The Ultimate Guide to Turf Houses in Iceland

- What is an Icelandic Turf House?

- The History of Turf Houses in Iceland

- Turf Churches in Iceland

- Most Popular Turf Houses in Iceland

- 1: Arbaer

- 2: Arngrimsstofa

- 3: Austur-Medalholt

- 4: Brattahlid & Bergsstadir

- 5: Bustarfell

- 6: Eiriksstadur

- 7: Glaumbaer

- 8: Graenavatn

- 9: Grenjadarstadur

- 10: Keldur

- 11: Laufas

- 12: Nyibaer

- 13: Reynistadur

- 14: Selid

- 15: Skogar Turf Houses

- 16: Storu-Akrar

- 17: Thvera

- 18: Thjoveldsisbjaerinn Strong

- 19: Tyrfingsstadir

What are Icelandic turf houses? How were they built, what were they like to live in, and when did they stop being used? Are there any historical turf houses left in Iceland, and where can you find them? Continue reading for the ultimate guide to turf houses in Iceland.

- Find the Widest Selection of Tours on Offer in Iceland

- Check of this article on the History of Icelandic Architecture

Photo by Pierre-Axel Cotteret

Photo by Pierre-Axel Cotteret

For a country settled in 930 AD and inhabited ever since, you may have noticed that Icelanders have very few historic buildings of note. While most other European states have castles and ruins that date back eons, you’ll be hard-pressed to find anything built before the 19th Century in Iceland.

The reason for this is that the vast majority of Iceland’s buildings were made to be disposable. With an extreme and fickle climate, a lack of decent building materials, virtually no infrastructure and the poverty of the people themselves, early Icelanders had to be creative when constructing their homes. As such, the Icelandic turf house was born.

- See also: The History of Iceland

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

These buildings are some of the only relics that paint a vivid picture of what Iceland was like before it became the modern, trendy tourist hub that it is today. For historians, these sites are essential to the story of Iceland; to the locals, they are reminders of the hardships and tenacity of their ancestors.

To guests, however, turf houses are incredible places to learn about this country’s fascinating past and culture. When coming to Iceland, most visitors neglect this side of the nation in favour of its awesome nature. A visit to a historic turf house, however, will show you why it is such a mistake to do so.

What is an Icelandic Turf House?

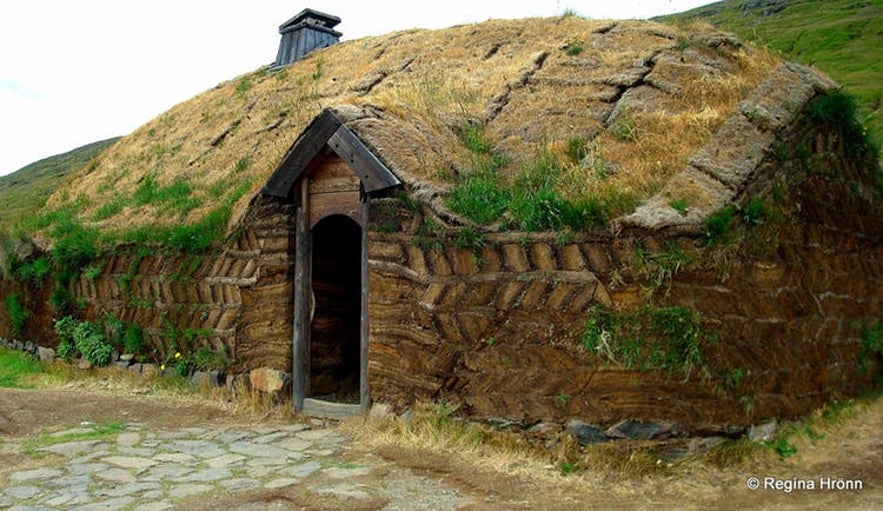

Turf houses are, quite simply, semi-underground abodes with a grassy roof, not unlike the Hobbit homes in Lord of the Rings.

