mythology.

-

Icelandic folklore creatures like elves, trolls, and ghosts are said to inhabit the landscape.

-

Iceland folklore reflects the harsh natural environment, with stories explaining natural phenomena and survival.

-

These legends continue to influence modern Icelandic culture, from storytelling to tourism and environmental decisions.

The Hidden People and Elves in Iceland

"Stóð ég úti í tungsljósi" artwork depicting the hidden people moving homes,1960-1970, by Finnur Jónsson (1892-1993). From the National Gallery of Iceland.

Elves are prominent figures in Northern European and Germanic mythology, often described as beautiful, elegant, and eternal beings with great powers. Icelandic elves follow this tradition but have distinct characteristics unique to local folklore.

In Iceland, elves are believed to live in rocks and cliffs, leading lives similar to humans. They keep livestock, cut hay, row fishing boats, pick berries, and even attend church on Sundays. Though they resemble humans, they are described as exceptionally beautiful and often possess great wealth.

There are many locations around Iceland that are said to be the homes of elves, like this "elf church" at the Dimmuborgir Lava Field by Lake Myvatn.

In Icelandic, these creatures are called both elves (álfar) and hidden people (huldufólk). The terms are used interchangeably, but "álfar" is the older term.

The term "huldumaður" (hidden man) first appeared in written sources around the 15th century, and "huldufólk" only in the 17th century, but over time, they have become just as common as "álfar."

The hidden people of Iceland are highly private, remaining invisible unless they choose to be seen, with the exception of certain occasions like New Year’s Eve or the summer solstice, when they're said to move homes.

If a human joins the world of the elves, which most often happens through marriage, the human usually disappears, rarely being seen by their friends and family again!

The historic Bustarfell turf farm in Vopnafjordur Fjord, East Iceland

There are many Icelandic tales that describe elves and humans helping each other in times of need, and humans often receive generous gifts for their help.

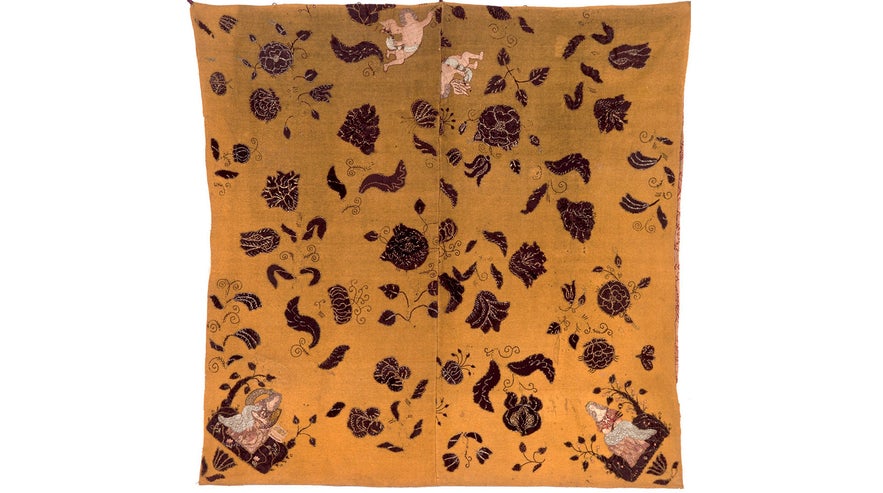

An example of this is the gold-woven altar cloth pictured below. According to an East Iceland folktale, this cloth was gifted to the lady of Burstafell in the Vopnafjordur Fjord by an elf woman as thanks for assistance in childbirth.

It's one of the only known artifacts directly related to elf folklore, and it's preserved at the National Museum of Iceland.

This altar cloth was supposedly made by elves. Photo taken from Safnahusið - House of Collections.

While there are plenty of stories of friendly interactions between elves and humans, the most common ones are about elves seeking revenge.

They're known to be highly protective of their homes and are said to cause harm to anyone who disrupts them. This can range from theft and kidnapping to bodily harm and even death!

Even today, there are examples of the fiercely territorial nature of elves, most famously when it comes to building projects and road construction. It's not unheard of that plans are altered to avoid causing damage to rocks and cliffs that are said to be homes of hidden people.

