Charting the evolution of architecture in Iceland requires an understanding of a people in a constant tug-of-war with nature. For centuries, the island’s lack of traditional timber led residents to build with the earth itself, resulting in the iconic turf houses that define the early landscape and draw visitors on self-drive tours in Iceland.

Why You Can Trust Our Content

Guide to Iceland is the most trusted travel platform in Iceland, helping millions of visitors each year. All our content is written and reviewed by local experts who are deeply familiar with Iceland. You can count on us for accurate, up-to-date, and trustworthy travel advice.

Today, those ancient silhouettes have transformed into sleek, glass-and-steel landmarks that mirror the country's glaciers and basalt columns. In Reykjavik, this shows up as a mix of colorful corrugated iron and bold concrete, reflecting the city’s growth from a modest trading post into a modern Nordic hub.

This transformation is evident along the routes explored in Reykjavik walking tours, where visitors see firsthand how the “Cement Age” eventually gave way to contemporary structures such as Harpa Concert Hall.

Icelandic architecture celebrates resilience, creativity, and a deep connection to the natural world. This guide highlights the most iconic Icelandic buildings you can visit today, from historic turf houses to the modern marvels of Reykjavik.

Icelandic Architecture: Key Takeaways

-

The use of turf as a building material reflects early Icelanders’ ingenuity in a land where timber was scarce.

-

Modern Icelandic architecture draws inspiration from the island’s volcanic landscapes and natural environment.

-

The arrival of stone, corrugated iron, and cement transformed Reykjavik from a modest trading post into a thriving Nordic city.

-

Architects like Guðjón Samúelsson, Rögnvaldur Ólafsson, and Einar Sveinsson shaped a distinct Icelandic architectural identity by adapting foreign styles to local conditions.

-

Modern Icelandic architecture uses geothermal heating, durable materials, and minimalist forms to blend seamlessly with dramatic landscapes.

-

Landmarks like Hallgrimskirkja, Harpa, and Glaumbaer showcase Iceland’s history, resilience, and innovative spirit.

From The Settlement Era: Turf Houses & Longhouses

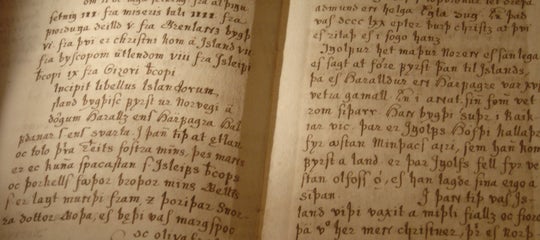

From the Age of Settlement until the early 20th century, turf houses defined Icelandic architecture. These homes were essentially timber structures modeled on longhouses from Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and the Scottish Isles, adapted to Iceland’s harsh climate and scarce wood supply.

Foundations were built from layers of rock over a wooden base, while double-stacked walls lined with compressed soil provided insulation. The outer layer of turf, cut into strings, diamonds, or squares, created the signature grassy surface that still evokes Iceland’s early architectural identity.

One of the earliest design innovations was the integration of livestock for heating. Animals were often housed on the ground floor or in adjacent sections, separated by walls from human living areas. The body heat from cows and other livestock rose into the rooms above, keeping living spaces warm during the long, harsh winters and reducing the need for additional heating.

Preserved examples of this practice can be seen at the Skogar Folk Museum in the South Coast of Iceland and the historic Glaumbaer Turf Farm in Skagafjordur, where museum reconstructions and historical interpretations demonstrate how living areas were positioned above animal quarters.

Over time, settlers expanded on this idea by building clusters of interconnected turf houses, sometimes joined by tunnels. These “tunnel farms” maximized insulation, conserved scarce building materials, and protected inhabitants from harsh winds.

Over time, settlers expanded on this idea by building clusters of interconnected turf houses, sometimes joined by tunnels. These “tunnel farms” maximized insulation, conserved scarce building materials, and protected inhabitants from harsh winds.

The layout allowed warmth from people and animals to circulate through multiple rooms while accommodating extended families, farmhands, and livestock efficiently.