They were built by stacking flat stones to create the foundation, using birch or driftwood to create frames, then covering the structure with several layers of turf. A door would mark the entrance, and there were occasionally small windows (although few made of glass, a rare commodity). On the roof, there would usually be a small hole for ventilation, which could be closed in bad weather with a lid made of animal guts stretched over a barrel ring.

Though it was true that Iceland was covered in birch forests when first settled, Icelandic birch was pretty useless in building anything more than the aforementioned frames and door. Turf, however, was known to be insulating by the Norwegians when they arrived and was adopted as a primary material for houses pretty much immediately.

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

The appearance and architectural style of turf houses went under several changes throughout history. Initially, most resembled classic Viking longhouses, complete with saunas. As Icelanders burnt through the nation’s forests and an ensuing mini Ice Age prevented more from growing, they changed into networks of smaller buildings, connected with underground tunnels.

In the 18th Century, it became more popular to have wooden ends at both sides of a turf house, and a gable-style entrance. Almost all intact turf houses in Iceland today were built in this fashion.

Turf houses provided the best insulation possible, but that does not mean they were comfortable. They were so damp that fresh produce would quickly rot; they filled with smoke whenever someone cooked; they were dark, especially in winter; and they stank, being where everyone ate, slept, socialised and did their indoor work. They were also often crowded, housing the whole family in addition to farmhands, seasonal workers, vagrants and potentially state dependents, and everyone usually slept in one room.

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Turf houses also required constant maintenance, being made mainly of organic material and constantly exposed to the elements. Neglecting household duties could easily result in their collapse. As such, it was widespread for them to be abandoned every year, and a new one built in another location.

Because of how disposable they were and how quickly they were deserted, few turf houses have made it to the modern era without significant structural damage.

The History of Turf Houses in Iceland

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

As mentioned, turf houses were the homes of Icelanders from the very beginning. They were common in Norway at the time, and not only did the first settlers know how to make them, but Iceland had an abundance of the materials required for their construction.

Due to the country’s geographical isolation, as well as the pressing thumb of its Danish colonisers, the way of life in an Icelandic turf house changed little over the centuries. Besides developments in the architectural style, the people continued to live simple lives underground in these sodden, uncomfortable structures, as the rest of Europe left the Middle Ages and headed towards Industrialisation.

There really was no other option. A few Icelanders lived in natural fortresses such as Borgarvirki or in stone huts for the fishing season, as can be found at Selatangar, but other than that, the only shelter to be found was in caves. These were inhabited only by the extremely impoverished, or else outlaws who were not allowed back into civil society, and were extremely dangerous to live in.

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

It would not be until the 20th Century that the Icelandic turf house stopped being the norm; the technologies of the industrial era were very slow to reach Iceland. When they did, they largely found themselves in the hands of the more affluent, who could then produce goods and services at such rates that it made poor farmers and fishermen significantly poorer.

As such, there was an exodus from the countryside to the larger settlements - namely Reykjavík. The majority of people sold their farms, gathered their possessions, and abandoned their turf houses. Without maintenance, these historic homes were largely destroyed by the elements within years. For the majority, this was a relief; the turf house represented a lifestyle of hardship and poverty in the modernising world, so who would care if they fell into disrepair?

As it would turn out, the next generation of Icelanders. By the 1960s, the vast majority of people had moved into what we would consider ‘normal’ accommodation, yet many still alive had grown up in a turf house. The fact that nature had so easily reclaimed most of these structures, which existed in living memory, left a tear in the fabric of Icelandic history. As such, a movement began to protect them.

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

The National Museum had, in fact, already been taking over turf houses for three decades, working to preserve them as they more and more became part of the past. Private landowners worked with them and other museums to have those on their property restored, and learning how to build and repair turf houses became somewhat of a respected craft.

As such, while the vast majority of these structures were lost to history, many remain dotted around the country. Some can be found in popular tourist locations such as the Lake Mývatn area and Skógar Museum, others in far-flung spots far from the crowds.

