Being queer in Iceland isn't just accepted—it's celebrated. There are very few places in the world where people across the gender and sexuality spectrum receive as much love and encounter as little hate as they do in Iceland.

With legal equality, strong representation in parliament and the media, and an infrastructure to support and elevate queer people, Iceland has become a true rainbow paradise. Queer culture thrives in Iceland, making it a popular tourist destination for LGBTQ+ travelers.

Why You Can Trust Our Content

Guide to Iceland is the most trusted travel platform in Iceland, helping millions of visitors each year. All our content is written and reviewed by local experts who are deeply familiar with Iceland. You can count on us for accurate, up-to-date, and trustworthy travel advice.

Iceland is fast becoming recognized as a home away from home for the LGBTQ community. Many organizations today specialize in gay travel, the local scene is ever-developing, and a whole range of events cater specifically to queer people and allies.

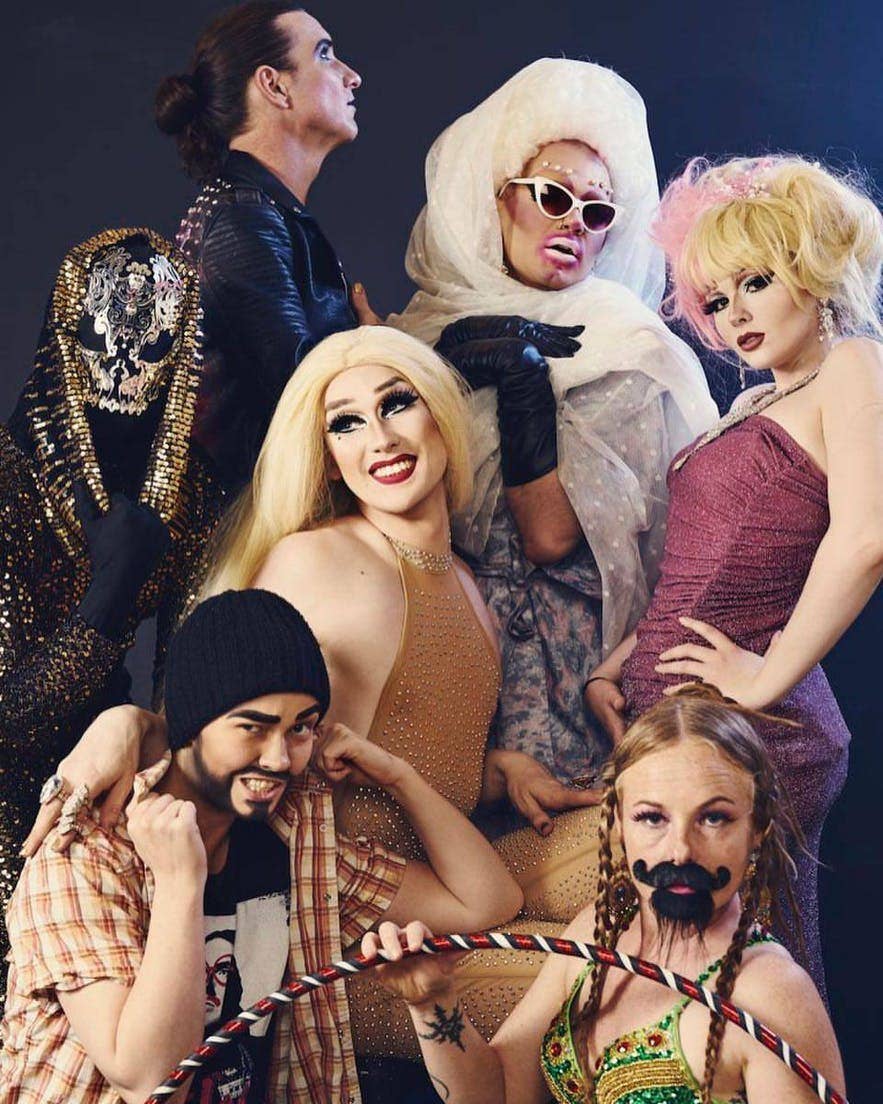

Reykjavik boasts a vibrant LGBTQ+ scene with inclusive bars and drag shows. Queer culture is deeply woven into the city’s identity, and Reykjavik walking tours often highlight key LGBTQ+ landmarks and hotspots. There are also plenty of LGBTQ+ friendly tours in Iceland to venture on. It's a welcoming, colorful destination where queer travelers feel truly at home.