Photo from Felir, the road curving around the Álfhóll elf hill in Kopavogur.

One of the more well-known examples of this is Álfhóll, or "elf hill," in the town of Kopavogur. Since the 1940s, attempts to build a road through this hill have mysteriously failed.

The first effort was abandoned when funding ran out just before blasting could begin. A decade later, a second attempt was thwarted when heavy equipment and machinery repeatedly broke down without explanation. In the 1990s, a third attempt was made to remove part of the hill for road repairs, but powerful drills broke apart without even leaving a mark on the rock!

In the end, the elves won, and the pesky humans stopped trying to ruin their home. Today, the road simply narrows and curves around Álfhóll hill, which is now a protected site.

- See more about the Beautiful Bustarfell Turf House in East-Iceland

- See also: Úlfhildur the Elf-lady at Lake Mývatn in North-Iceland - Icelandic Folklore

Do Icelandic People Believe in Elves?

There have been supposed modern elf sightings in Hellisgerdi park in Hafnarfjordur.

If there's one thing you may have heard about Iceland, it's that most Icelanders believe in invisible elves. This has been covered by major news outlets around the world and greatly exaggerated, but is this actually true?

For most Icelanders, the answer is a full no. Yet, in a way, it’s also a little bit true.

Icelandic children grow up hearing tales of hidden elves who live in nature, and disturbing them may lead to bad consequences. These stories encourage respect for Iceland’s landscape, which hides many natural dangers, and while most people today don’t literally believe in a hidden society in the rocks in their back garden, the cultural idea still remains.

In Hafnarfjordur, children are told stories about elves living in the Grahelluhraun lava field, who will become angry if disturbed. In reality, the stories are meant to prevent them from playing in the field, keeping them safe from the dangerous cracks in the lava formations.

The belief in hidden people is similar to superstition in many ways. You may not truly believe that breaking a mirror causes bad luck or telling a friend that you've "never had a parking ticket" will now surely result in it happening, but the thought may still cross your mind in the moment.

As folklorist and professor Terry Gunnell has described it, if you want to build a porch in your backyard in Reykjavik and have to remove a rock to do so, but your neighbor tells you a story about an elf living there who may seek revenge...well, will you risk it?

Some Icelanders will hesitate and even build their porch around the rock instead, which speaks volumes. And why not let the story live on? Isn't it more fun to let the rock be in peace anyway, whether you believe the story or not?

You can see an elf-rock in the oldest part of Reykjavik, the Grjotathorp Neighborhood!

In short, the great majority of Icelanders do not believe in elves, but a sizable percentage are hesitant to completely deny the existence of supernatural beings like the hidden people. Surveys noted in this article on Icelandic folk belief show this group is getting smaller with each decade, possibly in part because of the amount of attention this "strange" cultural heritage has attracted internationally.

It’s worth noting that a small number of Icelanders claim to fully believe in elves and even say they can see and speak with them, contributing to the misconception that all Icelanders hold these beliefs. There's even an Icelandic Elf School in Reykjavik, where you can take a short class about the hidden people from a supposed elf expert.

Regardless, the hidden people are still a fun piece of folklore to remember when exploring Iceland. Seeing the diverse scenery, lava formations, towering mountains, craters, and glaciers is already incredible, but made even more so with the stories of magical and majestic beings hidden among the vast nature.

Other Types of Icelandic Fairytales

Photo from Flickr, by Erico Silva. The Dverghamrar cliffs are said to be home to Icelandic dwarfs and elves.

While elves and the hidden people are the most famous part of Icelandic lore internationally, the country has a very diverse storytelling tradition. There are many other kinds of fairytales you'll find in Icelandic folklore collections, and here are some of the most common ones!

Icelandic Sea Monsters

Iceland folklore is rich with tales of sea monsters, creatures believed to inhabit the country’s rugged coastlines and deep waters. These monsters are as much a part of Icelandic mythology as its elves and hidden people, with stories passed down through generations.

Iceland folklore is rich with tales of sea monsters, creatures believed to inhabit the country’s rugged coastlines and deep waters. These monsters are as much a part of Icelandic mythology as its elves and hidden people, with stories passed down through generations.

