Gender Equality in Iceland

Gender equality—the right to equal opportunities and resources regardless of gender—is both a fundamental human right and one of the foundations for a prosperous and harmonious planet.

- Get to know gay rights in Iceland by reading Gay Iceland | All You Need to Know

- Find out more about Icelandic culture by reading A Snapshot of Iceland | Facts, Figures & Information

Though gender is often wrongly defined as an exclusive label to describe the sex of living creatures, the word has more recently applied solely to the human sphere, encompassing an individual's’ sense of self-identity, their social interactions and their daily behaviour. Of equal importance is the empowerment of women; the steady build of a culture that allows women to make choices for both their own benefit and the benefit of society as a whole.

Wycieczki kulturoznawcze

24-godzinna karta miejska Reykjavik z bezpłatnym wstępem do muzeów, galerii i basenów geotermalnych

10-dniowa samodzielna wycieczka po całej obwodnicy Islandii z najważniejszymi atrakcjami i Snaefellsnes

Elastyczna 48-godzinna karta miejska Reykjavik z bezpłatnym wstępem do muzeów, galerii i basenów geotermalnych

As of 2017, for the seventh year running, Iceland has topped the World Economic Forum’s survey for gender equality. Out of 144 countries, this small island has ranked number one in political empowerment amongst women, number one for closing the gender income gap (government ambitions look to finalise this in 2022) and boasts corporate quotas which ensure women currently hold 44% of representation on company boards.

“I’m not a man and I never have been and my principle has always been not to try to act like a man.”

Vigdís Finnbogadóttir, President of Iceland (1980-1996)

Women make up 66% of graduates from University, hold 30 of the country’s 62 parliamentary seats (48%), and elected their first female prime minister Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir from 2009 to 2013. On top of all of this, over 80% of women in Iceland make up part of the work force.

Icelanders are rightfully proud of these progressive statistics, but prouder still of the continuing fight for progress and the refusal to accept government compromises. This fight for progress is nothing new. Iceland and its Nordic cousins have always been considered more advanced in gender equality, with Finland, Norway and Sweden coming second, third and fourth respectively in the 2016 World Economic Forum survey.

This has almost been the case for two decades, with analysts pointing to the large scale female participation in the labour force, the closing pay gap and the opportunity for women to rise to positions of corporate and political esteem. Scandinavia’s development in this area has been put down to a number of factors, namely that all four countries above achieved 99% literacy rate for both sexes a number of decades ago.

In tertiary education, the gender gap has in fact been reversed, with more women attending university than men. Modern legislation is also perceived to be more advanced, with mandatory paternal and maternal leave for parents, making the balance between family and working life shared more easily between partners.

See also: What are Icelandic Women Like?

