Top 9 Most Famous Icelanders in History

Which famous Icelander had the biggest impact on culture and history? Read ahead, to learn of the adventurous Icelandic Vikings, incredible writers, and trail-blazing Icelandic men and women who came from this little island, and went on to change the world.

- Read about more famous Icelanders in the History of Iceland

- Find out more about the people of Iceland in the History of Reykjavík

- Discover the strange group that is The Most Infamous Icelanders in History

When you visit Iceland, you will see places where individuals shaped history in the most consequential of ways. From the earliest settler to the world's first gay leader, Icelanders have been vital in shaping human culture in far greater ways than the size of their population would ever suggest they could.

A comprehensive list of the most famous Icelanders in history is a difficult thing to compile. The country has produced a wealth of musicians, scientists, artists, writers, historians, adventurers and political figures, all with their own significant value. No matter the length of the list, someone would always be left out. Ahead, however, are nine people that it would be almost impossible to exclude.

So read on to learn about nine famous Icelanders who made significant history, from settlement to today.

- See also: Top 10 WORST things about Iceland

Ingolfur Arnarson

Photo by MoreToTheShell

Photo by MoreToTheShell

Ingólfur Arnarson is without a doubt the most important historical Icelander. While Iceland had previously been visited, and a few others had resided on it for short periods, he was the first person brave enough to relocate from Norway, and permanently settle here with his family.

Iceland’s history before Ingólfur and Norse settlement is blurry. It is possible that it was visited as far back as the fourth century BC; there is a vague description of a land called ‘Thule’ by Ancient Greek geographer and explorer Pytheas that some suspect to be Iceland.

Furthermore, Roman coins from the beginning of the third century AD have also been discovered, and although they were most likely brought over by later visitors, no one is quite certain of this.

It is known that Scottish and Irish monks made temporary residence on the island in the 9th Century before the Norse came, but it is not known for how long, or when and why they left. Some believe they departed because they noted growing interest in the place by the notorious Vikings, and wanted to get as far from them as possible.

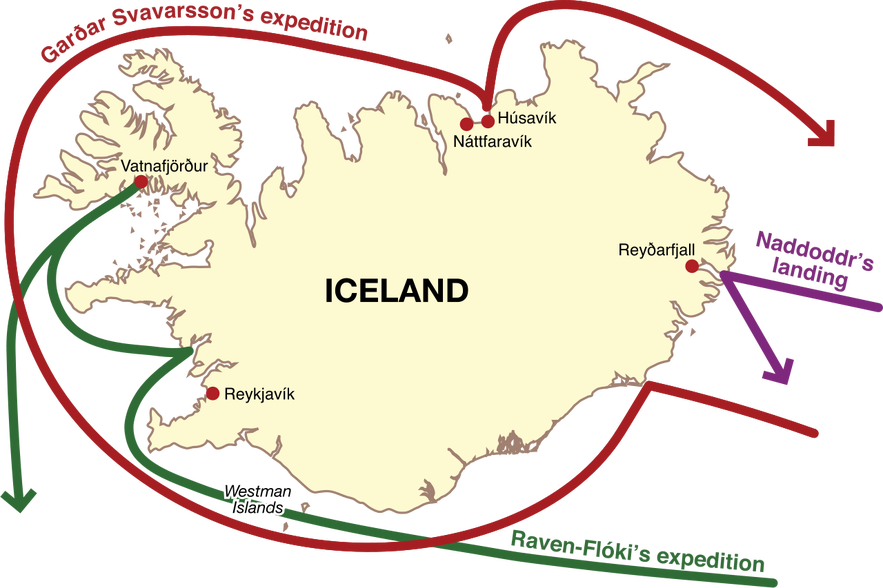

The first Viking known to have seen Iceland was an explorer called Naddoður, who named it ‘Snowland’; the second was a Swede called Garðar Svavarsson, who named it after himself. Neither of these Vikings, however, settled long on the island, so neither make this list.