Some of the most famous Icelandic sea monsters include the "hafgúfa," a gigantic sea creature said to resemble a whale or sea serpent, and the "nykur," a deceptive, horse-like being that appears by the water’s edge. It lures unsuspecting riders onto its back, then dives into the water, drowning them.

There are many more beings said to roam the Icelandic coastline, some dangerous and others simply unsettling and strange. Even today, some people claim to have seen these creatures, placing them within the realm of cryptozoology, which studies and searches for animals known only through stories and folklore rather than scientific evidence.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Rob Oo. No edits made.

Some lakes near Reykjavik are said to be home to such creatures. Lake Kleifarvatn on the Reykjanes Peninsula and Lake Hvaleyrarvatn in the town of Hafnarfjordur are rumored to be homes of monsters like the "nykur," so keep an eye out if you plan to visit!

These Icelandic creatures have their own dedicated museum in the mystical Westfjords, which is a great addition to summer self-drive tours of the region.

The Icelandic Sea Monster Museum is located in the town of Bildudalur, just an hour's drive from the majestic Dynjandi Waterfall and two hours from Isafjordur, the largest town in the region.

- The Sea Monster Museum is one of the Top 10 Weirdest Museums in Iceland

- See also: Arnarfjörður Fjord in the Westfjords of Iceland - the Sea Monster Fjord of Iceland!

Icelandic Trolls

"Nátttröllið á glugganum" or the Night Troll by the Window, 1905 by Ásgrímur Jónsson (1876-1958). From Listavefurinn/The National Gallery of Iceland.

Trolls are central figures in Icelandic folklore and are usually described as giant, stupid, and greedy, but sometimes kind and wise. Like elves, trolls become angry when they're disturbed, but one can expect to be richly rewarded when helping a troll in need!

Icelandic trolls are capable of extraordinary magical feats and are known to cast terrible spells and enchantments. However, due to their low intelligence, humans can often free themselves of their traps quite easily.

Artwork depicting the story of Búkolla, 1949, by Ásgrímur Jónsson (1876-1958). Photo taken from Art Museum of Árnessýsla/National Gallery of Iceland.

Icelandic trolls usually live in mountains, caves, or remote areas, away from human settlements, where they only come out when it's dark. A key feature in Icelandic troll folklore is that trolls turn to stone if exposed to sunlight, which is why many natural rock formations across Iceland are said to be petrified trolls!

One of the most well-known examples of this is the Reynisdrangar Sea Stacks on the Reynisfjara Black Sand Beach near the town of Vik. One story states that the rocks were trolls pulling a ship to shore, but they stayed out too late and got caught by the sunlight, transforming into rocks.

- Plan your trip with the Ultimate Guide to Iceland's South Coast

- See also: Top 9 Things To Do in Vik

Another story tells of a woman who was kidnapped and killed by two trolls. Her husband followed the trolls to the Reynisfjara Beach and tricked them into coming out during daylight, turning them into the Reynisdrangar sea stacks.

Another story tells of a woman who was kidnapped and killed by two trolls. Her husband followed the trolls to the Reynisfjara Beach and tricked them into coming out during daylight, turning them into the Reynisdrangar sea stacks.

If you're planning to pick up a budget rental car in Reykjavik and head out for an adventure around Iceland, keep an eye out for more locations like these.

Many places are named after trolls, such as the Trollaskagi Peninsula or "troll peninsula" in North Iceland, the Naustahvilft Troll Seat in the Westfjords, and the dramatic Skessuhorn Mountain in the Borgarfjordur Fjord (Skessa is the term for a female troll)!

- The Troll Peninsula is one of the 15 Hidden Destinations in North Iceland

Icelandic Ghosts

A watercolor painting depicting the story of the Deacon of Myrka river, or "Djákninn á Myrká," 1916-1918, watercolor by Ásgrímur Jónsson (1876-1958). Photo from National Gallery of Iceland.

Icelandic folklore is filled with spooky tales of ghosts or "draugar." There are distinct types that each bring their own kind of terror and have their own rich storytelling traditions.

A common type of Icelandic ghost is the "uppvakningur," a type of zombie. These spirits are reanimated by someone using magic, usually for a dark purpose. They are typically controlled by the person who raised them and are associated with sinister acts and malevolent intent.