Gender in the Icelandic Sagas

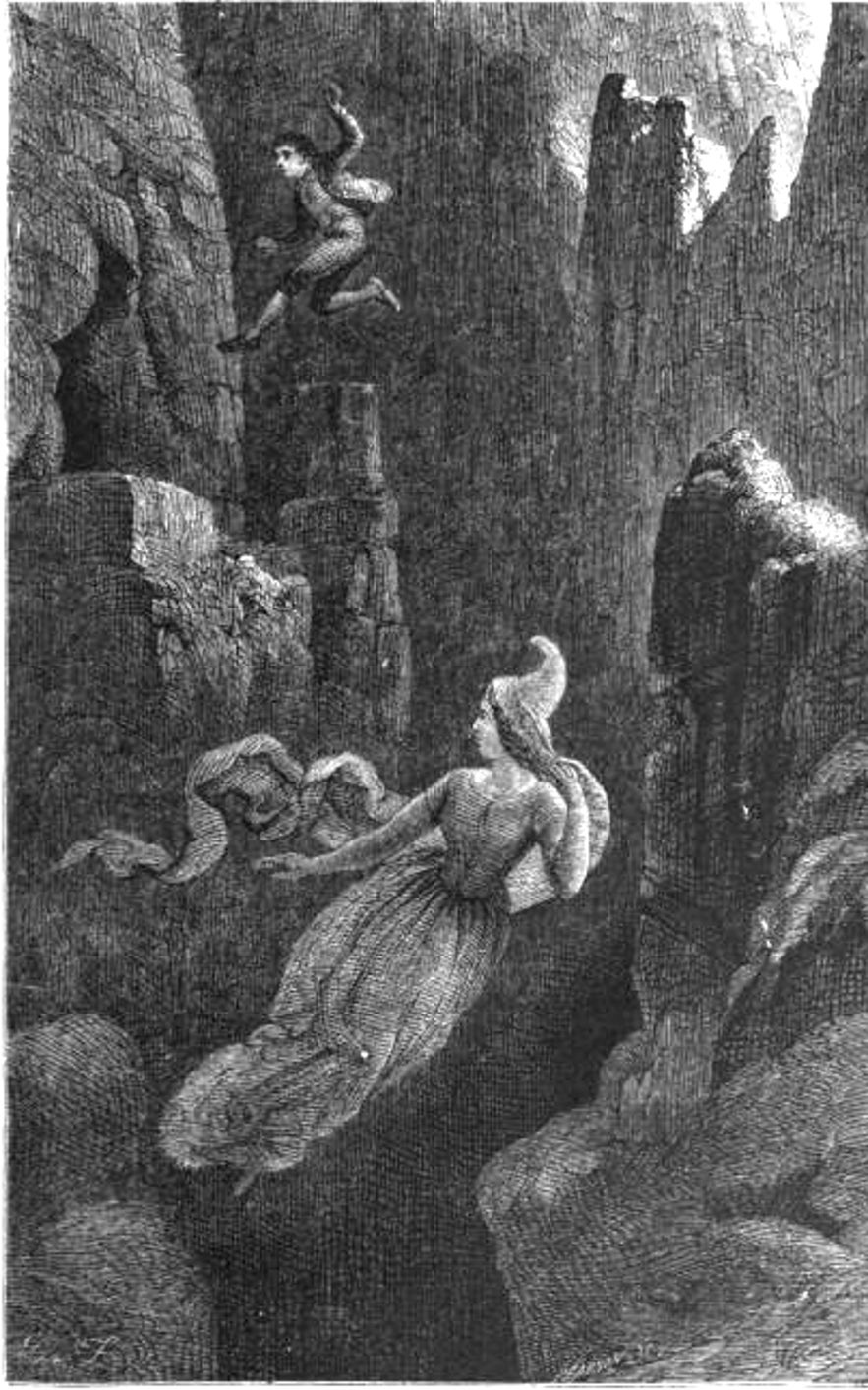

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Johann Baptist Zwecker. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Johann Baptist Zwecker. No edits made.

Women in the Icelandic sagas are mentioned fairly rarely but take a variety of roles, ranging from sorceresses to servant girls to Goddesses. There are a number of examples, however, that provide some insight into the independent-mindedness and strength of women in medieval Iceland, particularly the Laxdæla saga and Brennu-Njáls saga.

These traits can be traced back to Iceland’s history as a seafaring nation. Traditionally, the men were away from the family at sea, either fishing or participating in Viking raids, leaving their wives and families at home. By default, this left women in a position of power where they undertook traditionally male roles for the family: hunter, builder, farmer, etc.

Aside from this situation, women were constrained to a domestic life, their duties confined to child care, clothes making, food preparation and housekeeping. The medieval law book Grágás lays down these societal differences in writing, citing that women may not wear men’s clothes, cut their hair short or carry weapons, amongst others.

There were exceptions to this, however, an excellent example of which can be found in the Laxdæla saga.

The 9th-century settler Unnur Ketilsdottir (aka; “Aud the Deep-Minded”) was left widowed in Scotland after her husband was betrayed. Having made the decision to return to the remainder of her family in Iceland, Unnur secretly commissioned the building of a ship which she later captained to the shores of her homeland.

Under her command were twenty crewmen, made up of slaves and prisoners all looking to flee home. Upon their arrival in Iceland, Unnur granted her crew their freedom and secured her position as a respected, merciful leader. More than that, it cemented her reputation as a woman of action.

She would later settle land, run a farmstead and give charitably to her supporters. When she finally passed, the community buried her inside of a ship, an honour usually reserved for the land’s wealthiest men.

This is just one example of how women in Norse society could be granted a greater level of respect and freedom than their European counterparts. Women managed the finances of the household, ran the farmstead in their husband’s absence and could become wealthy landowners in widowhood. They were also protected by law from unwanted attention or violence. To strike a woman would largely mean death for the aggressor.

In Brennu-Njáls saga, the imposing warrior Gunnar struck his wife, Hallgerður Höskuldsdóttir, after she sent a slave to steal bread from a nearby farm. Given the famine at the time, this was considered a grave crime.