The first to travel to Iceland intentionally and stay for a prolonged period was Hrafna Floki. He first wintered on Iceland’s shores, then returned to live the last of his days here, in spite of how he complained of how inhospitable it was for the years between. Hrafna Floki can be credited with giving the country its current name but is not considered a true Icelander because of his attitudes to the land.

Ingólfur is thus considered the first proper settler, having lived in Iceland permanently since his arrival in 874. Most of what is known of him comes from the iconic Book of Settlements, called Landnáma in Icelandic, which was written by Ari Þorgilsson. Although comprehensive, detailed, and a vital work in understanding medieval Viking history, the oldest parts are still two hundred years younger than Arnarson, so it is not completely reliable.

What is said, however, is that he settled and named Reykjavík. This began the settlement period of Iceland, which finished when the Commonwealth era began, with the creation of the Althing in 930 AD. Like many who moved to Iceland, Ingólfur did so to escape the consequences of a blood-feud and the violent politics between the jarls of Norway.

- Find A walk with a Viking tour here

Ingólfur is also renowned for his role in the naming of the Westman Islands. While those who initially chose to move to Iceland were all Norse, they brought with them many Irish slaves. These people were called Westmen as, before Iceland’s discovery, Ireland was thought to be the westernmost landmass. Two of these slaves fought against their chains and killed their master, who unfortunately for them was Ingólfur’s brother-in-law.

They fled to a group of islands south of the mainland, but Ingólfur hunted them down and killed them. Ever since, the islands have been named after them.

Ingólfur’s influence on Iceland’s history is indisputable. He and his wife Hallveig can be considered the nation’s father and mother, and the first true Icelanders.

On the green hill Arnarhóll, a statue of Ingólfur Arnason overlooks central Reykjavík. To learn more about Ingólfur Arnason, one could visit the Saga Museum, also in the capital, which has an exhibition dedicated to him. To learn more about the settlement era altogether, there is the excellent Settlement Centre Museum in Borganes.

- Find a Viking horseback tour here

Leif the Lucky

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Thomas Quine. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Thomas Quine. No edits made.

Leif the Lucky, born c. 970 AD, was one of Iceland’s most incredible explorers. The only European of his time whose achievements in discovery match his, is his father, Erik the Red.

Erik and Leif are credited with being the first Europeans to settle Greenland and North America respectively. Erik first came to Iceland because his father was exiled from Norway for murder; he settled with a family here, having Leif, before being exiled himself for the same crime.

First, he was sent to an island off Iceland, but on repeating his offence, was exiled completely for three years. He used this time to sail around Greenland.

Leif joined his father in these travels, learning about ship craft as he did. This only added to his many skills; he had been raised by a learned man whom his father had captured and was already fluent in several languages, knowledgeable about literature, trained in weaponry and skilled at trade. Thus, by the time the family returned to Iceland, and Erik rallied a group of people to settle the new land, Leif was a very well-rounded young man.

- See also: Sail like an Icelandic Viking

His skills did not go unnoticed. He was invited to Norway, and became a hirdman, or Housecarl, for the King Olaf Tryggvasson. He was baptised and brought Christianity to Greenland when he returned. He was restless in this new settlement, however, and like his father, sought to explore the lands rumoured to exist to the west.

He thus led an expedition and came to North America. He was not the first to discover it (there were, of course, millions of people who had been there for millenniums, and other sailors who had claimed to have seen it), but he was the first European to explore and form a settlement on it. On the discovery of many grapes and berries near where his ship landed, he named the new world Vínland, or Wineland.

He returned to Greenland to take over his father’s role upon his death, but the settlement he created was not well-maintained. It is believed that Native Americans killed the few who stayed, and it almost became forgotten in the annals of history.

The main evidence that this American community ever existed is what was written in the Book of Settlements, but as it was not mentioned in wider European literature, it was considered to be a legend for centuries. This was the case until archaeological excavations in Newfoundland proved it to be true in 1960.