So if you’re asking yourself, is Iceland gay friendly? The answer is a resounding yes. Read on to learn all about the LGBTQ+ scene in Iceland.

Key Takeaways

-

Iceland is extremely LGBTQ+ friendly, with legal equality, strong representation in society, and a culture of celebration.

-

Reykjavik has a thriving queer scene with events like Reykjavik Pride being very popular.

-

Visitors will find that accommodations in Iceland are LGBTQ+ friendly.

-

Dating and social interactions within the queer community are open and accepted in Iceland—particularly in Reykjavik.

- Acquaint yourself with the history of Gender Equality in Iceland

- Read more about Icelandic History

Life in Gay Reykjavik

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Helgi Halldórsson. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Helgi Halldórsson. No edits made.

There are many ways visitors can immerse themselves in Iceland’s queer scene. While there isn’t a specific Reykjavik gay neighborhood or entertainment district, the downtown neighborhoods have a higher concentration of LGBTQ events and destinations, including the historic 22 Bar and the famous Kiki Queer Bar.

It is very common for general institutions to display rainbow flags in their windows or to post signs warning patrons against any discrimination on their property. Almost every space in Reykjavik is a safe and comfortable environment.

It is partially due to this wide acceptance that there aren’t as many LGBTQ-specific restaurants, bars, and clubs.

Similarly, the Reykjavik Pride Festival has become an event the whole family can enjoy, no matter their gender or sexuality—and the turnout for the march is almost unbelievable.

Though there are only about 340,000 people in the entire country, almost 100,000 come to celebrate each year, including the nation's president. Pride Week hosts many events, such as concerts, documentary and film screenings, live comedy shows, and drag performances.

Up-and-coming queer artists are also given many platforms to perform. Regular performers on the downtown scene, such as Jonathan Duffy, a gay comedian, and Mighty Bear, a genderqueer punk musician, are becoming more and more known.

Up-and-coming queer artists are also given many platforms to perform. Regular performers on the downtown scene, such as Jonathan Duffy, a gay comedian, and Mighty Bear, a genderqueer punk musician, are becoming more and more known.

Reykjavik Kabarett and Gaukurinn are also incredible platforms for queer talent and are very popular among the queer audience. Iceland’s drag scene is particularly of note for its diversity, with drag kings and genderqueer performers as beloved as the more traditional queens.

- See also The Drag Scene in Iceland

Best Gay Bars and LGBTQ+ Nightlife in Reykjavik

Reykjavik has become known for its nightlife in recent years, and the Reykjavik gay scene is no exception. While there are relatively few gay bars in Iceland, there are plenty of opportunities to dance the night away with diverse groups of partiers all over the city.

Reykjavik has become known for its nightlife in recent years, and the Reykjavik gay scene is no exception. While there are relatively few gay bars in Iceland, there are plenty of opportunities to dance the night away with diverse groups of partiers all over the city.

Kiki Queer Bar

Kiki is the hottest gay club in Reykjavik, located on Laugavegur Street—it’s an address synonymous with many of Reykjavik's past gay bars. The DJs mostly spin disco, Eurovision, and chart-topping pop, and its colorful atmosphere makes it the perfect place to party until the wee hours of the morning. You can't miss its rainbow-color facade.

Kiki is the hottest gay club in Reykjavik, located on Laugavegur Street—it’s an address synonymous with many of Reykjavik's past gay bars. The DJs mostly spin disco, Eurovision, and chart-topping pop, and its colorful atmosphere makes it the perfect place to party until the wee hours of the morning. You can't miss its rainbow-color facade.

Opening Hours:

-

Thursday: 8 PM–1 AM

-

Friday–Saturday: 8 PM–3:30 AM

Address: Laugavegur 22, 101 Reykjavik

22 Bar

Just beneath the Kiki Queer Bar is a queer-friendly bar and cafe—22 Bar. With its easygoing atmosphere, the restaurant is dedicated to providing a safe space for the LGBTQ community.

Classic tunes play from the well-curated vinyl record collection in their rustic and cozy listening stations. It’s the perfect place to unwind with drinks and light meals.

Opening Hours:

-

Daily: noon–1 AM

Address: Laugavegur 22, 101 Reykjavik

Gaukurinn

Gaukurinn is an inclusive dive that serves as home to Iceland’s drag scene and most of Reykjavik’s underground and alternative arts. The venue’s calendar is filled with comedy, karaoke, live music, movie nights, and delicious all-vegan food.

Whether visitors are looking for a heavy metal show, an electronic dance party, or a fun movie screening, the venue has become more than a gay bar. It’s a haven for all.

