Understanding Time in Iceland

What is the current local time in Reykjavík, Iceland? What is the duration of the country’s longest and shortest days? How did Iceland's Viking settlers measure time and is it true that summer sees the island enveloped in undying daylight, while winter plunges it into silent darkness? Read on and discover the magical qualities of time in Iceland.

- Learn more fascinating facts in Folklore in Iceland

- See the differences throughout the year in Iceland's Seasonal Contrasts

Time in Iceland is a strange thing. The summer months are bathed in perpetual sunlight, regardless of whether or not the clock tells you it's nighttime. The winter summons an all-enveloping darkness—a long, long night in which the people here live, work and prosper.

So strange is the passing of time here, that Icelanders still fail to recognise autumn and spring with any tangibility. Life is divided between the warm glow of high summer and the mid winter's darkness in which most of the island nation only sees around four hours of effective daylight.

Those who inhabit the most remote Icelandic fjords, particularly in the west, do not see the sun rise above the surrounding mountains for up to five months during winter.

The longest day of the year occurs during the summer solstice, which falls around June 21. This is the time of the Midnight Sun which provides twenty-four hours of daylight, never setting beyond the ocean's horizon, although sunrise and sunset are measured between 2:55 AM and 0:03 AM.

The shortest day of the year occurs during the winter solstice, which falls around December 21. Then, the sun rises and sets between 11:22 AM and 3:29 PM, although it cannot be seen at all in many parts of Iceland.

In between the extremes of winter and summer lays something of a twilight zone, reminiscent of more common global light patterns, but still elusive, undefinable and ever-changing.

Monthly Daylight Hours in Iceland

| Month | Sun Rise Time | Sun Set Time | Daylight Hours (total) |

| January | 11:21 AM - 10:15 AM | 3:41 PM - 5:08 PM | 4h20m - 6h55m |

| February | 10:12 AM - 8:44 AM | 5:11 PM - 6:39 PM | 6h59m - 9h55m |

| March | 8:40 AM - 6:54 AM | 6:42 PM - 8:12 PM | 10h02m - 13h18m |

| April | 6:50 AM - 5:08 AM | 8:15 PM - 9:44 PM | 13h31m - 16h36m |

| May | 5:04 AM - 3:29 AM | 9:47 PM - 11:23 PM | 16h43m - 19h54m |

| June | 3:26 AM - 3:02 AM | 11:26 PM - 11:59 PM | 20h - 20h57m |

| July | 3:03 AM - 4:27 AM | 11:58 PM - 10:39 PM | 20h55m - 18h12m |

| August | 4:30 AM - 6:03 AM | 10:36 PM - 9:62 PM | 18h06m - 14h49m |

| September | 6:06 AM - 7:30 AM | 8:48 PM - 7:05 PM | 14h32m - 11h35m |

| October | 7:32 AM - 9:03 AM | 7:01 PM - 5:18 PM | 11h29m - 8h15m |

| November | 9:06 AM - 10:39 AM | 5:15 PM - 3:52 PM | 8h09m - 5h13m |

| December | 10:42 AM - 11:22 AM | 3:50 PM - 3:38 PM | 5h08m - 4h16m |

- See Also: 13 Reasons to Visit Iceland

Spending a period of time in Iceland, however, confuses one’s preconceived notions of the natural equilibrium and forces one to acknowledge the strangeness of human consciousness and the transience of existence.

A Little About Time Itself

For eons, humans have used the stars, sun and moon to navigate and plant themselves in between a past and a future, in a moment they can securely call ‘now’. How one should read and define the present moment is still being disputed, though the reality of its existence is something most of us readily take for granted.

This ‘now’ can be written out as whatever time our clocks measure, but in the sense of our own lives, time exists as the realisation that we are here, that we have been here, and that we will, with good luck, continue to be.

Time envelopes our existence as seamlessly as gravity, motion, space and energy. In fact, it is almost impossible to consider any field of human endeavour or thought where, in one shape or another, time does not play an important factor.