Their preservation is a top priority amongst many in the country, who consider them an essential part of Iceland’s story.

Turf Churches in Iceland

Turf was not just used to build homes in Iceland; it was also used to build churches. Iceland has historically been a devoutly religious country, and even today has more churches per capita than any other country. They were the centre of their communities, a place where people would come to pray, socialise, celebrate and mourn.

There are five original turf churches left in Iceland, most in the north of the country; a reconstructed one can also be found in Reykjavík.

- See also: Reykjavik Guide

Most Popular Turf Houses in Iceland

Although most turf houses were enveloped back into nature in the 19th and 20th Centuries, many have been preserved and can still be visited by guests. Some of these have great historical importance, having been home to notorious chieftains, while others have a great cultural significance today, having reopened as museums.

Below is a list of nineteen historic turf houses you can visit on your travels in Iceland, listed in alphabetical order. Omitted from this list are those that are closed to visitors and ones that have only been built recently.

For even more information and photos, check out A List of the Beautiful Turf Houses in Iceland, which will provide you links to blogs detailing Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir's travels to each one.

1: Arbaer

The very first turf house on this list is by far the easiest to visit for the vast majority of guests coming to Iceland. Árbær turf house is located conveniently in Reykjavík, and is part of the Árbær Open Air Museum.

The Árbær Open Air Museum has twenty buildings in total, which tell the fascinating story of how Reykjavík turned from sparse farmland to a capital city. Costumed guides and countless artefacts make a trip here an interesting way to visualise Iceland’s history, particularly if travelling with children.

The museum is especially worth visiting over Christmas, where it becomes a winter wonderland overflowing with festive spirit.

Historians believe that there may have been a turf house on this site since 1226 based on written records, although more concrete evidence date it back to 1464.

- See also: Christmas in Iceland

2: Arngrimsstofa

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

North Iceland has more turf houses than the rest of the country, in all different shapes and sizes. Arngrímsstofa is particularly notable due to the fact that it is one of the smallest, being just five metres squared.

Arngrímsstofa dates back to 1884, and was built by local folk artist Arngrímur Gíslason. It was later rebuilt in 1983 to honour a past president, Kristján Eldjárn. Like most turf houses in Iceland, it is owned by the National Museum and open to guests.

3: Austur-Medalholt

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Austur-Meðalholt is a set of eight privately owned turf buildings in South Iceland that are renowned for the museum within them. The owners have a wealth of photos and artefacts depicting what life was like for Icelanders living in such houses, and they will be happy to show you around.

The current buildings on the site date back to 1895, but there have been turf houses here for the past 400 years. Austur-Meðalholt was abandoned in 1965 before it was bought by the new landowners and restored.

4: Brattahlid & Bergsstadir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

To feel the air of abandonment and to witness nature reclaiming a turf home, there is no better site than Brattahlíð and Bergsstaðir in Svartárdalur valley, North Iceland. Having been deserted in 1978 and claimed by no individual or institution since, they are slowly crumbling into the landscape around them.

Brattahlíð and Bergsstaðir are not the best example of historic turf houses, being built from 1904 to 1905 in quite a modern style, but they are one of the best places to visualise the literal collapse of this way of life.

5: Bustarfell

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Bustarfell is a premiere turf house in East Iceland, as it is notably large, boasts beautiful surroundings, and has a fascinating history. The site it is on had been first settled in 1532, and the building itself was constructed in 1770, making it one of the oldest turf houses in Iceland.

Bustarfell was deserted quite late compared to many other turf houses in Iceland, and well within living memory; the last residents left in 1966. The turf house now belongs to the National Museum.

6: Eiriksstadur

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Eiríksstaðir is a turf house in Iceland that has been built to resemble to longhouse of Erik the Red, the notoriously violent Viking who stumbled upon Greenland. Despite the fact that this turf house was only reconstructed recently, it earns its place on this list because of its proximity to the actual excavated ruins of the original building and its attention to detail.