These creatures don't always look human either, as seen in the case of the "Þorgeirsboli," a monstrous bull from North Iceland. It was created as revenge for a rejected marriage proposal and was done by flaying a calf so its hide dragged behind it.

It was then combined with elements of a dog, man, infant, cat, mouse, bird, air, and two sea monsters to give it the ability to transform and spread its terror around Iceland.

Artwork depicting the Þorgeirsboli bull from 1929 by Jón Stefánsson (1881-1962). From the National Gallery of Iceland.

Icelandic folklore also describes a kind of follower known as "fylgja." These ghostly figures are said to attach themselves to individuals or, in some cases, entire families, following them through generations.

A "fylgja" can take on many forms, often appearing as a human-like shadow or even an animal. While they are sometimes considered protectors, they are more commonly viewed as bringers of misfortune or tragedy, their presence signaling impending danger or hardship.

Common versions of these ghosts are "móri" and "skotta". The móri is a male ghost, often depicted wearing a reddish-brown sweater or jacket and a large hat or balaclava hanging from its neck. The photograph below is said to show a móri to the right, approaching the sailors at work.

The blurry figure to the right in this photo is said to be a "móri," a male ghost, approaching the sailors. From Vísindavefurinn/Draugastertið á Stokkseyri.

The skotta, in contrast, is female and wears traditional Icelandic head coverings that are supposed to curve forward, but on them, the headpiece points backward or hangs down like a tail. They are also said to wear red socks and habitually suck on their thumb.

Both the móri and skotta are described as childlike yet mischievous. Their behavior ranges from ruining food to harming or killing farm animals. In extreme cases, they may even kill people.

However, they are said to be somewhat appeased when provided with food.

"Djákninn á Myrká", 1931, by Ásgrímur Jónsson (1876-1958). Photo taken from National Gallery of Iceland.

An Icelandic ghost type that you may be most familiar with is the "afturganga," which translates to “one who walks again.” These are individuals who return from the dead and often have unfinished business or seek revenge, like ghosts of many other cultures.

A ghost's appearance is often linked to the cause of death and the reason why it still roams the earth. Ghosts of drowned men are usually seen wearing damp sea wear, and those who have risen from the grave generally wear a white shroud.

A unique type of "afturganga" is the "útburður," the spirit of a child abandoned in nature, typically wrapped in the clothing they died in and characterized by a whistling whine that can be heard from long distances.

In one of Iceland's most famous ghost stories, the Deacon of Myrka River, a young woman named Guðrún unknowingly accepts a ride to church from her dead fiancé, who has returned as a ghost.

She begins to suspect something is wrong when she notices a white patch at the back of his head and hears him call her "Garún" instead of "Guðrún," as he cannot speak the name of God (Guð in Icelandic). The white patch was his skull, showing the injury that caused his death.

The modern graveyard by the Myrka River in North Iceland.

As they near the graveyard, the Deacon tries to pull Guðrún into an open grave, but she manages to escape just as he falls in, trapping him. His spirit, however, continues to haunt her, and a sorcerer is eventually summoned to exorcise the Deacon's restless ghost.

In Icelandic folklore, exorcisms are the most common way to banish a ghost, but not the only method. In one story, the vengeful spirit of a woman named Gunna haunted the Reykjanes Peninsula, driving people to madness.

She was tricked into following a ball of yarn into a boiling hot spring, where she became trapped. The Gunnuhver Hot Spring is said to hold her spirit to this day and has become a popular stop on Reykjanes tours.

There are so many interesting ghost stories in Iceland, and we highly recommend that you visit the Ghost Center in the town of Stokkseyri to learn more. You'll explore a large ghost maze with recreations of many iconic Icelandic ghost stories.

It's just a 15-minute drive, 9 miles (14 kilometers) from the town of Selfoss, and can be a fun cultural addition to South Coast tours or longer Golden Circle tours if you have a rental car!

- See also: Top 8 Things to Do in Selfoss

Icelandic Magic and Mythical Abilities

Stories of magic and mythical abilities are deeply ingrained in Icelandic folklore, reflecting a long-standing belief in the supernatural. Historically, witchcraft and sorcery in Iceland have a unique cultural narrative.