- See Also: The Nature of Icelanders

The Old Icelandic Calendar

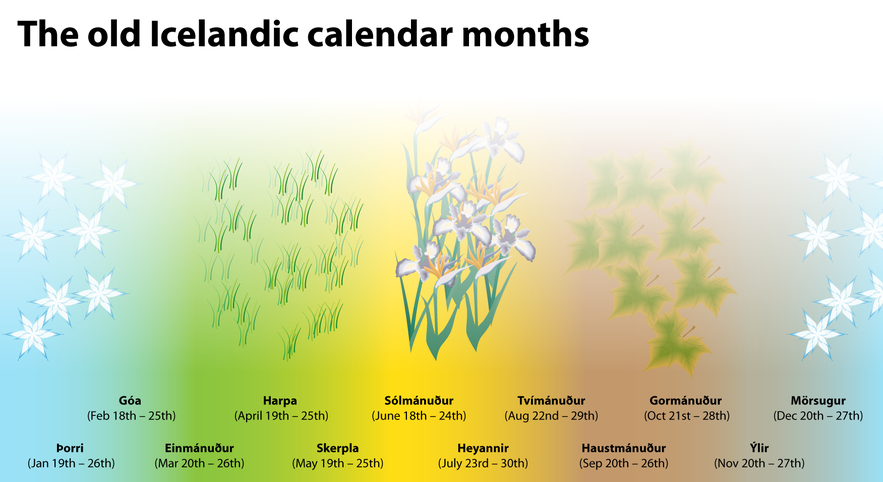

The Old Icelandic Calendar was based around the movements of the sky, the winter Equinox acting as the population’s collective marker for the rebirth of summer. This isn’t surprising considering the harsh, short days that Iceland suffers.

If foreign guests ask Icelanders as to the whereabouts of spring or autumn, they will likely tell you that Iceland doesn’t recognise these transitional seasons; it is perpetually summer or winter.

This might have something to do with how the fact that the Old Norse calendar was split into two seasons of six, thirty day months (lunar phases).

The months were as follows.

- Harpa, Skerpla, Sólmánuðr (May-July)

- Heyannir, Tvímánuðr and Haustmánuðr (August-October)

- Gormánuðr, Ýlir, Mörsungr (November-January)

- Þorri, Góa and Einmánuðr (February-April)

The days of the week were known as the following:

- Sunnudagr (Sunday, “Sun’s Day”)

- Mánadagr (Monday, “Moon’s Day”)

- Týsdagr (Tuesday, “Tyr’s Day”)

- Óðinsdagr (Wednesday, “Odin’s Day”)

- Þórsdagr (Thursday, “Thor’s Day”)

- Frjádagr (Friday, “Freya’s Day”)

- Laugardagr (Saturday, “Bath Day”)

With thirty days in each month, ancient Icelanders saw three hundred and sixty days in the year. To compensate and synchronise with the solar year, a further week was added at the end of each seven year period. This was called “sumarauki”, literally “the summer addition.” In this sense, the Icelandic calendar used ‘leap weeks’, rather than days or years.

The ancient Landnámabók (“Book of Settlements”) traces the invention of this practice to the ingenuity of a single man: ‘Hallsteinn had Ósk, daughter of Þorstein the red. Their son was Þorsteinn surtr, who invented the summer addition’.

Though it is not known for certain, it is widely considered that the Viking new year began on the first day of the first summer month. This is because the settlers used to measure their age by the number of winters they had lived through.

This method of calculation is still used today by Icelandic farmers when referring to their livestock; and the first day of summer is to this day a public celebration in Iceland, falling on the first Thursday after April 18.

Reading the Stars | Timekeeping in the Viking Age

The Norsemen were adept at reading the night sky. Born and bred sailors, an intimate knowledge of the stars was simply fundamental to their survival; therefore, this ancient race maintained a more familial relationship to the celestial bodies than many of us do today.

This relationship was intertwined with the spiritual beliefs of the age; as attested to in Snorri Sturluson's Poetic Edda, in which Máni and Sól are the names given to the human personifications of the moon and the sun.

- See Also: Icelandic Literature for Beginners

The constellation, Þjazi’s Eyes (the Gemini stars Pollux and Castor), appeared as two equally bright ‘eyes’ in the night sky, reaching their highest peak in January. Thus, to the Norse, Þjazi's Eyes were considered a direct link to the Goddess of winter, Skadi.

Still, it must be noted that the Norsemen’s relationship to and comprehension of the stars is far less documented than that of the Greeks, the Chinese or the Babylonians.

- See Also: Elves, Viking and Norse Gods in Iceland

The Sunstone (Sólarsteinn)

There were also tools used by the early settlers to help their timekeeping efforts. A Sunstone (“sólarsteinn”) is a crystalline mineral written about in the sagas as a device used for locating the sun on an overcast day.