At Eiríksstaðir, you can expect staff dressed in historical attire, willing to dress you like a Viking, provide traditional Ieclandic food, and let you handle props from the era, such as swords and shields. They are also very well informed regarding the country’s history, particularly the adventures of Eric the Red and his son Leif the Lucky.

Eiríksstaðir is located in west Iceland.

- See also: The Most Infamous Icelanders in History

7: Glaumbaer

Glaumbær, in Skagafjörður, North Iceland, is one of the most historically important sets of turf houses in the country; people have lived on-site since the Settlement Era. It is mentioned in many pieces of Iceland’s literature due to the fact that several renowned chieftains lived or stayed here.

There are 14 houses at Glaumbær; though most of the structures were built in the mid-19th Century, parts date back a century more. The farm was inhabited until 1947 and quickly taken over by the National Museum.

8: Graenavatn

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Grænavatn is a turf house located in the Lake Mývatn Area in North Iceland, owned by the National Museum of Iceland. It has a much more modern style than most other turf houses in the country, having been built in 1913, and its architecture reflects the transition at the time to a more comfortable way of life.

Adjacent to the house is a 150-year-old turf barn that contrasts quite dramatically with it. It is built in the traditional style, buried somewhat into the earth and covered in sod.

9: Grenjadarstadur

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Grenjaðarstaður is another turf house in North Iceland that has existed in one form or another since settlement. The current residence on site was built back in 1865, and it was deserted in 1949.

Since its abandonment, Grenjaðarstaður was bought by the National Museum. Today, the stable functions as a service centre for tourists, allowing you to both explore the interior of a turf building as you make plans for the rest of your trip. The museum is open in the summer time.

- See also: Travel Information in Iceland

10: Keldur

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Keldur, in South Iceland, is a turf farm that dates back to the Icelandic Civil War in the Age of Sturling, a few centuries after settlement. While evidence regarding the history of other turf houses comes largely from written sources, Keldur has archaeological evidence, with an underpass that was built as early as the 11th Century.

Owned by the National Museum, Keldur can be visited in summer. Like many other turf houses and farms, it has been reborn as a museum.

- See also: Where Do Icelanders Come From?

11: Laufas

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Steve L. Martin. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Steve L. Martin. No edits made.

Laufás is a turf farm located in Eyjafjorður, North Iceland. It has been inhabited, in different forms, for over a millennium, known for the fact that it is mentioned in the Book of Settlement. The current buildings on site were built between 1866 and 1877, and it has been owned by the National Museum since 1948.

Laufás has also been converted into a museum.

12: Nyibaer

Nýibær is a unique turf house due to the fact that it is unfurnished. Most turf houses now serve a secondary purpose (as a museum, gallery, or service centre), and are usually at least decorated in line with historical Icelandic traditions. To witness one completely empty is an experience that can help put into perspective how basic these structures were.

Nýibær was built in 1860, abandoned in 1945, and opened to the public by the National Museum in 1958. It is free to enter, and located in Hólar, North Iceland.

13: Reynistadur

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Reynistaður has been inhabited since the 10th Century, and like Glaumbær, was known to be the home of some significant chieftains. In 1935, however, the turf farm on site here was largely torn down with little regard for the history, leaving only a turf gable behind.

This gable, however, is particularly beautiful and well worth a visit, built in the architectural style of the Middle Ages and adored with artefacts from this period. It can be found in Skagafjörður, North Iceland.

14: Selid

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Though a relative young turf house, having been built in 1912, Selið has been perfectly restored by the National Museum, and boasts an unmatched location near the Skaftafell Nature Reserve, in South Iceland. This area was once a National Park in its own right due to its incredibly diverse beauty, with waterfalls, glaciers, lagoons, lava fields and forests, and is now part of the greater Vatnajökull National Park.

There are fewer turf houses in the south than the north, and no similar buildings in the area, making a visit to Selið a great opportunity for those only visiting this region of Iceland.

