Seal Watching in Iceland

Iceland is home to numerous seal colonies who can be easily spotted in many breathtaking locations around the country. Read more to find out everything you need to know about seals and seal watching in Iceland.

Photo above by Jane Yeo

- Learn all you need to know about Wildlife and Animals in Iceland

- Read about Whale Watching in Iceland

At the Jökulsárlón glacial lagoon, visitors marvel at massive icebergs, breaking from the tongue of a glacier and slowly making their way across a tranquil water's surface to the ocean.

It is a site of immeasurable beauty, drawing people from the world over, but for the local seals, it is home. Frolicking between the ice flows, riding in the surf along the Diamond Beach, or hauled out on the bergs, the pinnipeds make what is already a magical experience that much more charming.

While the glacier lagoon is an incredible seal-watching spot, it is by no means Iceland’s only, nor its best. With its rugged coastline, remote fjords and a wealth of beaches, Iceland offers some of the most readily available and rewarding seal-watching locations in the world.

Taking part in any coastal activity in Iceland provides a good chance of seeing these beautiful animals. On a best value kayaking tour in a fjord just outside Reykjavík, you might see them poking curiously around your boat, and scuba divers in the Westfjords can spot them gliding gracefully through the waters. Those eager for a great seal-watching experience from shore, however, need to look no further than the Vatnsnes peninsula in North Iceland.

Three locations, Svalbarðshreppur, Illugastaðir and Hvítserkur, are reliable for seeing seals year-round, ‘hauling out’ for hours a day as a way to regulate their body temperature after hunting in the icy waters of the North Atlantic. Harbour seals are the most common and the least wary of visitors, although grey seals, the only other species to pup on the island, are not at all uncommon.

Lucky travellers with a keen eye may even spot rogue visitors to Iceland. Harp seals, bearded seals, hooded seals and ringed seals, who usually reside in the Arctic, have all been spotted in local waters and on the shores. Very rarely, walruses are also seen; in fact, in the year 2013 alone, there were more recorded walrus sightings than there were in the early 18th Century. With rising temperatures and melting ice, it is only reasonable to expect more in the future.

The Icelandic Seal Centre

The growing interest in seal research and watching led to the establishment of the Icelandic Seal Centre back in 2006, which is located just on the Vatnsnes peninsula in a quaint fishing town called Hvammstangi. Almost 40,000 people visited the centre in 2016, and over 10,000 explored its exhibits. As of January 2017, the Centre is looking to at least double that record.

Within the building, one can learn about the species native to Iceland and the Arctic. Seal skeletons are on show with information on their anatomy, and there is a wealth of information on seals in Icelandic tradition, both within fables and within hunting traditions.

For those eager to learn more about these creatures or sharpen their skills regarding seal-watching, it is an essential stop on any tour of North Iceland. You can even choose from some great accommodations in Hvammstangi if you want to make the most of your visit.

Photo by Pascal Mauerhofer

Photo by Pascal Mauerhofer

While its exhibitions exist to inform and entertain, the Icelandic Seal Centre is also a vital research institution. Seals are still culled in Iceland to protect the fisheries, as it is believed that those that rest along estuaries are damaging to salmon populations. One aim of the Seal Centre is to determine whether this impact is enough to justify the cull and whether it is, in fact, more damaging to the ecosystem and economy to continue the tradition.

They also research the impact of tourism on seal populations, monitoring those on beaches accessible to visitors, and those where humans are not allowed to step; the results of this research are helping to build a sustainable and ethical seal-watching industry in the country.

Perhaps the most exciting of their endeavours, however, is the annual Seal Census. Alternating each year between July and August, the centre rallies a large group of volunteers - for which anyone can apply - to scour 80km of coast in the local area to determine how the population is changing and what factors are causing such changes.