According to the Medieval Icelandic source, Rauðúlfs þáttr, the sunstone worked by holding the sheet of mineral toward the sky and reading how the light transmitted through it. As written in Rauðúlfs þáttr;

“The weather was thick and snowy as Sigurður had predicted. Then the king summoned Sigurður and Dagur (Rauðúlfur's sons) to him. The king made people look out and they could nowhere see a clear sky. Then he asked Sigurður to tell where the sun was at that time. He gave a clear assertion. Then the king made them fetch the solar stone and held it up and saw where light radiated from the stone and thus directly verified Sigurður's prediction.”

Despite its attributes being documented in no other source, this representation is considered accurate given the early settler’s ability to understand and predict their seasonal changes.

Today, it is widely believed that the sunstone was Icelandic Spar, a transparent type of calcite. An Icelandic sunstone was also recovered from the 1592 ship wreck, the Alderney, indicating the sunstone was likely used for ocean navigation, even after the invention of the magnetic compass.

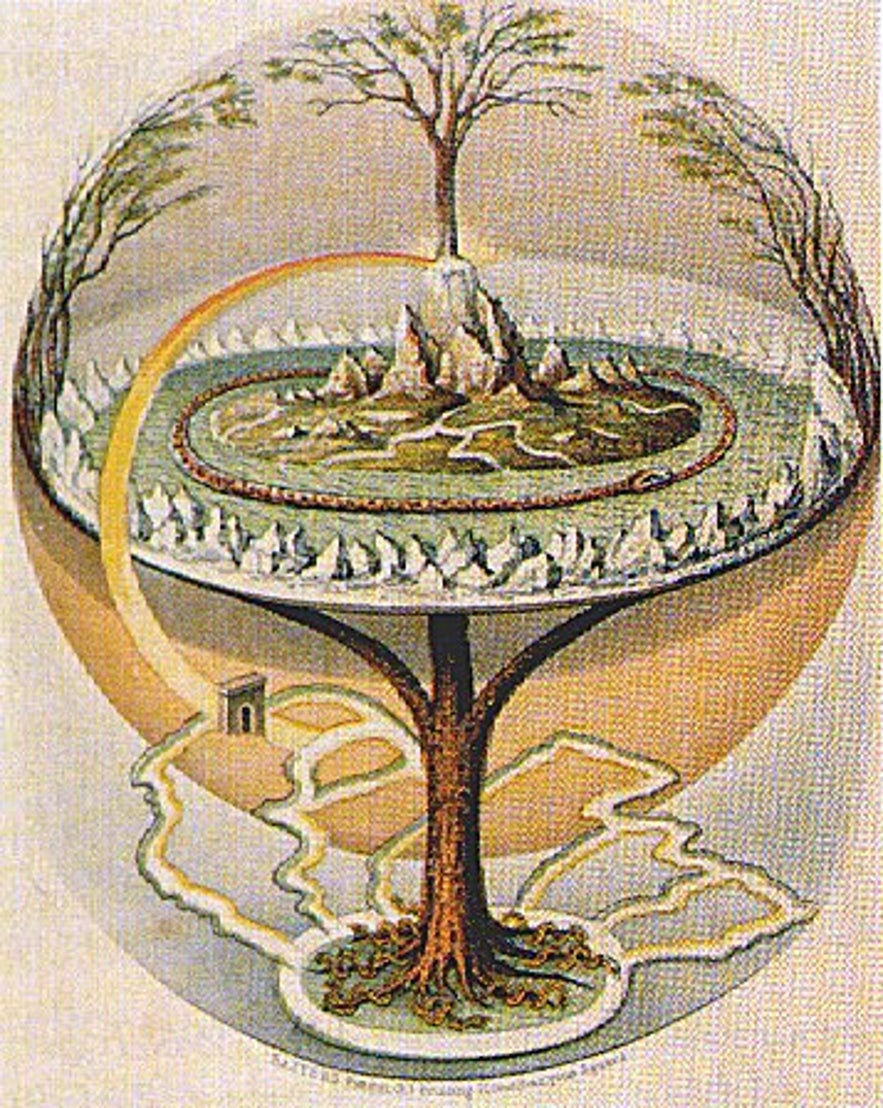

The Landscape Cosmogram Theory

One man who understood the links between time, the stars and the early settlers better than anybody was the Reykjavik-born writer and scholar, Einar Pálsson, recipient of The Knight’s Cross of the Order of the Falcon for his contribution and research into Old Icelandic literature.