That does not mean, however, it was completely forgotten in this time. It is rumoured that Christopher Columbus knew that he would reach the Americas, rather than India, on his voyage to the New World; he claimed to have visited Iceland in 1477, where he may have heard legends of Leif’s travels to lands to the west.

The travels of Leif, like those of his father, were vital in many areas; he increased understanding of the geography of the world, crossed oceans when much of the world believed they had no end, and inspired future adventurers. His place on this list, therefore, is indisputable.

To learn more about Leif, you could visit several places around Iceland. In Eiríksstaðir, there is a replica of the Viking longhouse in which Erik lived and Leif was born. Here, you can immerse yourself in Viking-age Iceland, with staff dressed in traditional regalia, ready to inform you all about these national heroes and how they lived. The Viking World Museum, in Njarðvík near Keflavík, also has a replica of Leif’s ship on display.

Outside of Hallgrímskírkja church in Reykjavík, there is a statue of this legendary explorer, which is probably the most photographed statue in the country.

- See also: Regína's trip to Eiríksstaðir

- Find The Viking Adventure Tour here

SnorriSturluson

Painting by Christian Krohg, 1852 - 1925

Painting by Christian Krohg, 1852 - 1925

Thus far, the famous Icelanders listed have been men best remembered for their actions; Snorri Sturluson, however, is best remembered for his words. Both he and the aforementioned Ari Þorgillson were medieval writers who produced a huge wealth of information about history at the time, still vital to historians to this day, and both dramatically advanced the culture of Iceland.

The only reason Snorri sneaks ahead or Ari on this list is because his texts have wider implications within European history, and because of his influences outside of his writings.

Snorri is best known for two books, although he wrote much more. The first of these is the Bible of Old Norse mythology, Edda, now regularly referred to as Snorri’s Edda. Snorri was the first person to compile the stories and tales about how the Vikings believed the world and gods were created into one volume. Now, it is considered a masterpiece and has inspired writers and artists from Tolkien to Nicolai Abildgaard.

The other work was Heimskringla, an account of Scandinavian kings and their lineages. While this may not seem to be a thrilling read, in fact, it fills a huge gap in history; most knowledge about the medieval era in Europe has disappeared, and this is the sole source for much of what we have since learnt about it.

Snorri’s was raised by a relative of the Norwegian king in Iceland, which was agreed upon by his father as a way for him to receive compensation after he was attacked in a dispute at the Althing. Because of his caregiver's background, Snorri received an exemplary education. This upbringing made him quite the eligible bachelor, so he was able to marry not only into land and wealth but into a chieftainship.

While his infidelities meant his marriage did not last when he relocated to Reykholt, he was well-known and loved across the country for his poetry. Because of the fame this gave him, he was chosen for the most important role in Iceland at the time, becoming Law Speaker of the Althing in 1215. He left the post on the invitation to join the Norwegian king’s court, where he wrote poetry and the history of the royal lineage in exchange for a showering of gifts.

He returned to Iceland and resumed his role as lawspeaker from 1222 to 1232, now believing that Iceland should join the Norwegian kingdom. This sewed a great amount of discord between him and many chiefs across the commonwealth. As Norway tried to force its influence more and more, tensions continued to rise until civil war broke out.

When Snorri returned to Norway, however, he found the King no longer to be a trusted friend, and was not permitted to leave. He did so regardless, returning to Iceland during one of its most tumultuous times.

Though both sides of the war bore umbrage with his role in the division, when he was assassinated in his home in 1241, it was widely considered to be an affront to his name and titles. Therefore, in both nations, he was remembered fondly, and could, posthumously, rebuild his reputation as an incredible writer and historian.