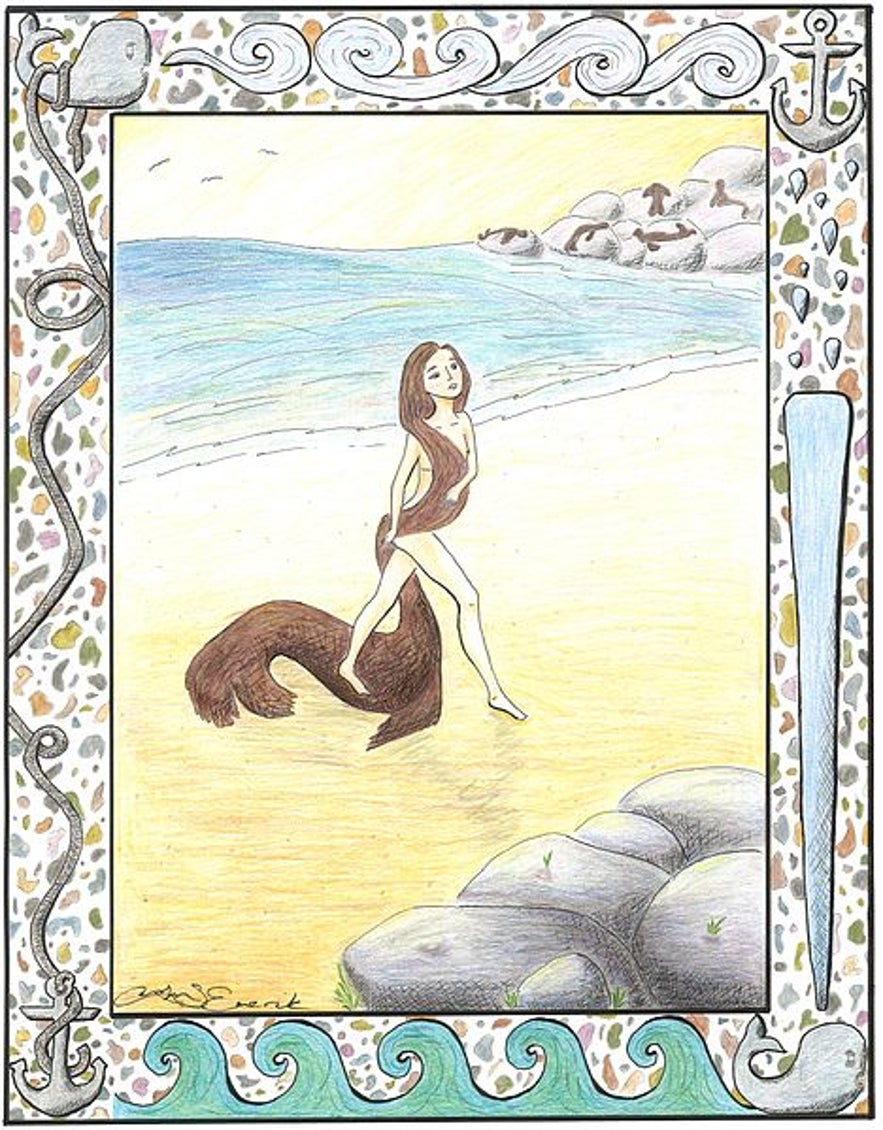

Seals and Icelandic folklore

Before Iceland’s industrial development, pinniped conservation was naturally low on the peoples’ agenda. In a nation with dark, long winters and little wood to burn, seal blubber provided invaluable fuel. Their fur could ward off brutally cold conditions, and their meat was plentiful enough to feed a family for weeks. Up to the 20th Century, therefore, their populations were in steady decline. That is not to say, however, that the intelligence and charm of seals was overlooked by native Icelanders.

There is a fable called ‘the Seal’s skin’ that has endured for centuries in Iceland. It is said that a fisherman discovered a cave with luxurious seal-skins at its mouth; out of sight, in the cave’s depths, he could hear dancing and singing, so he secretly stole one of the skins and locked it in a chest in his house.

On returning to the cave, however, he discovered a beautiful woman weeping. He clothed her and took her home, and though ever distant, and silent around others, she fell in love with him. The two married and had seven children, but the man never told her of the contents of his chest, always keeping the key in the pocket of his everyday clothes.

One Christmas, however, his wife was too sick to join him to a party, and when he walked off in his fineries, he left the key behind. The day he returned, she was nowhere to be found, and he discovered the chest open and the seal skin gone.

He never saw her again, but whenever he went fishing in the ocean, would find a lone seal, whose eyes always seemed to be running tears, circling his boat and driving fish into his net.

Their children also lost their mother that day, but whenever they walked along the seashore, would see the same creature swimming alongside them, tossing them pretty shells. Their last memory of her were the words that she whispered to them before disappearing; ‘Where have I to flee? I have seven kids on land, and seven pups in the sea’.

Photo by Angel Luciano

Photo by Angel Luciano

This tale of the skin-shedding seal, known as the Selkie, is not actually exclusive to Iceland. In the Faroe Islands, the same story exists, but most variations have it that the farmer sought out his wife after she left him, and killed her with her seal-husband.

Scottish and Irish folklore also have Selkies but represent them as beautiful and predatory rather than beautiful and forlorn. It is thus perhaps telling that Icelanders have always had a strange appreciation for the charm and beauty of seals, in spite of the fact that they were hunted to survive.

- See also: Folklore in Iceland

Interactions with seals in the modern era

As the country urbanised in the 20th Century, the hunting of seals became less necessary for survival and dropped. Before large populations could return, however, the 1960s brought back a trend amongst the wealthy for seal fur coats, which had not been so popular since the turn of the century.

Throughout the decade, around 6,000 a year were killed for the fashion industry. The conservationist movement of the 1970s brought this practice into sharp decline, but as of 1982, it was government policy to have ‘bounty’ on seals so that they would have less of an impact on fisheries. Nowadays, a few hundred are killed a year.

Aside from their habit of snapping up salmon as they swim upriver, seals are carriers of a ringworm that can be passed onto fish. Grey seals also have a habit of biting fish through nets to get at their livers, spoiling the catch and damaging equipment. Therefore, debate regarding how to marry conservation with Iceland’s second largest industry is ongoing in the country.