In 1969, Einar first put forward his theories on the socio-mythology of the early settlement period, laying down his considerations in a series of eleven books. Out of these, much has been written of the Landscape Cosmogram Theory, a view of explaining the cosmological significance of the geographical locations the early settlers chose to colonise.

- See Also: History and Culture in Iceland

Einar’s research begins with a study of the mythological impact of the Old Icelandic sagas, particularly focusing on how the literature reflects the ritual landscape of the time. According to this theory, a Saga’s characters were seen to personify human concepts; Kári of Njál's Saga represented time and air; Njáll represented creation and water and Skarphéðinn represented death, justice and fire, to name only three characters.

The theory stretches deeper; given the spiritual foundation of life and society in early Iceland, Einar examined the physical measurements and layouts of the colonies established during the Age of Settlements. Considering that life on earth was, to the settlers, a clear reflection of the heaven’s above, it was logical to consider the circular shape such townships took.

A circle was the most natural geometry; symbolic of the zodiac and the horizon line. The spokes of the circle were aligned to cardinal directions and solstice lines, with natural landmarks such as hills and mountains acting as points along these spokes to fix the cosmogram to the surrounding landscape.

Einar is quick to point out the similarities worldwide; the Ceques and Huaca systems utilised by the Incans, for example, perfectly demonstrated this same mirroring between human civilization and the cosmos.

So too does Stonehenge in England, the centre point of a circle whose spokes point directly to other spiritual centres surrounding it. In point of fact, the Landscape Cosmogram Theory can be accurately applied to positions across Europe, North Africa, South America and the Middle East.

The Christianisation of Iceland

The use of the Old Norse Calendar saw its final days upon the Christianisation of Iceland, beginning around 1000 AD. In Icelandic, this is known as kristnitaka, quite literally “the taking of Christianity.” This spiritual adoption did much to change the Icelanders’ traditional approach to time as a concept given its deep connection to religion and nature.

- See Also: Folklore in Iceland

Despite the conquest’s eventual success, however, Icelanders did not take the ecclesiastical takeover of their homeland lightly, with these newfound beliefs and systems taking centuries to settle into the people’s psyche.

Almost all early settlers to Iceland were Pagan, worshipping the Norse Gods, Æsir and the Vanir—two pantheons which enveloped God’s whose dominion hailed over fertility, prophecy, wisdom, nature, sorcery, war and conquest.

This joining of celestial pantheons enforced the core belief that the Norse Pagan religion reflected the character of the landscape, the natural elements and the human psyche.

Christianity then would have seemed like something of a foreign invader, a point made clear in the story of Þorvaldur Konráðsson, who was first to attempt to convert the nation over to monotheism. Þorvaldur was forced to flee his homeland after being met with ridicule and contempt, eventually culminating in the death of two men at his own hand.

It wasn’t until the ascension of Ólafur Tryggvason to the Norwegian throne that pressure to Christianise Iceland began to grow. Determined to unite his empire under a single banner, Ólafur sent a number of missionaries to Iceland, including Stefnir Þorgilsson, who destroyed so many heathen sanctuaries that he was declared an outlaw.

After subsequent failures, King Ólafur felt the need to intensify his efforts. He began taking heavier action against the Icelandic people, including cutting off their access to Norwegian ports, kidnapping Icelanders in Norway and even refusing to continue a trade relationship.

The proposition seemed suddenly too daunting to withstand; the Icelanders were solely reliant on healthy diplomatic ties to Norway, and moreover, the king had threatened to execute the family members of Icelandic chieftains in his custody. A national divide was soon wedged across the people of Iceland, and civil war seemed imminent.

Eventually, the law speaker Þorgeir Þorkelsson was trusted to decide whether or not the country would adopt the tenets of Christianity. Þorgeir was considered a well-learned and reasonable man, and thus both sides of this early holy war trusted his judgement.

After a day and a night of contemplation, Þorgeir came to a conclusion that would change the very fabric of Icelandic culture: The nation would become Christian, while the worship and belief in Norse mythology would be permitted in private (though later banned once the church had firmly established itself).

Iceland’s transition to Christianity was remarkable for its peacefulness, quite in contrast to Norway’s own conversion. Þorgeir himself lead the charge, throwing his pagan idols into the Waterfall of the Gods, Goðafoss and number of changes were quickly implemented; the consumption of horse meat was banned, all citizens were to be baptised and the Icelandic calendar was gradually discontinued and replaced by its Latin counterpart.