The Saga Museum in Reykjavík has an exhibition on Snorri’s life as a poet and a politician. Snorrastofa Museum in Reykholt is dedicated to his works and is situated in the town where he did the majority of his writings. The National Museum of Iceland has medieval manuscripts including Snorri’s Edda on display.

- See also: The top 6 museums in Reykjavík

- See also: Snorri Sturluson - the most influential Icelander ever

Briet Bjarnhedinsdottir

The next person to enter this list was born over six hundred years after Snorri. That is not to say that Iceland did not have its share of significant people in that time, but under Norwegian and subsequently Danish rule, Iceland was incredibly poor and undeveloped. Opportunities to break out of fishing and farming communities to challenge the values of the world were practically non-existent.

Photo from Store Norske Leksikon

Photo from Store Norske Leksikon

Bríet Bjarnhéðinsdóttir, however, born in a developing Reykjavík in 1856, managed to make herself known. In her lifetime, she changed the way that Iceland viewed women forever, to the extent that Iceland now leads the world when it comes to women’s rights. While in the UK, there is Emmeline Pankhurst, and in the US, figures such as Susan Anthony and Sojourner Truth, Iceland has the legendary Bríet.

Before she was ever formally introduced to the suffrage movement, Bríet was active in promoting women’s interests. She founded the Women’s Society in 1894, and owned a women’s magazine that was well-loved around the country. Initially, her interpretation of females roles in the public sphere was to promote and protect children, the disadvantaged, and the poor. As she began to travel Europe in the early 1900s, however, she soon learnt of the wider international movement of enfranchisement.

Because of her magazine, she was invited to the International Women’s Suffrage Conference, held in Copenhagen in 1906. There, she was encouraged to bring the movement to Iceland, and she brought it with force.

Her magazine became a political tool to motivate women to demand their rights to vote. She formed the Icelandic Women’s Rights Association, or Kvenréttindafélag Íslands, in 1907, which still exists today.

Women were permitted to participate in municipal elections, so she formed a women’s party, the success of which shocked the Reykjavík establishment. While this had significant backlash, with concerns that further enfranchisement would lead to women dominating men, it started a movement that was all but impossible to reverse.

She presided over the Women’s Rights Association twice, when it was first established, then again from 1912 to 1927. During this time, Iceland’s oppressive democratic system, which excluded women and men without property, crumbled. In 1915, women over 40 who were not servants were granted the right to vote, and in 1920, the franchise was made universal.

While Bríet did not herself get elected to the Althing, she lived to see women break through this first glass ceiling. Ingibjörg Bjarnason became the first female elected to the national parliament in 1922.

Bríet played a major role in propelling Iceland from a patriarchal society into a bastion of women’s rights, literacy, universal education, and social justice. Iceland has now been listed as the world’s most gender-equal country for eight years running, according to the World Economic Forum’s survey on gender equality, and comes near the top of multiple other lists, such as the most educated and the happiest nations.

There is a growing movement in Iceland to include more ‘herstory’ within the city museums and to raise a statue of Bríet, although these demands are only just gaining traction. If you wish to learn more about Bríet and her wider movement, check with museums before attending to see if any temporary exhibitions are on display. Reykjavík City Museum and the Photography Museum have, in the past, hosted features about the 1975 Women’s Day Off, and the suffrage movement.

- See also: Gender equality in Iceland

Sigridur Tomasdottir

Iceland may have Bríet to thank for becoming a progressive place for women’s rights, but it has Sigríður Tómasdóttir to thank for the deep-seated cultural appreciation for nature. Considered to be Iceland’s first environmental campaigner, she fought for the preservation of one of the country’s most beautiful features and in doing so, inspired changes in laws that would keep so much of her land protected.

Partly due to her influence, Iceland has become a bastion of environmentalism, with huge swathes of untouched nature and energy that comes entirely from renewable sources.