On the one hand, many argue that the seals are by no means endangered, and local hunting is no threat to the populations. While true, the Icelandic Seal Centre’s research has shown that the overall population is nowhere near as large as it once was, and is in fact shrinking. When compared to seal and sea lion colonies on the nearby Arctic ice and in other parts of the world, Iceland’s pupping and moulting grounds are small and very sparse.

Photo by Pascal Mauerhofer

Photo by Pascal Mauerhofer

While more urbanised Icelanders hold less stock in old traditions that may challenge modern international values, some coastal landowners claim that seal hunting is part of their heritage. Many argue that the sale of seal products, which remains legal in Iceland, is vital to their income.

The novelty of buying seal fur has an allure to some visitors, and as tourism has increased, there is some speculation that small-scale seal hunting is increasingly lucrative, and growing accordingly. Arguably similar to whaling, what was once a national tradition, needed for survival, may be thriving today due to foreign curiosity above local needs.

Visitors who seek to appreciate these creatures alive and in their natural habitat, therefore, should be careful of the products they are buying, lest they unintentionally lend their money to a side of the debate they do not agree with. If Iceland’s seal-watching can develop into an international attraction and a more significant part of Iceland’s booming tourism industry, then it is very likely that conservation will be better for the local economy than exploitation, and a change in values will follow.

- See also: History of Iceland

Responsible Seal Watching

Photo by Federico Di Dio photography

Photo by Federico Di Dio photography

There are many ways visitors can enjoy the seals without causing them stress or harm. When visiting a hauling ground by foot, slow movements and quiet voices are essential. A reasonable distance should be maintained, especially during the pupping season when mothers are likely to be more defensive; this occurs in the summer months for harbour seals and the late autumn for grey seals.

It is not unusual to be approached by the naturally inquisitive harbour seal, and even though this is rarely a sign of aggression, visitors are encouraged to move away from them for the safety of both.

Under no circumstances should they be touched; doing so can pass infections both ways. Feeding the animals is also strictly forbidden; seals that become reliant on human handouts will lose essential survival skills, venture into human areas that may be a danger to them, and may even develop unnaturally violent behaviour in search of an easy meal.

Photographing them is encouraged, as a wider circulation of images of these creatures in their beautiful natural habitat will help the seal-watching industry grow; just be careful not to use the flash as it may bother them. As a final note, bringing a dog to a hauling or pupping ground puts both animals in danger, and is strongly discouraged.

Photo by Pascal Mauerhofer

Photo by Pascal Mauerhofer

When watching seals from a boat, there are a few additional guidelines. Boats should move slowly, with the engine as quiet as possible, so not to be a disturbance. Whoever is steering should try not to separate any individuals in the water from the group they are with, as it may be seen as an aggressive action.

If seals on the beach are paying significant attention to the boat, it may be due to a wariness of the propellers, and they may avoid entering the water to escape injury. In such a case, the boat should be slowly moved away. Of course, regardless of whether or not there are seals, nothing should be thrown overboard.

Seals can be spotted anywhere along the Icelandic coast, at any time during the year; as noted, however, searching the Vatnsnes peninsula is likely to warrant the best results. The optimal viewing time to catch them on the shore is within two hours of low tide.

The Future of Seals in Iceland

Like basically every animal on earth, human activities and a rapidly changing climate mean the future of seals is uncertain worldwide. It is heartwarming to see, however, a concerted effort amongst Icelanders and visitors alike to celebrate and protect these creatures on this little island. Seals have been here for longer than any humans, and deserve the opportunity to thrive on the beaches they have always called home.

Seal-watching is an ever-growing industry, and with the help of the Icelandic Seal Centre, is becoming both safer for the pinnipeds and more enjoyable for people. If it can boom further, then it will put to bed old survivalist traditions, and enshrine these amazing animals as part of Iceland’s national identity. There are few other places in the world where you can see these beautiful creatures within such incredible settings, so visitors to Iceland should really make the most of the opportunities to coexist with them peacefully.

Otros artículos interesantes

Conduce por Islandia y pasa las mejores vacaciones

Conduce por tí mismo por Islandia para tener las mejores vacaciones. Aquí podrás obtener cinco consejos para disfrutar de la mejor experiencia en el país. Lee esto antes de planificar tu propio tour...Leer más

Tiempo, Clima y Temperatura de Islandia Todo el Año

Entérate de todo lo que hay que saber sobre el tiempo en Islandia. Siendo una isla de extremos, el tiempo no es una excepción. Conoce las temperaturas por mes, el tiempo durante cada estación, cómo el...Leer másMapas de Islandia

Encuentra el mapa de Islandia que buscas con estos 20 mapas de atracciones de Islandia. Hemos creado todos los mapas esenciales de las atracciones imprescindibles de Islandia en Google Maps para ayu...Leer más

Descarga la mayor plataforma de viajes a Islandia en tu móvil para gestionar tu viaje al completo desde un solo sitio

Escanea este código QR con la cámara de tu móvil y pulsa en el enlace que aparece para añadir la mayor plataforma de viajes a Islandia a tu bolsillo. Indica tu número de teléfono o dirección de correo electrónico para recibir un SMS o correo electrónico con el enlace de descarga.