Opening Hours:

-

Friday–Saturday: 5 PM–3 AM

-

Sunday–Thursday: 5 PM–1 AM

Address: Tryggvagata 22, 101 Reykjavik

Gay Dating in Iceland

It is not at all uncommon to see two men or two women holding hands down the high street, having a romantic meal in one of the city’s restaurants, or dancing as inappropriately as opposite-sex couples do after too many drinks on a night out.

It is not at all uncommon to see two men or two women holding hands down the high street, having a romantic meal in one of the city’s restaurants, or dancing as inappropriately as opposite-sex couples do after too many drinks on a night out.

As with anywhere in the world, ignorant people exist, and, of course, there is no guarantee that same-sex couples will be free from harassment. In the accepting culture of Reykjavik, however, bigotry is rare and not tolerated by the general populace.

In general, there are few taboos when it comes to dating in Iceland. Icelandic people are usually very sex-positive and do not tend to stigmatize anyone for their sexual behavior. Many single Icelanders use dating apps, and the queer community is no exception.

Most popular international apps, like Tinder, Grindr, and ROMEO, are just as popular in Reykjavik, but Iceland also has it's own dating app, Smitten, which is very popular. If you’re staying in town for long, remember that gay Reykjavik is a pretty small scene, so get used to seeing the same faces.

While most of the nation is socially progressive, the rural areas are so sparsely populated that you may not see another queer person on an app within a hundred kilometers once outside Reykjavik.

One thing to keep in mind is that there are growing concerns in Iceland about the rising rates of STI transmission, so if you are looking for a romantic encounter, stay safe.

- Read Sex and Nudity to find out more about Iceland's sex-positive attitudes

Plan the Perfect LGBTQ+ Trip to Gay Iceland

Planning your gay getaway to Iceland? You're in luck. Reykjavik is a welcoming city with plenty of options for LGBTQ travelers. From choosing the right accommodations to exploring the vibrant queer scene and participating in special events, we've got you covered.

Planning your gay getaway to Iceland? You're in luck. Reykjavik is a welcoming city with plenty of options for LGBTQ travelers. From choosing the right accommodations to exploring the vibrant queer scene and participating in special events, we've got you covered.

LGBTQ+-Friendly Hotels in Reykjavik

Reykjavik’s accommodations and other hotels, hostels, and guesthouses in Iceland are welcoming to all, but these are a few hotels in Reykjavik that have proven to be reliably accepting and accommodating.

Reykjavik’s accommodations and other hotels, hostels, and guesthouses in Iceland are welcoming to all, but these are a few hotels in Reykjavik that have proven to be reliably accepting and accommodating.

Konsulate

Plus, it's central—close to the harbor and loads of must-see locations. They're totally welcoming to everyone, especially LGBTQ+ folks, with a really relaxed and inclusive atmosphere.

You'll also be near Austurvollur Square, a hub for Reykjavik's LGBTQ scene, packed with cafes and restaurants. It's a great place to kick off your adventures in this open and diverse city.

Sand Hotel

Sand Hotel in Reykjavik is a welcoming, gay-friendly hotel situated in the city center, just off the hopping Laugavegur Street. This central location provides easy access to numerous shops, restaurants, and nightlife options. Several LGBTQ venues, such as Kiki Queer Bar, are within a comfortable walking distance from the hotel.

Sand Hotel is an excellent choice for those seeking a boutique hotel in central Reykjavik. Its prime location offers plenty of attractions—a variety of museums, restaurants, cafes, and shops are all conveniently located within walking distance.

For a stylish, modern design, a sophisticated atmosphere, and excellent customer service, Sand Hotel is a strong recommendation.

Storm Hotel

Storm Hotel is a modern and stylish place to stay located at Thorunnartun 4, Reykjavik, just a short walk from key attractions like Hofdi House and Laugavegur Street, known for its LGBTQ-friendly bars and restaurants. The hotel offers chic accommodations with modern amenities, including a trendy bar.

Storm Hotel is a modern and stylish place to stay located at Thorunnartun 4, Reykjavik, just a short walk from key attractions like Hofdi House and Laugavegur Street, known for its LGBTQ-friendly bars and restaurants. The hotel offers chic accommodations with modern amenities, including a trendy bar.

LGBTQ visitors will find the hotel’s inclusive atmosphere a welcoming place to stay, with easy access to the city’s vibrant culture and diverse nightlife.

Alfred's Apartments

Each apartment features a fully equipped kitchen, private bathroom, and free Wi-Fi. Guests can choose from studios or one-bedroom units, some with balconies or sea views.