Sigríður was born to in 1874, daughter of a man called Tómas who owned the farmland surrounding Gullfoss waterfall, now one of Iceland’s most popular tourist destinations. She and her sisters laid the first path down to the falls, and would take visitors to come and see it; even in the 19th Century, it drew people from around the world. Tómas would refer to the waterfall as his friend, and his sentiment was felt throughout his family.

The interest in the waterfall from some foreign visitors, however, did not stem from its beauty; it stemmed from its potential for profit. British businessmen believed they could use the waterfall to harness huge amounts of energy, and sought permission to dam it.

Tómas refused this offer completely, unwilling to sell no matter the cost. The businessmen, however, were savvier with the law and found a loophole that would allow them to follow their plans regardless. Tómas and his family were distraught; Sigríður, however, was livid.

She had received no formal education; she had lived her whole life on the farm; and this farm was about a hundred kilometres from Reykjavík, the only place where anyone could halt the plans. She let none of this stop her. Over and over again, she walked to and from the capital to meet with a lawyer, in a relentless attempt to protect Gullfoss.

Her efforts seemed futile against the capitalist machine that was moving the plans forward, but she refused to accept defeat. She drew attention by threatening to throw herself from the falls should they be sacrificed for the profits of a few.

Thankfully, she never had to see her threat through. While her work was not what directly saved the falls - it was more to do with a lack of funds on the part of the businessmen - it pushed legislation through the Althing that declared no state-owned waterfall could be sold to foreign nationals. Her work later ensured the official protection of Gullfoss for future generations to come.

Her resilience in valuing nature over profit made her Iceland’s first environmental campaigner. Now, a nation follows her ideology. Icelanders are incredibly proud of their environment and incredibly protective over it. Tourism to the country is as eco-friendly as can be, and the only time when residents tend to have a problem with visitors is when they do not show Iceland’s environment the respect it deserves.

A relief statue of Sigríður stands at Gullfoss, with information signs detailing who she was and what she did. After marvelling at the beauty of the waterfall, it is great to be able to see and appreciate the unlikely figure who helped to save it. Gullfoss is a stop most visitors will get to; it is one of the three stops of the famous Golden Circle.

- See also: What is the Golden Circle?

Halldor Laxness

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Friedrich Magnussen. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Friedrich Magnussen. No edits made.

Any list of famous Icelanders would be remiss if it excluded the nation’s only Nobel Prize winner. Halldór Laxness, born in 1902, followed Iceland’s long history of mastering the written word and used it to tell fascinating stories that speak of the hardships and conflicts of not only Icelanders but of the human soul. Without a doubt, Laxness was one of the greatest writers of the 20th Century.

His works were extensive. He wrote essays, poetry, theatre pieces and nonfiction texts. He is best known, however, for his novels. Within them, he perfectly captured the societal tensions of the 20th Century, caused by industrialisation, urbanisation, migration and the decreasing role of centuries old traditions. It was for these creations that he won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

As an interesting side note, although Laxness is Iceland’s only Nobel Laureate, because of the country’s tiny population, it has more Nobel Prize winners than any other nation per capita.

Laxness's novels also paint a vivid picture of Iceland's nature. Christianity at the Glacier, also called Under the Glacier, for example, is set in the shadow of Snæfellsjökull glacier, and introduces readers to the nature of Snæfellsnes Peninsula and the curious residents who live on it.

Perhaps his most esteemed work, however, was Independent People, published in two parts in 1934 and 1935. This novel covers the years up to, during, and after the First World War in Iceland, a period through which the country went from a rural, disconnected land, unchanged for centuries, to a modern nation with electricity and machinery.

The divides created by this quick and dramatic change are illustrated beautifully in this novel, written from the perspective of a croft farmer, just free from debt bondage, who will stop at nothing to achieve his independence.

This protagonist, Bjartur, is determined to the point of callous, but a fantastic representation of Icelanders of old. His struggles are also incredibly relatable, and the themes of independence, community, capitalism and cooperation resonate to this day.