Several turf houses survive as key examples of Icelandic vernacular architecture. Large complexes, including Glaumbaer in Skagafjordur, Laufas in Eyjafjordur, and Bustarfell in Vopnafjordur preserve multi-building layouts and traditional construction techniques.

Smaller preserved sites, like Skaftafell and the turf farm at Arbaer Open Air Museum in Reykjavik, provide detailed insight into construction methods, spatial organization, and the adaptation to harsh climatic conditions.

Turf houses are more than historical relics. They highlight a culture of resourcefulness and innovation that continues to influence Icelandic architecture today, linking past ingenuity to the nation’s modern design ethos.

The Industrial Shift: Stone & The Father of Reykjavik

By the mid-18th century, Iceland began transitioning from turf to stone as a primary building material. The Danish government encouraged industrial development, prompting the rise of stone houses across the country, primarily for official and public purposes. At the same time, Reykjavik began to take shape as a trading post and the hub of the nation’s first industrial activity.

By the mid-18th century, Iceland began transitioning from turf to stone as a primary building material. The Danish government encouraged industrial development, prompting the rise of stone houses across the country, primarily for official and public purposes. At the same time, Reykjavik began to take shape as a trading post and the hub of the nation’s first industrial activity.

A key figure in this era was Skúli Magnússon, often called the Father of Reykjavik. As Iceland’s federal sheriff and a leading founder of Innréttingar, a national movement promoting industry and enlightenment, he helped usher in a new phase of construction.

Skúli’s Videyjarstofa on Videy Island, a grand stone residence and administrative center, became a model for subsequent buildings. Between 1750 and 1790, a string of stone structures followed, including Bessastadastofa in Gardabaer and Landakirkja Church in the Westman Islands.

Brick was briefly experimented with in the 19th century, but it proved unsuitable for Iceland’s cold, wet climate. Most early brick structures either burned down or were demolished, leading builders to continue favoring durable local stone.

Surviving examples, like Videyjarstofa and Bessastadastofa, offer insight into the materials, techniques, and social ambitions of this early industrial era in Icelandic architecture.

The Colorful Age: Corrugated Iron & Timber

The 1860s brought a transformative upgrade to Icelandic housing: corrugated iron, or bárujárn, imported by British merchants in exchange for wool. While considered plain or industrial elsewhere, iron‑clad homes in Reykjavik proved ideal for the local weather for their durability against wind, rain, and cold.

The 1860s brought a transformative upgrade to Icelandic housing: corrugated iron, or bárujárn, imported by British merchants in exchange for wool. While considered plain or industrial elsewhere, iron‑clad homes in Reykjavik proved ideal for the local weather for their durability against wind, rain, and cold.

Vertical panels provided superior protection and longevity, while brightly painted surfaces both prevented rust and created a vibrant, uniquely Icelandic aesthetic. This blend of function and color defined the look of Icelandic towns.

The adoption of corrugated iron accelerated after the 1915 Reykjavik fire, when authorities mandated fire-resistant building materials. Homes, official buildings, and churches across Reykjavik and Akureyri were clad in iron, with some featuring pressed plates imported from the U.S. to mimic traditional tiles.

In downtown Reykjavik, around Tjornin Pond and in Akureyri’s old town, these colorful, historic buildings still stand.

Corrugated iron became more than a practical solution. It symbolized Icelanders’ ingenuity. By combining resilience, low maintenance, and visual charm, these buildings created a distinctive urban character that remains iconic today.

The Pillars of Icelandic Architecture

Before Iceland developed its own architectural identity, the nation leaned heavily on imported styles and foreign architects. Builders and designers picked and mixed influences freely, using a Gothic style for a church here and a Neoclassical approach for a bank there. This eclectic approach, called Historicism, lasted until the 1930s, when Functionalism and the “cement age” (Steinsteypuöldin) began to reshape Icelandic towns and cities.