Hallgerður was quick to condemn Gunnar’s action, however, telling him that he would pay for hitting her in time. Later in the saga, Gunnar’s house is surrounded by enemies, an assault he can at first withstand thanks to his superior archery. It wasn't long though until Gunnar’s bowstring snapped in the midst of battle, and he called to his wife for aid;

"Does anything depend on it?" she said.

"My life depends on it," he said, "for they'll never be able to get me as long as I can use my bow."

"Then I'll recall," she said, "the slap you gave me, and I don't care whether you hold out for a long or a short time."

"Everyone has some mark of distinction," said Gunnar, "and I won't ask you again."

With that, Gunnar was overwhelmed by his enemies and killed in his home. Hallgerður was allowed to go free, though she was roundly condemned for her actions.

Helga the Fair is another example of how women were perceived through the eyes of medieval Icelanders, found in Gunnlaug's saga.

Helga was a woman of exceptional beauty, caught in a love triangle between the noble warriors Gunnlaugr Ormstunga and Hrafn Önundarson. Both men eventually perished fighting over her hand in marriage, and though she still deeply loved Gunnlaugr, she was quickly married off to another man. Helga lives the remainder of her life grieving for her fallen lover.

More often than not, women were known for their role as an ‘inciter’. The sagas are filled with stories about women goading their husbands to take action, vengeance if need be, to protect the familial honour. Academics have argued this position as the instigator arose from the woman’s inability to break through these gender roles themselves.

Women’s Suffrage in Iceland

The 19th and 20th century was a time of great change in Iceland, culturally, politically and socially. In 1845, the Danish Crown allowed the re-establishment of the Alþingi, later expanding its influence as a legislative and financial body. By 1904, Iceland had achieved home rule, lessening the crown’s influence over the country. In 1918, Iceland became a sovereign state, finally cutting all ties with Denmark and declaring independence in 1944.

Throughout this time, women’s suffrage was beginning to take hold.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Fr. Howell. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Fr. Howell. No edits made.

Parliamentarians discussed women’s suffrage on numerous occasions and were found to be in favour of it, proposing legislation quickly turned down by the more conservative Danish Crown. However, in 1850, Iceland was the first country in the world to grant equal inheritance rights to both men and women. In 1881, women were suddenly allowed to vote in local and parish elections. Twenty-one years later, women were eligible to represent these bodies.

The first steps toward change had been taken.

The first organisations centred on women in Iceland were formed in the latter half of the 19th century. In 1869, a woman’s association group was formed in the countryside and focused on women’s unity. There was no specific political goals mentioned by the group, though the group’s formation itself sparked an awakening in Icelandic culture and birthed a litany of other movements.

In 1874, a woman’s college was formed in Reykjavik, funded in part by women’s movements from abroad. It is still running. For the first century it was only for women, but in 1977 the first man attended it and it now educates both men and women.

The first outright political woman’s right organisation was founded in Reykjavik in 1894, the Icelandic Women’s Association. The group organised support meetings, lobbied parliament, distributed petitions and vehemently pushed obtaining the vote for women. A year after their formation, the group could boast a parliamentary petition of over 2000 signatories. In 1907, the group held a petition of over 11,000 signatories, signed by men and women from across the island. In 1911, women gained equal access to public grants, public office and education.

Finally, on June 15 1915, women over the age of 40 could vote in national elections, a victory blemished by the difference in voting age from that of men, 25. In 1917, women were granted the same rights over their children as men. In 1920, the age barrier to voting eligibility for women was removed entirely.

During these two enormous historical landmarks, Icelanders had begun to move from their farmsteads and fishing villages to make Reykjavik their new home. By 1920, 20% of the population resided there and an urban centre began to form. Social movements, pressure groups and businesses boomed, providing Iceland with a strong middle class and laying the groundwork for the activism to come.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Þorleifur Þorleifsson. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Þorleifur Þorleifsson. No edits made.

Modern Feminism in Iceland

Throughout the sixties and seventies, grassroots activism had begun to take hold as the primary method for promoting civil liberties and instigating social change.

In 1975, Icelandic women had grown tired of their lack of representation and inferior pay scales. With the UN having declared 1975 a ‘Women’s Year’, it was the radical feminist movement the Red Stockings who first proposed the idea of a strike, not only to commemorate the occasion but to finally make a statement. After some discussion between the various women’s rights organisation, a strike was finally agreed, though the word ‘strike’ would be replaced by ‘day off’. By making this change, the organisers hoped the rally would earn mass support and would also avoid having participants disciplined by their employers.

On the 24th October, approximately 90% of the female population went on their professional and domestic strike for the Woman's Day Off.