Stories of magic and mythical abilities are deeply ingrained in Icelandic folklore, reflecting a long-standing belief in the supernatural. Historically, witchcraft and sorcery in Iceland have a unique cultural narrative.

Unlike the witch hunts of Europe and North America, where women were primarily accused of magic, Iceland’s witch trials in the 17th century mostly targeted men. In fact, only one woman is confirmed to have been burned at the stake for accusations of magic in Iceland, while 20 men were.

These men were often accused of practicing magic, or "galdrar," characterized by runic symbols called "galdrastafir" that could be used for protection, curses, controlling the elements, and more. A total of 170 Icelanders were prosecuted for magic in the 17th century, with most of them being let off...unburned.

The Westfjords of Iceland were especially known for their many stories of witchcraft, and today, you can learn all about it at the Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft in the town of Holmavik.

Beyond witchcraft, Icelandic folklore also tells of mythical abilities like "skyggni," a type of second sight. Those with this ability are believed to be able to see the dead and other spiritual forces invisible to others. This ability can supposedly be inherited, though it is very rare.

Precognitive abilities, or the skill of gaining knowledge of the future, are another common theme, especially through dreaming. Many stories describe individuals being "berdreyminn," meaning that they receive warnings or guidance in their sleep. These dreams are far more vivid and detailed than typical "dream signs" and were historically taken very seriously.

Many storylines in the sagas of Icelanders involve a character dreaming of events in the future, which then eventually take place later in the saga.

These are widespread themes in Icelandic folktales and still resonate with many people today. It’s not uncommon for Icelanders to believe in ghosts or claim to see them. Modern stories of receiving messages through dreams are also fairly common, with many accounts of people learning the gender of an unborn child or being informed of a loved one’s death beforehand!

- Check out Icelandic Proverbs & Sayings

The Land Wights of Iceland

The Land Wights of Iceland are a unique part of Iceland mythology, revered as powerful guardians of the island, each presiding over one of its four quarters. According to the Heimskringla saga of King Olaf Tryggvason, these mythical protectors were summoned to defend Iceland from an invasion plotted by the ambitious King Harald Bluetooth.

To scout for vulnerabilities, Harald sent a wizard in the form of a fearsome whale, but every attempt to come ashore was thwarted by the mighty Land Wights.

In East Iceland, a dragon awaited in the Vopnafjordur Fjord, its fiery breath scorching the sea, surrounded by terrifying snakes and spirits that sent the whale-wizard fleeing. The north was protected by an eagle with wings wide enough to stretch across the Eyjafjordur Fjord, touching the mountains, accompanied by sharp-beaked birds ready to strike.

The Eyjafjordur Fjord in North Iceland is very wide. It's home to many islands and towns like Akureyri.

In the west, a huge bull stood guard by Breidafjordur Bay, its horns lowered, followed by more spirits. Finally, along the South Coast, a towering giant with an iron staff emerged, taller than all the mountains in Iceland and followed by an army of jotuns. He intimidated the wizard back to sea and back where he came from.

While the dragon, eagle, bull, and giant originate from a specific written source, there are multiple mentions of early settlers showing respect to the protective spirits of the land, indicating that these beings have roots in genuine folk belief. Today, these Land Wights are featured on Iceland’s coat of arms and on Icelandic krona coins, symbolizing strength and resilience.

- Learn about the Best Attractions by the Ring Road of Iceland

- See also: Guide to the Icelandic Krona

Christmas Folklore in Iceland

The arrival of the Yule Lads marks the start of Christmas in Iceland. These thirteen brothers, who are direct descendants of trolls, live in the mountains along with their troll mother, Grýla, and their stepfather, Leppalúði.

Originally, the Yule Lads were criminal pranksters who took turns sneaking into farms where they stole, pestered, and plundered. Each has a descriptive name that reflects his favorite form of mischief.

"Door Slammer" liked to slam doors during the dark of night, "Sausage-Swiper" would hide in the rafters where he snatched smoked sausages, and "Candle-Stealer" stole candles, which in those days were made of edible tallow.

Photo from Visit Mývatn. The Yule Lads at the Dimmuborgir Lava Field by Lake Myvatn.

Today, the Yule Lads have turned over a new leaf and serve a similar purpose to Santa Claus.