Laxness died in 1998, and in his lifetime, underwent many personal changes that reflected the world around him. He went from a devout Catholic to an ardent critic of Christianity; he changed from a supporter of capitalism to Soviet communism, then to a more gentle socialism, before dropping all doctrines but a loose interpretation of Taoism. He was also caught in a conflict between traditional rural living and the appeal of a modern, convenient life.

Laxness’ old house has been turned into a museum in the valley of Mossfellbær, just outside of Reykjavík. It includes a multimedia presentation telling of his life and works. For those visiting Þingvellir National Park, it is en route and well worth a visit. Laxness’ most famous works are available in most bookshops and souvenir stores.

VigdisFinnbogadottir

The modernisation of Iceland, as mentioned before, brought about great societal change for women. While female suffrage had been achieved decades earlier, however, women were still hugely underrepresented in the public sphere by the 1970s.

It was never, and still is not, in the nature of Icelandic women to wait patiently for justice, however. In the 1975 UN Year of Women, over 90 percent left work, be it paid or domestic, to demand better conditions in the streets of the capital. Following these dramatic protests, they prepared to shatter one of the world’s tallest glass ceilings. Finally, in 1980, a female-led movement pushed Iceland to be the first nation ever to directly and democratically elect a woman as Head of State.

Vigdís Finnbogadóttir was the first woman to be president in Europe and Iceland (there had been others across the world, but none democratically elected). It should be noted that other women had been elected Prime Minister, but that made them the heads of their governments, not their states. Therefore, Vigdís was the first to win a national vote, rather than a vote to lead a party and a subsequent vote to win a constituency.

She was not what you would expect of a female leader in 1980. While figures like Margaret Thatcher, first elected in 1979, used their role as a wife and mother to sell themselves to conservatives who believed that women should stay traditional gender roles, Vigdís was a single mother and divorcee, and unashamed of it. The fact that any woman won the presidency was dramatic; the fact that it was someone whose lifestyle was so contrary to what was customary shocked the world.

She was also not just elected in the furore of the Year of Women. She was soundly reelected three times, serving in office for 16 years. She was popular throughout her terms and is still popular today.

Although the role of president in Iceland is largely ceremonial, she used her influence to great effect. She promoted causes such as the education and empowerment of girls, the funding and celebration of the arts, and the protection of Icelandic nature, and oversaw a slew of legislation that made these goals possible.

She also had a role in possibly the most defining event of the second half of the twentieth century; the end of the Cold War. She hosted the Reykjavík Summit in 1986, which was a meeting between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev, about nuclear disarmament. While these talks did not result in any immediate arrangement, they showed that both sides were willing to meet, and what both sides were ready to concede on.

This was the first major step towards the dissolution of the Soviet Union. It was a very significant role for such a small country to play. It was, however, always part of Vigdís’s agenda to raise the profile of smaller nations and to aim for a world without the need for nuclear arms or NATO.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Laurentgauthier. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Laurentgauthier. No edits made.

Following her very successful presidency, Vigdís formed the Council of Women World Leaders in 1996. This is now one of the UN’s leading foundations, promoting female empowerment and gender equality around the world.

Numerous guided city walks, bike rides and segway tours around Reykjavík take you to the two main buildings that Vigdís Finnbogadóttir made history in. The first of these is the Office of the President of Iceland, which is located in central Reykjavík. The current president works each day in this building, and it is telling of how safe and open Iceland is that it is unfenced and has very little security. The second of these is Höfði House, the building in which Reagan and Gorbachev met for the Reykjavík Summit.

- See also: Iceland did it first in the world

- See also: Things to do in Reykjavík

Johanna Sigurdardottir

The final person on this list of the most famous Icelanders throughout the ages is the only one to make history in the 21st Century. Jóhanna Sigurðadóttir is not only notable for being the first female prime minister of Iceland, nor for pulling Iceland out of a financial crisis that threatened to destroy it; she was also the world’s first openly gay head of state.