Before Iceland developed its own architectural identity, the nation leaned heavily on imported styles and foreign architects. Builders and designers picked and mixed influences freely, using a Gothic style for a church here and a Neoclassical approach for a bank there. This eclectic approach, called Historicism, lasted until the 1930s, when Functionalism and the “cement age” (Steinsteypuöldin) began to reshape Icelandic towns and cities.

Timber houses, sometimes coated in corrugated iron, followed Nordic patterns, while stone structures were often designed by Danish architects. Although Iceland had yet to claim its own style, these early efforts laid the groundwork for the first native architects to leave a lasting imprint on the nation’s urban and rural landscapes.

The following figures are widely regarded as the pillars of 20th-century Icelandic architecture.

Guðjón Samúelsson | The Celebrated Father

When discussing Icelandic architecture, Guðjón Samúelsson (1887–1950) stands apart as its most influential figure. Serving as Iceland’s official state architect for three decades, he shaped much of the country’s architectural identity during a period of rapid social and urban change.

When discussing Icelandic architecture, Guðjón Samúelsson (1887–1950) stands apart as its most influential figure. Serving as Iceland’s official state architect for three decades, he shaped much of the country’s architectural identity during a period of rapid social and urban change.

After studying housing design in Copenhagen, Guðjón returned to Iceland in 1915, the same year a devastating fire destroyed large parts of Reykjavik’s city center. The disaster exposed the vulnerability of imported Norwegian timber houses and accelerated a shift toward concrete as the preferred building material. Guðjón soon found himself designing many of the capital’s most important new structures.

One of his early landmark projects, the Nathan & Olsen House at Austurstraeti 16, later known as Reykjavikurapotek, signaled a turning point in Reykjavik’s architectural character. Inspired by Scandinavian modernism, the building marked the city’s transition toward a more monumental and durable urban form.

While Guðjón drew inspiration from international styles, he also sought to give Iceland something it lacked: an architectural language rooted in its own landscape.

His designs frequently referenced Iceland’s basalt formations, glaciers, and volcanic terrain, influences most famously expressed in Hallgrimskirkja Church and the National Theatre of Iceland.

These natural references extended beyond form to material, with buildings incorporating local stone such as obsidian, quartz, and Iceland spar.

Guðjón’s influence extended beyond individual buildings. As a member of Reykjavik’s first City Planning Committee, he played a decisive role in shaping the capital’s layout and long-term development. Though not all of his ambitious ideas were realized, his vision defined Icelandic architecture for generations.

Few figures have left a comparable imprint on Iceland’s built environment, and it is difficult to find an Icelander who does not recognize Guðjón Samúelsson as the architect who gave the nation its architectural backbone.

Rögnvaldur Ólafsson | The Unsung Father

Before Guðjón Samúelsson, Rögnvaldur Ólafsson (1874–1917) laid the foundation for Icelandic architecture as the country’s first native architect. Returning home after studying abroad, he worked during a formative moment in Iceland’s history, shortly after the nation was granted home rule from Denmark.

Before Guðjón Samúelsson, Rögnvaldur Ólafsson (1874–1917) laid the foundation for Icelandic architecture as the country’s first native architect. Returning home after studying abroad, he worked during a formative moment in Iceland’s history, shortly after the nation was granted home rule from Denmark.

Despite a career that lasted little more than a decade, Rögnvaldur designed approximately 150 buildings before his death at the age of forty-three.

His work ranged from Nordic timber houses to early cement constructions and included roughly twenty-five churches, among them Husavikurkirkja in Husavik, widely regarded as one of the most beautiful churches in Iceland.

Rögnvaldur was a committed practitioner of Historicism, freely blending styles while adapting each design to local conditions. His churches, in particular, moved beyond the simple square forms common at the time, introducing variation and stylistic confidence that helped shape Iceland’s rural architectural character.

Though his name is less recognized today, Rögnvaldur’s influence was foundational. He introduced new materials, broadened architectural ambition, and helped establish a profession that would soon flourish through the work of those who followed.