Icelandic children place one of their shoes on their windowsill, and each of the thirteen nights before Christmas Eve, one of the thirteen Yule Lads leaves either small gifts and treats or potatoes, depending on the child's behavior throughout the year.

A sculpture of Grýla with her cooking pot, ready for misbehaving children.

Potatoes in your shoe are not the only danger of behaving badly, however, as their mother, Grýla, likes to kidnap and eat disobedient children. To complete the lovely family is the terrifying Jólaköttur or Yule Cat, a huge beast that's known to eat those who have not received new clothes for Christmas.

During the festive season, towns across Iceland light up with festive decorations, Christmas markets, and events, and it's common to spot the Yule Lads and their family wandering around Reykjavik. You can even find a sculpture of the cat in Laekjatorg Square. It's a very charming time for winter vacations and to enjoy the unique culture of Iceland!

- Learn about Iceland in Winter - The Ultimate Travel Guide

- See more: New Years in Iceland

Notable Icelandic Folklore Characters

There are many characters that have a special place in Icelandic folklore, either as common names and themes or having many stories of their own. Here are some that you should know from Icelandic folk stories!

There are many characters that have a special place in Icelandic folklore, either as common names and themes or having many stories of their own. Here are some that you should know from Icelandic folk stories!

Ása, Signý, and Helga

Ása, Signý, and Helga are an iconic trio in Icelandic fairy tales, appearing in many stories involving trolls, elves, curses, and spells. These sisters often serve as stand-in characters for a variety of tales, much like using "John Doe" to refer to an everyman figure.

Ása is sometimes called Ásný or Sigríður, but she's usually the oldest. Helga is the youngest and is commonly depicted as the outlier. She is often mistreated by her family, but eventually rewarded for her perseverance through hardship.

In many stories, her trials lead to her two older sisters facing consequences for their selfishness or cruelty toward her. This dynamic makes their stories rich with moral lessons, adding to their popularity in Icelandic folk tales.

The Icelandic Cinderella - Mjaðveig Mánadóttir

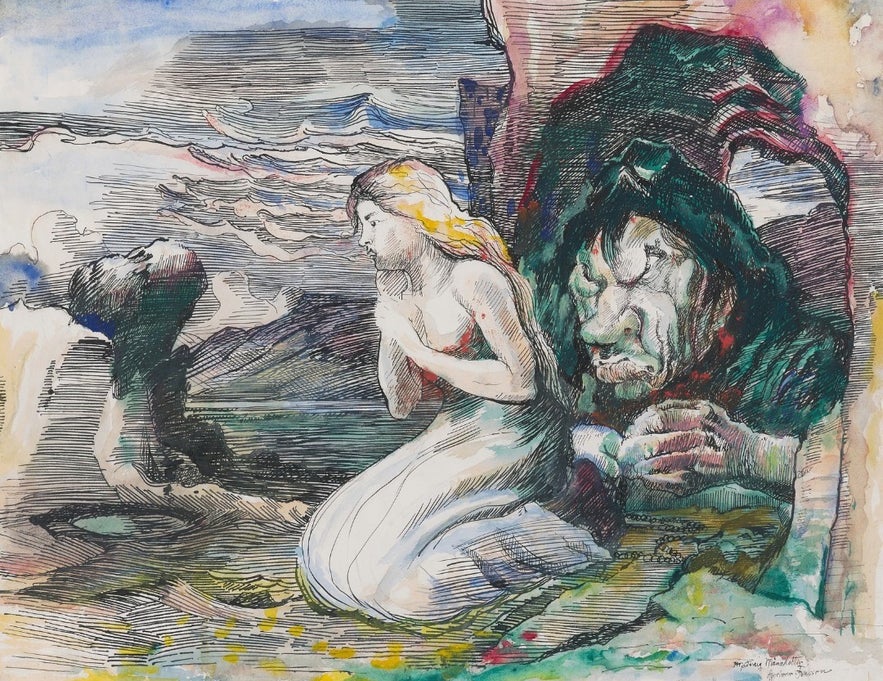

Artwork depicting Mjaðveig Mánadóttir and her troll stepmother, 1957-1958 by Ásgrímur Jónsson (1876-1958). From the National Gallery of Iceland.