The Arctic Henge

Modern-day Icelanders are just as enamoured with the Norse mythological interpretations of the universe as their ancestors. This was made poignantly clear decades ago with the 1972 founding of the pantheistic Ásatrúarfélagið (“Ásatrú Fellowship”).

As Neo-Pagan worshippers, Ásatrúarfélagið focuses its attention on spreading and maintaining the belief in the Norse Gods. In 1992, the religion’s second high-priest, Jörmundur Ingi Hansen, described its practices as follows:

“Ásatrú or heathenry is basically only to realise this dichotomy and to decide to side with the Æsir. The best way to do that, in my opinion, is to be self-consistent, live in harmony with nature, associate with it with respect and to submit to the public order... The gods shape the dwelling places of people, the earth and the solar system out of the material that already exists. To that extent, we can look at the forces of nature as the gods themselves and to a large extent that is what people did in antiquity.”

Amidst many culturally important sites to the Ásatrú Fellowship is the Arctic Henge. Like its ancient, English predecessor of Stone Henge, the Arctic Henge acts as a sun dial, catching the light’s rays to form significant and accurate shadow patterns that relate directly to the movement of the sky.

The site is found in the northeast corner of Iceland, roughly 130km from Húsavík in the remote village of Raufarhöfn.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir. No edits made.

The monument has two main towers that perfectly frame the Midnight Sun during the June Solstice, as well as four arches that symbolise the seasons.

The structure was conceived of by the late Erlingur B Thoroddsen who in 1996 set about creating his unique vision, drawing inspiration from such far-out sources as E.T and the Rolling Stones—which is, arguably, one of the reasons why BBC Travel labelled it “Iceland’s Psychedelic Stonehenge”.

Overall, the Arctic Henge is made of 72 stones, with each individual stone representing one of the 72 dwarves found in the Poetic Edda.

Icelanders and The Present Moment

Physically standing in Iceland offers a perspective on the surrounding world quite unlike that which one can elsewhere expect to experience. Here, an individual stands dwarfed and surrounded by the timeless majesty of the wilderness, taken aback and undistracted from the fleeting anxieties of the human mind and the modern century. In such moments, this space, quite literally, is reflected in the awareness of oneself.

The Icelandic nature, embodied in the old Norse mythology, has an incredible ability to bring people out of themselves, confronting them with the simplest reality of all; that regardlessness of what the clock face reads—the intimate knowledge of being here and now.

- See Also: Yoga in Iceland

Even for those who have an aversion to overt spirituality will feel their personal changes coinciding with the passing seasons. In the summer, Icelanders are perhaps the keenest people on the planet to make the very most of the sunshine. Time, it seems, bends, creating space for open growth, human contact and blissful awareness.

The winters see Icelanders inside of their houses, their minds quieter, a little more isolated, a touch more reflective, their temperament often as cold as the winds blowing outside. Just like flowers in a meadow, their energy is defined by the environment in which they find themselves.

How did you find your experience of time in Iceland? Did you travel during the bright summer months or visit during the long dark of winter? Make sure to tell us of your time here in the comments box below!

Otros artículos interesantes

Localizaciones de películas en Islandia

¿Qué películas y series de televisión internacionales han sido filmadas en Islandia? ¿Por qué eligen los productores Islandia para rodar? Consulta esta lista de personajes famosos de Islandia A...Leer másNochevieja en Islandia

¿Cómo es la Nochevieja en Islandia? ¿Cómo es la Nochevieja en Reikiavik? ¿Qué hace que la Nochevieja en Islandia sea tan especial? ¿Dónde están las mejores fiestas de Nochevieja en Reikiavik? Entérate...Leer más

7 cosas del turismo en Islandia que los islandeses ODIAN

El crecimiento del turismo en Islandia tiene su parte buena... y su parte mala. ¿Qué es lo que más odian los islandeses del turismo en su país? ¿Qué distingue a un 'mal turista', y cómo puedes ser u...Leer más

Descarga la mayor plataforma de viajes a Islandia en tu móvil para gestionar tu viaje al completo desde un solo sitio

Escanea este código QR con la cámara de tu móvil y pulsa en el enlace que aparece para añadir la mayor plataforma de viajes a Islandia a tu bolsillo. Indica tu número de teléfono o dirección de correo electrónico para recibir un SMS o correo electrónico con el enlace de descarga.