15: Skogar Turf Houses

Another great place to witness turf houses in South Iceland is at Skógar, where they form part of the local Cultural Heritage Museum. This attraction is, in fact, three museums in one, with a folk museum, open-air museum and technical museum, and boasts over 16,000 artefacts.

The turf houses on-site are great examples of what such structures looked like, but are reconstructions moved from other locations. Even so, many of their parts date back to 1830. Visiting the museum and turf houses is easy to do due to their proximity to the other sites of the spectacular South Coast, particularly Skógafoss waterfall.

16: Storu-Akrar

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Another example of a turf farm in Skagafjörður, North Iceland, is Stóru-Akrar. Originally built in 1745, the turf buildings here have been regularly maintained, making them some of the best-preserved examples of architecture from the 18th Century.

Stóru-Akrar is owned by the National Museum. It is also renowned for being close to the home of Helgi Sigurðsson, an expert in the old ways of constructing Icelandic turf houses.

17: Thvera

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Þverá is a set of nine turf houses, which can be found in Laxárdalar valley in North Iceland. This site is located off the beaten track and thus overlooked by most visitors, making it a perfect destination for those looking to avoid the tourist crowds. It is also blended beautifully into its natural surroundings, with a creek channelled through one of the buildings.

Built between 1849 and 1851, Þverá was inhabited well into the 20th century, until 1964. It has since been taken over by the National Museum. Though Þverá can occasionally be entered, their delicate structures sometimes mean that they can only be admired from the outside.

18: Thjoveldsisbjaerinn Strong

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Þjóðveldisbærinn Strong is a reconstructed turf longhouse in south Iceland, built in the style of the earliest Icelanders; it is the best place in the country to experience house the first settlers lived. The house it is based on is thought to have been destroyed in an eruption at Hekla 1104, and within it is a museum of crafts and objects from the time. Though somewhat of an outlier on this list due to the fact it was built recently, it retains its historical importance with its attention to detail.

Everything about Þjóðveldisbærinn Strong is designed to be as authentic as possible, with even the furniture and doors designed in accordance with the style of the 12th Century. Staff on site dress in traditional, period attire, and are experts on the history of Iceland.

19: Tyrfingsstadir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Tyrfingsstaðir is a private turf farm in Skagafjorður, North Iceland, with five turf houses and five turf outhouses. Built in 1870, the site is preserved excellently, and a classic representation of the architecture at the time.

Tyrfingsstaðir was abandoned relatively late, in 1969, before being bought and restored. Though you cannot enter the buildings here, you are welcome to admire them from the outside.

Inne interesujące artykuły

Nie zachowuj się jak Justin Bieber na Islandii!

Justin Bieber przyleciał na Islandię, aby nakręcić teledysk “I’ll show you” w 2015 roku. Efekty możesz obejrzeć powyżej. Pomimo tego, że Bieber zakochał się w wyspie i postanowił wrócić na Islandię...Czytaj więcejAkureyri, stolica północnej Islandii | Kultura, historia i pomysły na spędzenie czasu

Zdjęcie: Ludovic Charlet Jaka jest historia Akureyri, drugiego co do wielkości miasta na Islandii, które bywa nazywane północną „stolicą” kraju? Ile osób obecnie tam mieszka i jakie atrakcje można...Czytaj więcejSylwester na Islandii

Jak wygląda Sylwester na Islandii? Jak wygląda Sylwester w Reykjaviku? Co sprawia, że Sylwester na Islandii jest wyjątkowy? Gdzie są najlepsze imprezy sylwestrowe w Reykjaviku? Dowiedz się wszystki...Czytaj więcej

Pobierz największą platformę turystyczną na Islandii na telefon i zarządzaj wszystkimi elementami swojej podróży w jednym miejscu

Zeskanuj ten kod QR za pomocą aparatu w telefonie i naciśnij wyświetlony link, aby uzyskać dostęp do największej platformy turystycznej na Islandii. Wprowadź swój numer telefonu lub adres e-mail, aby otrzymać wiadomość SMS lub e-mail z linkiem do pobrania.