The location is ideal for exploring Reykjavik's vibrant queer scene, shops, restaurants, and nightlife. The apartments include amenities such as a smart TV and laundry facilities, and they are close to Bus Stop 9—Snorrabraut—for airport transfers.

Alfred's Apartments provides a comfortable and inclusive stay for all guests, including LGBTQ travelers.

LGBTQ-Specific Tourism in Iceland

As inclusive as general Icelandic culture and tourism are of LGBTQ+ visitors, it’s still nice to find communities specifically built around the LGBTQ+ community. Here are some of the most popular events and tours:

As inclusive as general Icelandic culture and tourism are of LGBTQ+ visitors, it’s still nice to find communities specifically built around the LGBTQ+ community. Here are some of the most popular events and tours:

Reykjavik Bear

Reykjavik Bear is an annual festival that began locally but has slowly grown to include a few dozen international visitors each year. The celebration of the local bear community is held at the end of August in Reykjavik.

Originating in 2019 from the legacy of the Bears on Ice festival, RVKBear has grown significantly, attracting over 120 attendees in 2024. The 2025 event marks its fifth anniversary and the 20th anniversary of the inaugural Bears on Ice festival.

Reykjavik Bear will return in 2026, taking place from September 3 to 6 and continuing its tradition of bringing together the local and international bear community in Reykjavik.

Reykjavik Pride

While Pride Month is officially recognized in June, the Reykjavik Pride festivities typically occur at the beginning of August. Established in 1999, the festival has grown from a modest gathering into one of Iceland's largest annual events, attracting over 100,000 attendees.

While Pride Month is officially recognized in June, the Reykjavik Pride festivities typically occur at the beginning of August. Established in 1999, the festival has grown from a modest gathering into one of Iceland's largest annual events, attracting over 100,000 attendees.

The festival's centerpiece is the Pride Parade, a lively procession through Reykjavik's streets, showcasing colorful floats, performances, and messages advocating for LGBTQ rights. The parade route typically winds through central Reykjavik, culminating in a grand outdoor concert at Hljomskalagardur Park.

For LGBTQ visitors, attending Reykjavik Pride offers an opportunity to experience Iceland's inclusive culture and connect with a global community in a festive atmosphere.

The event celebrates diversity and underscores Reykjavik's commitment to human rights and equality, making it a compelling destination for travelers seeking celebration and cultural enrichment.

LGBTQ City Tour

Starting at Ingolfstorg Square, the tour is led by knowledgeable local guides and offers an intimate exploration of Reykjavik's vibrant community, blending iconic landmarks with insights into the city's LGBTQ scene.

Guests will see the Hallgrimskirkja Church, the Sun Voyager sculpture, and the Harpa Concert Hall, with guides sharing stories of the culture’s influence on literature, music, and politics.

An engaging aspect of the tour is the focus on prominent LGBTQ Icelanders, offering a personal perspective on the community's impact within the city. The experience is designed to be inclusive and accessible, and limited to 12 participants.

Reykjavik City Card

The Reykjavik City Card offers visitors an affordable and flexible way to explore Iceland's capital. This card provides free entry to numerous museums and galleries, unlimited access to all Reykjavik geothermal swimming pools, and unrestricted travel on city buses within the Reykjavik capital area. You can get a 24 hour card, or ones valid for 48 hours or 72 hours for more time.

Additionally, it includes complimentary ferry rides to Videy Island and discounts at selected restaurants, shops, and on various tours and services.

For LGBTQ travelers experiencing Reykjavik, the city card enhances the experience of visiting several inclusive and welcoming attractions.

History of Gay Iceland

Iceland has not always been a sanctuary for queer people. The fight for equality here was as much of an uphill struggle as it was, and is, in the rest of the world.

Iceland has not always been a sanctuary for queer people. The fight for equality here was as much of an uphill struggle as it was, and is, in the rest of the world.

The island’s isolation and the influence of conservative religious institutions meant LGBTQ relationships were demonized well into the 20th century.

During the invasion of Iceland in World War II, British and American forces were here in numbers that rivaled the native male population. This influx of worldly men from exotic places did not go unnoticed by Icelandic women, and their interest alarmed the local men.

Both women who took American partners and their children met a tremendous amount of discrimination. The same discrimination extended to Iceland lesbian communities and gay Icelandic men.