When people talk about "the original Cinderella story," they often mean the story written by Charles Perrault in 1697. However, Perrault didn’t invent the tale. It’s much older, shaped by centuries of oral tradition, and adapted across cultures.

Versions of the Cinderella story exist in China, Vietnam, Sweden, and Iceland, where she is known as Mjaðveig Mánadóttir.

There are multiple stories about Mjaðveig Mánadóttir, but these Icelandic versions include familiar elements: an evil stepmother and stepsister, the guidance of a mystical mother figure, the loss of a shoe, a princely figure who finds it, followed by marriage and a happy ever after.

What may be less familiar, however, is that the stepmother and sister are usually trolls in disguise, and in some versions of the tale, they face a dark punishment. The stepmother is forced to eat her own daughter before meeting her own grim fate!

The Wyrm of Lagafljot Lake

The Wyrm of Lagarfljot, or Lagarfljótsormurinn, is a legendary creature said to dwell in the Lagarfljot Lake in East Iceland. Described as a large, snake-like creature, the wyrm has been a subject of fascination and fear for centuries.

One story states that it originated when a girl placed a gold ring on a small worm, hoping it would grow in size and bring her wealth. Instead, the worm grew monstrously large, so much so that it was thrown into Lagarfljot Lake, where it continued to grow, turning into the creature of legend.

Reports of the wyrm date back to the 14th century, when it's said to have risen so high that a ship with full sails could easily sail underneath it. It's commonly described as terrorizing locals and animals by spewing poison, and today, you can supposedly still see it rise from the lake on occasion.

The most recent documented sighting is from 2012, when a video captured a mysterious shape moving in the Lagarfljot Lake. It sparked renewed interest in the Icelandic legend of the Lagarfljot wyrm and drew comparisons to Scotland’s Loch Ness Monster.

The most recent documented sighting is from 2012, when a video captured a mysterious shape moving in the Lagarfljot Lake. It sparked renewed interest in the Icelandic legend of the Lagarfljot wyrm and drew comparisons to Scotland’s Loch Ness Monster.

If you’re visiting the Eastfjords or the nearby town of Egilsstadir, make sure to keep an eye on the lake.

If you happen to be planning to camp in Iceland or rent a campervan, there is a beautiful campsite in Atlavik Cove on the edge of the Lagarfljot Lake, which is a great option if you hope to spot this legendary creature!

- Check out the Top 9 Things to Do in Egilsstadir

- See more: The Best Places to Visit in East Iceland

FAQ's About Folklore in Iceland

Here are some of the most common questions about folklore in Iceland.

What Mythical Creatures Are in Iceland?

Icelandic folklore features elves, trolls, hidden people (huldufólk), sea monsters, and ghosts — beings often tied to the natural landscape.

What Is the Legend of Iceland?

The legend of Iceland is rooted in its folklore, where stories of magical creatures and powerful nature spirits explain the land’s mysteries and beauty.

What Are Iceland Folktales?

Icelandic folktales are traditional stories passed down through generations, often involving supernatural beings and moral lessons inspired by nature.

What Is the Elf Folklore in Iceland?

In Iceland lore, elf stories center around the belief in hidden people who live in rocks and hills. Many Icelanders respect these beings and their invisible world.

Discovering Iceland Through Folklore

Icelandic folklore is an important part of the country’s culture and history, shaped by its unique landscapes and traditions. Stories of hidden people, trolls, sea monsters, and other mythical beings reflect Icelanders' connection to nature and their efforts to explain the unknown.

For visitors, Icelandic folklore offers a deeper way to experience the country. Whether exploring museums, joining guided tours, or learning about local stories, it adds another layer to understanding Iceland’s heritage.

To dive deeper, try the folklore horseback riding tour through lava fields said to be home to elves, or explore Reykjavik’s hidden tales on the private Reykjavik folklore walking tour. From elves to sea monsters, Iceland’s folklore continues to inspire curiosity and wonder, making it an unforgettable part of any trip!

Which stories would you like to hear more about? Are there any folklore locations you'd like to visit? Do you already have a favorite Icelandic story or figure? Have you visited Iceland before? Share your thoughts and experiences in the comments below!