His other notable works include:

-

Reykjavik Post Office on Austurstraeti Street, now a popular food hall

-

Keflavikurkirkja Church in Keflavik

-

Hafnarfjardarkirkja Church in Hafnarfjordur

Einar Sveinsson | The Face of Reykjavik

Einar combined technical precision with aesthetic sensibility, ensuring concrete structures from the 1930s–40s remain robust and visually appealing.

Einar combined technical precision with aesthetic sensibility, ensuring concrete structures from the 1930s–40s remain robust and visually appealing.

Although not a household name, Einar Sveinsson (1906–1973) shaped Reykjavik more than almost any other architect of the 20th century. His work is embedded throughout the capital, from hospitals and schools to entire residential neighborhoods.

Trained in Germany, Einar became Iceland’s leading advocate of Functionalism, an architectural approach in which a building’s purpose dictates its form. Returning home, he quickly realized that international functionalist ideas could not be applied wholesale to Iceland’s climate. Elements such as flat roofs, common elsewhere in Europe, proved unsuitable and were adapted accordingly.

As an official state architect from 1934 onward, Einar designed durable concrete buildings that balanced restraint with clarity. His structures prioritized longevity and practicality without abandoning aesthetic consideration, a balance that explains why many of his buildings from the 1930s and 1940s remain remarkably well preserved today.

Beyond individual landmarks, Einar influenced the layout of Reykjavik itself, contributing to the planning of entire neighborhoods, including those surrounding Ellidaardalur Valley. His work gave form to the modern capital, shaping how Reykjavik grew and functioned as a city.

Einar’s legacy lies not in iconic monuments, but in the everyday architecture that defines Reykjavik’s character and continues to serve its residents nearly a century later.

Einar Þorsteinn Ásgeirsson | The Genius Geometrist

Einar Þorsteinn Ásgeirsson (1927–2015) was one of Iceland’s most unconventional architectural minds. Rather than focusing on traditional building design, his life’s work centered on geometry, symmetry, and spatial systems that challenged established architectural norms.

Einar Þorsteinn Ásgeirsson (1927–2015) was one of Iceland’s most unconventional architectural minds. Rather than focusing on traditional building design, his life’s work centered on geometry, symmetry, and spatial systems that challenged established architectural norms.

He developed a fivefold symmetry system known as gullinfang, a geometric concept that later became central to the glass facade of Harpa Concert Hall and Conference Centre.

Although artist Ólafur Elíasson is credited as Harpa’s lead designer, it was Einar’s mathematical research that made the structure possible. The façade is often said to reflect Iceland’s basalt columns, but its form originates instead from Einar’s decades-long exploration of three-dimensional geometry.

Einar’s work attracted international recognition. He collaborated with architect Frei Otto and was approached by NASA to help design portable lunar research laboratories. Despite this acclaim, he remained uninterested in fame, preferring physical models and hands-on experimentation over digital tools.

In Iceland, Einar applied his ideas to ecological and forward-thinking housing. He designed geodesic and tensile structures that blended into the landscape, including his own dome-shaped home near Hella. Many of these buildings incorporated turf roofs, not as a nostalgic gesture, but as a practical and sustainable solution with excellent insulating properties.

Ahead of his time in both theory and practice, Einar Þorsteinn Ásgeirsson bridged architecture, mathematics, and environmental design, leaving behind a legacy that continues to influence Icelandic architecture in subtle but profound ways.

Högna Sigurðardóttir | The Radical Modernist

Image Credit: Bakkaflöt 1 in Garðabær from RÚV. No edits made.

Högna Sigurðardóttir (1929–2017) broke new ground as the first woman to design a house in Iceland and remains one of the country’s most uncompromising architectural voices.

She studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, becoming the first Icelander admitted to the prestigious institution. She later established her practice in France but continued to shape Icelandic architecture through a small number of highly influential projects built between the 1960s and 1970s.

Her work is often associated with Modern Brutalism, characterized by raw concrete, strong geometric forms, and an intense integration of structure and interior. She designed buildings as complete environments, incorporating built-in furniture, fireplaces, skylights, and even flower pots into a unified spatial experience.