Instead of working their routine jobs, cooking family meals, rearing the children or housekeeping, 25,000 women took to the streets as a unified force demanding change. One of the protest’s ambitions was to prove how indispensable women are to the working life of Iceland’s economy.

Icelandic society immediately felt this absence. Fathers brought their children to the workplace (nurseries and schools were closed due to the lack of staff), the newspapers were unable to print (typesetters were almost always women), shops remained closed, telephone exchanges were left unanswered and even some radio broadcasts were forced to shut down.

Instead, downtown Reykjavik was filled with cheering, pots banging, whistles, protest signs. Within five years of the first Woman’s Day of Protest, Iceland had the world’s first democratically elected female head of state, President Vigdís Finnbogadóttir. The protest was so successful, in fact, that Iceland has kept up the tradition, hosting a Woman’s Day Off in 1985, 2005, 2010 and 2016.

- See also: Iceland did it first in the world

Icelandic women in Politics

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Rob C. Croes. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Rob C. Croes. No edits made.

Vigdís Finnbogadóttir held the position of President of Iceland for sixteen years, making her the longest serving female president from any country to date. A divorced single mother, her presidency took the world by surprise in the less liberally minded 1980s, with international headlines reading quite simply "WOMAN ELECTED PRESIDENT."

Though she was initially reluctant to run, Vigdis was soon convinced by her fellow countrymen to prove women could successfully run a campaign and win. Despite the fact she achieved only a narrow margin of a victory, her popularity quickly soared, securing her three later re-elections.

Adored by Icelanders the country over, Vigdís Finnbogadóttir is to this day very well aware that her victory came off the back of the 1975 Women's Day Off. Throughout her tenure as a President, she vigorously pursued the development of girl's education, coined the expression "never let the woman down" and acted a role model for young Icelandic women.

Outside of the Women's movement, she was a keen spokesperson for environmental issues and was instrumental in setting up the Reykjavik Summit, a crucial meeting held between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev in the 1980s that helped to bring a close to the Cold War.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Nationaal Archief. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Nationaal Archief. No edits made.

Vigdís Finnbogadóttir has not been the only woman to push the boundaries of leadership in Icelandic politics.

In 2009, Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir was elected as Iceland’s first female prime minister and, coincidentally, the world’s first openly gay head of state. She was instrumental in leading the charge against sexual violence and rape. Guðrún Jónsdóttir of Stígamót, a Reykjavik organisation campaigning against sexual violence, said of the prime minister, "Johanna is a great feminist in that she challenges the men in her party and refuses to let them oppress her."

Kolbrún Halldórsdóttir, a former MP with the Left-Green Movement, pushed to end stripping and lap dancing based on feminist ideals, rather than religious ones. At the time, she firmly told the national press, "It is not acceptable that women or people in general are a product to be sold."

As of 2010, strip clubs, prostitution and profiting off the nudity of employees have all been made illegal. This new law effectively meant that authorities were able to close in and shut down the major institutions facilitating human trafficking and the sex trade.

Other genders in Iceland

The gender equality in Iceland isn't limited to simply females and males. Iceland is also on the forefront of equality when it comes to the LGBTQIA community, so that individuals that identify as non-binary gender are as much a part of the society as anyone else.

Above you can see Ugla Stefanía Kristjönudóttir Jónsdóttir give a talk about non-binary gender and the obstacles they still face in society today, at a TEDx talk in Reykjavík.

Ugla is the former chairperson of Trans Iceland, a part of the '78 Association, Iceland's LGBTQIA rights group. As a transgender rights activist who prefers non-gendered pronouns, they write about genderqueer rights for Huffington Post, help to spread information about non-binary people, and aid genderqueer rights around the world.

While there is still progression to be made in terms of the recognition of trans and genderqueer individuals, Iceland allows platforms for these people to represent themselves freely. Discrimination on the basis of perceived or actual gender identity is illegal, and those who transition can change their names and genders on all legal documents without issue. This has been the case since the passing of sweeping progressive legislation in 2012, protecting the rights of those outside the binary.

While not perfect, Iceland is a much more welcoming place today to discuss alternative gender issues than it was when the first transgender person came out. In 1989, Anna Kristjánsdottir was forced to move to Sweden to receive any support at all. Since her return, she has become recognised as a pioneer for transpeople, and celebrated for her bravery.

- See also: Gay Iceland: All you need to know

- See also: A bit about gay Iceland

Gender Equality Today

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Helgi Halldórsson. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Helgi Halldórsson. No edits made.