The first well-known gay man to come out was the beloved singer and theater personality Hörður Torfason. He encountered such a change in public opinion toward him that he exiled himself from the nation for 15 years. Iceland’s first openly transgender woman, Anna Kristjánsdottir, met similar discrimination and ridicule when she first came out.

In only a single generation, these attitudes changed. Both Hörður and Anna have since returned to Iceland and are now celebrated for their bravery rather than hated for their differences.

Gay Life in Iceland Today

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by JP. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by JP. No edits made.

After Hörður Torfason came out to a hostile nation, members of the community felt emboldened to come out. In 1978, the National Queer Organization was formed, know as Samtökin ‘78 in Icelandic, and it sparked the liberation movement.

With greater visibility than ever before, more and more Icelanders started to come out. With such a small population, it was just a matter of years before most Iceland locals realized they knew members of the LGBTQ Iceland community.

Attitudes changed quickly, and Iceland LGBTQ laws followed suit.

-

Since the 1990s, a slew of legislation has been passed, making Iceland one of the most gay-friendly places on Earth.

-

Iceland was one of the first European countries to recognize same-sex partnerships in 1996 and to grant equal adoption and IVF rights for same-sex couples in 2006.

-

A 2004 IMG Gallup poll showed 87% of Icelanders surveyed declared support for same-sex marriage. In the same year, a US poll on same-sex marriage showed less than half—just 42%—of Americans believed the same.

-

Iceland became the first nation with an openly gay leader—Jóhanna Sigurðardottir was elected Prime Minister in 2009.

-

In 2010, same-sex marriages were made legal in Iceland.

-

In 2012, the trans and genderqueer communities saw sweeping legislation that formalized the name and identity-changing processes.

-

In 2015, when the Church of Iceland declared that priests could not deny marriage based on sexual orientation.

-

In 2019, Iceland passed the Gender Autonomy Act, a groundbreaking law that allows individuals to legally change their gender. The law introduced a third gender option (“X”) on official documents and protects intersex children from non-consensual medical interventions unless medically necessary.

While there is still progress to be made, almost everyone is on board to help make it happen.

Queer Community in Iceland

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Helgi Halldórsson. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Helgi Halldórsson. No edits made.

Today, Iceland’s queer population is thriving. The National Queer Organization is stronger than ever, providing community outreach every weekday and free counseling for those navigating their identity.

While the National Queer Organization is largely in place for locals, visitors to Iceland looking to learn about the gay scene have several organizations they can turn to.

Gay Iceland is a go-to site for discovering what is happening in gay Reykjavik, and Gay Ice is a popular gay travel guide.

Since 2011, there has even been a tour-guiding company catering specifically to the LGBTQ community, Pink Iceland. Pink Iceland became known across the world in 2019 when they contributed a prize to Rupaul’s Drag Race All Stars 4; two queens were granted holidays to Iceland for winning the makeover challenge.

The Future of Gay Iceland

In a world where civil and human rights are looking less secure in many places, it can be said with refreshing certainty that the support of queer people in Iceland is not going away anytime soon. This celebration of diversity is now part of the national character and is held with deep pride among the majority of Icelanders.

In a world where civil and human rights are looking less secure in many places, it can be said with refreshing certainty that the support of queer people in Iceland is not going away anytime soon. This celebration of diversity is now part of the national character and is held with deep pride among the majority of Icelanders.

Queer people fit perfectly within this nation’s growing reputation as a bastion of creativity and forward-thinking. For anyone seeking to be themselves, celebrate their identity, and have no fear of doing so, there really is no better place in the world than Iceland.

Ready to Experience Iceland’s LGBTQ+ Scene?

Iceland is one of the most inclusive and welcoming travel destinations for the LGBTQ+ community, and we hope this guide has inspired you to explore it for yourself. When you’re ready to plan your trip, browse the widest selection of vacation packages in Iceland to find one that works for you.

Iceland is one of the most inclusive and welcoming travel destinations for the LGBTQ+ community, and we hope this guide has inspired you to explore it for yourself. When you’re ready to plan your trip, browse the widest selection of vacation packages in Iceland to find one that works for you.

Is there a gay scene in Iceland?

Does Iceland have gay marriage?

Are there specific LGBTQ+ bars or clubs in Reykjavik?

When is Reykjavik Pride?

Is it safe for LGBTQ+ couples to show affection in public?

What legal rights do LGBTQ+ people have in Iceland?

What is the general attitude toward LGBTQ+ travelers in Iceland's rural areas?

Is there anything we missed in our guide? Have you visited Iceland before? Share your own experiences as an LGBTQ+ traveler in Iceland in the comments below.