Her most celebrated Icelandic project, the Bakkaflot 1 in Gardabaer (1965–1968), exemplifies this philosophy. Partially embedded into a grass-covered mound, the structure dissolves into the landscape, echoing traditional Icelandic turf houses while embracing modern concrete construction.

In 2000, Bakkaflot was recognized in an international survey as one of the 100 most remarkable buildings of the twentieth century in Northern and Central Europe. Högna later received the Honorary Medal for Visual Arts from the Akureyri Art Museum for what was described as a unique lifetime contribution to Icelandic architecture.

Modern and Contemporary Architecture: A Sustainable Revolution

Modern Icelandic architecture is defined by a close relationship with the island’s volcanic landscape. Since the mid-20th century, the Cement Age has gradually given way to a design philosophy rooted in sustainability and Nordic minimalism, where buildings are intended to complement their surroundings rather than compete with them.

Modern Icelandic architecture is defined by a close relationship with the island’s volcanic landscape. Since the mid-20th century, the Cement Age has gradually given way to a design philosophy rooted in sustainability and Nordic minimalism, where buildings are intended to complement their surroundings rather than compete with them.

Today, architectural priorities focus on energy efficiency and durable, low-maintenance materials such as zinc, glass, and timber. A defining advantage is the widespread integration of geothermal heating directly into building design.

With approximately 90 percent of Icelandic homes heated by geothermal energy, architects are able to experiment with expansive glazing, open-plan interiors, and light-filled spaces that would be difficult to sustain in many other cold climates.

Contemporary architecture in Iceland continues to push boundaries while remaining environmentally grounded. Firms such as Basalt Architects, known for projects like the Blue Lagoon, have helped establish a modern architectural language that blends seamlessly into lava fields and geothermal terrain.

At the conceptual forefront, s.ap arkitektar gained international recognition for their Lavaforming project, which explored the potential of controlled lava flows as a construction material and represented Iceland at the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale.

Rather than imposing form on the land, modern Icelandic architecture evolves through adaptation and restraint. It remains an ongoing dialogue between human innovation and a landscape shaped by fire, ice, and constant geological change.

Top 5 Iconic Structures & Landmarks to Visit in Iceland

Whether you are exploring the capital or the remote fjords, these landmarks are the crown jewels of Icelandic architecture. Each represents a specific era of the nation’s survival and artistic growth.

Whether you are exploring the capital or the remote fjords, these landmarks are the crown jewels of Icelandic architecture. Each represents a specific era of the nation’s survival and artistic growth.

5. Akureyrarkirkja

Akureyrarkirkja, the iconic church in North Iceland, showcases Guðjón Samúelsson’s signature design style. Its unique bas-reliefs and massive 3,200-pipe organ make it a cultural centerpiece and a highlight of many Akureyri tours.

Akureyrarkirkja, the iconic church in North Iceland, showcases Guðjón Samúelsson’s signature design style. Its unique bas-reliefs and massive 3,200-pipe organ make it a cultural centerpiece and a highlight of many Akureyri tours.

The church is also a featured stop on popular Ring Road excursions, including the 8-Day Guided Tour of the Complete Ring Road of Iceland, which includes must-see activities along the way. Independent travelers can explore Akureyrarkirkja on a self-drive tour of the complete Ring Road of Iceland, enjoying the freedom to stop at other landmarks and local attractions along the journey.

4. Glaumbaer Turf Farm

Glaumbaer Turf Farm is one of Iceland’s most captivating and best-preserved examples of 18th- and 19th-century turf houses. The earthen walls and lush turf roofs showcase the clever ways early Icelanders stayed warm against the fierce North Atlantic winds.

Glaumbaer Turf Farm is one of Iceland’s most captivating and best-preserved examples of 18th- and 19th-century turf houses. The earthen walls and lush turf roofs showcase the clever ways early Icelanders stayed warm against the fierce North Atlantic winds.

This remarkable site ranks among the top things to see from Akureyri to Snaefellsnes, offering visitors a vivid glimpse into Iceland’s rural past.