There is still much to be done, of course. Only 22% of managers and 30% of televised experts in Iceland are women. Women still have less economic power than men, earning 14% to 18% less on average. Labour unions and equal right advocates are quick to point out that, effectively, wage disparity means women in Iceland stop earning before their male counterparts; given the scale of a year, women would stop earning a salary on November 10th. To put it another way, given the scale of one working day, women stop earning a salary at 14.53PM. This is the reality of wage disparity in 2017.

Sexual harrassment and domestic violence are still key areas that require focus. A 2015 survey also showed that almost half of the women working in the service industry have experienced sexual harassment of one kind or another. There has been significant progress made in the prosecution of domestic abusers however.

In 2015, 94% of cases reported to the police were dropped. One year later, this percentage has dropped to a remarkable 3%. This is largely down to the Keeping The Windows Open project, a UN side-mission that directly collaborates with the police. Recent legislation also means that domestic abusers, or those accused, can be removed from the household.

Statistics demonstrate that only a handful of rape victims report their crimes to the police and, from this, an even smaller number of convictions are made. In Iceland, there are two emergency rape wards for women who have suffered sexual violence. These wards are staffed by specialised nurses, psychiatrists and support staff, as well as a team of lawyers to provide legal assistance and a line of communication to the police and the courts.

There is also a woman’s shelter for women and children who have suffered violence at home. In 2015, approximately 400 women reached out to the shelter for help, of which 126 took refuge.

Besides the Soviet Union and Mexico, Iceland was the first nation to legalise clinical abortions - it was also the first not to retract that decision at a later date. Abortions were made legal in Iceland on the 28th January 1935, marking the way for a modern abortion legalisation policy.

The fight for progress is ongoing and uphill. In 2015, the Free The Nipple campaign took ahold of Iceland in support of a female student who revealed her nipple on her own Twitter page and was bullied by another student because of it. The campaign itself is focused on the double standards regarding the censorship of the female breast and the sexualisation of women's bodies. As they in 1975, men and women took to the streets of Reykjavik to make their voices heard.

Public breastfeeding is considered completely normal in Iceland, the best example perhaps being when an MP breastfed her baby during parliament in 2016 that made international headlines.

Women in sport get a lot of media coverage, and have many great supporters of both individuals that watch them compete and bigger companies that back them with funding.

Iceland's commitment to gender equality is as strong today as it has ever been. In 2015, Iceland celebrated 100 years of women having the vote.

- See also: 100 years of women voting

To continue forward, the Icelandic government ran a gender-equality conference aimed at only men, with the important message that their participation is also required to help solve prevalent inequalities. In 2016, the 40th anniversary of the gender equality law, the Alþingi made amendments to the existing legislation, handing down stricter punishments for domestic abuse and stalking.

There is still a lot of work left to be done, but Icelanders continue to lead the charge to full-scale gender equality, building a society that is just, fair and sets an international reputation.

Inne interesujące artykuły

Sylwester na Islandii

Jak wygląda Sylwester na Islandii? Jak wygląda Sylwester w Reykjaviku? Co sprawia, że Sylwester na Islandii jest wyjątkowy? Gdzie są najlepsze imprezy sylwestrowe w Reykjaviku? Dowiedz się wszystki...Czytaj więcej

Islandzcy Chłopcy Bożonarodzeniowi i Gryla | Islandzkie bożonarodzeniowe trolle

Kim są islandzcy Chłopcy Bożonarodzeniowi? Kogo świętuje się na Islandii w Boże Narodzenie, jeśli nie Świętego Mikołaja? Jaką rolę w islandzkim bożonarodzeniowym folklorze odgrywa olbrzymka Gryla i...Czytaj więcejLokalizacje filmowe na Islandii — Pełna lista

Jakie międzynarodowe filmy były kręcone na Islandii? Dlaczego hollywoodzcy producenci decydują się na kręcenie filmów na Islandii? Zapoznaj się z naszą pełną listą międzynarodowych wysokobudżetowych...Czytaj więcej

Pobierz największą platformę turystyczną na Islandii na telefon i zarządzaj wszystkimi elementami swojej podróży w jednym miejscu

Zeskanuj ten kod QR za pomocą aparatu w telefonie i naciśnij wyświetlony link, aby uzyskać dostęp do największej platformy turystycznej na Islandii. Wprowadź swój numer telefonu lub adres e-mail, aby otrzymać wiadomość SMS lub e-mail z linkiem do pobrania.