The attitudes of Icelanders in regards to the LGBTQIA+ community* changed radically from the 1980s to the 2000s, going from hostility, to tolerance, to celebration. It became one of the first countries to recognise same-sex partnerships in 1996, and granted the community full adoption rights in 2006.

The election of a person in the queer community to lead the government, however, was an enormous landmark, and to this day, Jóhanna remains the only openly lesbian leader of any country throughout history. The trail she blazed, however, set a path for the gay men Elio Di Rupo, Xavier Bettel and Leo Varadkar to become prime ministers of Luxembourg, Belgium and Ireland respectively.

Jóhanna was a very successful prime minister, especially regarding the economy and social justice rights. She lifted Iceland out of its post-crash slump and strengthened trade unions to protect workers. Her actions radically changed the neo-liberal politics that had reigned under the 18 years of the government of the Independence Party.

She also accelerated Iceland’s path towards becoming a bastion of social justice. Her government passed marriage equality with a unanimous vote in parliament, and she and her partner became one of the first couples in Iceland to have an official same-sex union.

Furthermore, she promoted the rights and opportunities of women, most notably by leading Iceland to be the first country in the world to ban stripping; though not uncontroversial, she was adamant in the belief that no woman’s body should be used as a commodity for others to make money off.

Jóhanna retired from politics in 2013, opting not to run for re-election. Though only serving one term, she left the office of Prime Minister having changed the face of Iceland forever.

The Parliament building, or Althing, that Jóhanna used to preside over is located in the middle of the downtown area, besides the city’s humble and quaint cathedral. This is visited on most tours around the capital. To get a sense of the level of tolerance that allowed Iceland to elect a gay leader without any furore, visit during Reykjavík Pride, when about a third of the nation turns out on the city streets to celebrate queer culture.

*LGBTQIA+ is the acronym used by the National Queer Association, Samtökin ‘78, and is here used to refer to all sexual and gender minorities.

- See also: Gay Iceland - all you need to know

Honourable Mentions

As noted, there is no way to compile a list of famous historical Icelanders without leaving a few out. Here are some honourable mentions who just missed out on the list.

-

Ari Þorgilsson: As discussed earlier, without Ari Þorgilsson, almost all of our knowledge of medieval Iceland and the settlement era would be gone. Furthermore, because of his works, Icelanders can trace back their family histories for centuries, often to the 800s. He only misses out on the list as his works do not have enormous international influence.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, unknown author. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, unknown author. No edits made.

-

Guðrún Ósvífursdóttir: Guðrun is a character in the Laxdæla saga who is believed to have actually existed. A legendary beauty, she had four marriages, none of which ended well, and she ended up becoming the nation’s first nun. Although the first central female protagonist of any Icelandic story, however, she did not change the country in the same way that later women did.

Due to the customs of her time, the main reason she is so venerated is because of her beauty, rather than how she altered culture with her bold actions, so she just doesn't quite compare to figures such as Bríet.

-

Hans Jonatan: Hans Jonatan was the first person of colour to settle in Iceland. He was born a slave in the Caribbean, under Danish rule, before the family that ‘owned’ him moved back to their homeland. Here, he escaped, joined the Danish Navy, and was celebrated for his role in the Napoleonic wars.

When it was discovered who he was, however, he went to trial to consider whether or not he was legally a free man, as it was illegal to own slaves in Denmark outside of the colonies. The authorities cruelly ruled against him, and ordered he return to slavery in the Caribbean; once again, however, he escaped. The Danish records of him end here; but in the early 1990s, it was discovered what had happened.

He had fled to Iceland, where he was met with respect because of his good Danish language skills. He got a job in a trading station, which he would eventually take over the running of, married an Icelandic woman, and died a free man. He has about 900 living direct descendants, including an ex-prime minister.

While he did not change the history of the world like those who made the list above, he certainly changed Icelandic history and informed Icelanders of the time about the cruel realities of the distant rest of the world.