Travelers can explore Glaumbaer on a Ring Road and Snaefellsnes Peninsula tour, with nearby highlights including the sweeping Skagafjordur Valley, local heritage museums, and charming farmsteads. Together, these attractions make the farm a must-see stop on any Iceland itinerary.

3. The Retreat at Blue Lagoon

The Retreat at Blue Lagoon is carved directly into an 800-year-old lava field, seamlessly blending luxury with Iceland’s geothermal landscape. Its minimalist design incorporates the surrounding steam and milky-blue lagoon waters, creating a serene, otherworldly experience. Visitors can stay at The Retreat or see it firsthand by booking Blue Lagoon tours.

The Retreat at Blue Lagoon is carved directly into an 800-year-old lava field, seamlessly blending luxury with Iceland’s geothermal landscape. Its minimalist design incorporates the surrounding steam and milky-blue lagoon waters, creating a serene, otherworldly experience. Visitors can stay at The Retreat or see it firsthand by booking Blue Lagoon tours.

The Retreat has earned top design honors such as the Red Dot Award: Best of the Best (2019), Architecture MasterPrize (2019), and the AHEAD Global Awards Sanctuary (2020) for its innovative integration with nature and luxurious interior design.

The property uses natural materials, a monochromatic palette, and high-quality finishes, including wood coatings by ICA, to harmonize with the lava field, making it a standout example of Icelandic contemporary architecture.

2. Hallgrimskirkja Church

Reykjavik’s skyline is dominated by Hallgrimskirkja, an expressionist masterpiece by Guðjón Samúelsson completed over 41 years. Its soaring wings and dramatic tower are inspired by cooling lava flows and geometric basalt columns, making it one of the most famous landmarks in Iceland.

Visitors can admire this iconic church while sightseeing in Reykjavik, taking in the views from different parts of the city.

Hallgrimskirkja is also a highlight of any walking tour of Reykjavik's historical and cultural sites, where travelers learn about its design, construction, and the natural inspirations behind it. Its blend of monumental architecture and Icelandic landscape motifs makes it an essential stop for anyone exploring the capital.

1. Harpa Concert Hall

Harpa Concert Hall, Reykjavik’s modern architectural icon, was completed in 2011 and designed by Henning Larsen Architects and Batteríið Architects in collaboration with artist Ólafur Elíasson. Its shimmering facade, inspired by Iceland’s basalt columns at Svartifoss Waterfall, features over 700 geometric glass panels that play with light and reflection.

Harpa has earned international acclaim, including the 2013 Mies van der Rohe Award for contemporary architecture, the Civic Trust Award (2012), and recognition as the Best Public Space (2013), making it a standout example of Icelandic modern design. It is a must-visit for anyone exploring top things to do in Reykjavik.

Experience Iceland Through Its Architecture

Icelandic architecture traces a journey from Viking Age turf houses to modern marvels like Harpa Concert Hall and The Retreat at Blue Lagoon. Each building reflects the island’s geology, climate, and culture, showing how human creativity adapts to dramatic landscapes.

Icelandic architecture traces a journey from Viking Age turf houses to modern marvels like Harpa Concert Hall and The Retreat at Blue Lagoon. Each building reflects the island’s geology, climate, and culture, showing how human creativity adapts to dramatic landscapes.

Exploring these structures brings Iceland’s history and innovation to life. From the practical ingenuity of turf-roofed homes to the bold, contemporary designs of Reykjavik, visitors witness how tradition and modernity coexist, creating a unique architectural story shaped by the geology of Iceland.

What is the most famous building in Iceland?

Why are there colorful corrugated iron houses in Iceland?

Who are the most famous architects in Iceland?

Why do Icelandic houses have turf roofs?

What defines modern Icelandic architecture?

Which buildings showcase Iceland’s contemporary design?

How have natural landscapes influenced Icelandic architecture?

Which Icelandic landmark would you love to visit first? Is it the history, the design, or the dramatic landscapes that draw you in? Share your picks and thoughts in the comments below!