-

Sveinn Björnsson: Sveinn Björnsson was Iceland’s first president, following independence in 1944 when Denmark was taken over by the Nazis. Re-elected twice, his stern resolution meant that Iceland’s newly discovered nationhood was impossible to deny. Even when the Danish King revealed that he fully expected Iceland to remain part of his state following the end of the war, Sveinn was very clear that this was not the future his nation envisioned.

What makes him even more notable as a historical figure is his relation to the aforementioned Sigríður Tómasdóttir; he was the lawyer she was working with to try to save Gullfoss. While his role in the formation of the nation was enormous, however, he did not change culture in the same way those listed above did, so just misses out on a place on the list.

-

Björk: No discussion about famous Icelanders can be complete without at least a mention of the legendary musician and artist Björk. Since her time in the Sugarcubes, she has been redefining the music industry, the fashion world, and what it means to be creative. She has put Iceland on the map regarding contemporary culture and is well-loved across the nation.

The only reason she is not included on this list is because her career is still thriving; the full effect that she has had on Icelandic society, pop culture and the wider world is still to be determined.

-

The Icelandic Football teams: The Icelandic football teams also deserve to be mentioned here. While they have not yet won an international competition, they have represented Iceland with talents that no one was expecting over the past few years. During the UEFA European Championship in 2016, the world watched in awe as Iceland fended off challenger after challenger, knocking renowned footballing nations such as England out of the league.

They ended up reaching the quarter-finals and placing eighth. The winning team, Portugal, however, drew against Iceland in their first match. Iceland has now just become the smallest country ever to qualify for the FIFA World Cup.

The nation was ecstatic with their achievements, and Europe was in awe. While it was a mighty feat that drew the world’s attention, however, it was not the first time Icelandic footballers had wiped the floor with people’s expectations of them. In 2013 UEFA Women’s European Championship, the Icelandic team had also made it into the top 8. It is a shame it did not get such furore, but proved that the 2016 championships were not a fluke; Icelandic football is in its renaissance.

Iceland may be one of the world’s smallest independent countries, but FIFA considers its teams to be rising amongst the best in the world. As of March 2017, the men’s team was considered the 23rd best, and the women’s 18th.

- See also: The best of Bjork

- See also: Iceland's football team is back home

Many more individuals, from characters of the Sagas to the modern directors and composers, deserve a mention, just illustrating the depth of Iceland’s contribution to the world. No matter what field of study, there are Icelanders who have made a significant contribution to its understanding.

From Ingólfur Arnarson to Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir, the people of this little island nation have carved their distinct places in world history, and put Iceland on the map.

Otros artículos interesantes

Las Mejores Actividades de Invierno en Islandia

¿Cuándo es la estación de invierno en Islandia? ¿Cuáles son las mejores cosas que hacer en Islandia en invierno? ¿A qué actividades invernales te puedes apuntar? ¿Cuáles son los mejores tours y excurs...Leer más

Islandia en Otoño - La Guía de Viaje Definitiva

El otoño en Islandia es una época mágica en la que la naturaleza se cubre de variados colores, convirtiéndola en un momento ideal para conocer el país. Descubre paisajes increíbles, observa auroras bo...Leer más

Islandia en Primavera - La Guía Definitiva de Viaje

Islandia es un país de increíble belleza natural y la primavera es una de las mejores épocas para vivirla. Desde las auroras boreales hasta la migración de las aves, la primavera en Islandia es una...Leer más

Descarga la mayor plataforma de viajes a Islandia en tu móvil para gestionar tu viaje al completo desde un solo sitio

Escanea este código QR con la cámara de tu móvil y pulsa en el enlace que aparece para añadir la mayor plataforma de viajes a Islandia a tu bolsillo. Indica tu número de teléfono o dirección de correo electrónico para recibir un SMS o correo electrónico con el enlace de descarga.