Birds in Iceland

What are the most common birds in Iceland, and how do the birds connect to Icelandic culture and folklore? What season is best for birdwatching in Iceland, and where are the prime locations for birding? What birds can you expect to see in the city and what birds can you only see in the countryside? Continue reading for all you need to know about Iceland's wealth of avian life.

Birdlife in Iceland

Many travelers come to Iceland seeking to explore its thriving birdlife. As one can glean from seeing the various puffin statues on display in Iceland's gift shops, many visitors are excited about seeing the adorable Atlantic Puffins that nest on cliffs around the country. However, there are many other fascinating species of birds you can find in Iceland.

About 85 species of birds nest or are regularly spotted in Iceland, although about 330 species have been recorded visiting here since human settlement. While this number of different types of birds is relatively low compared to other European countries, the number of individuals more than compensates for this.

Take, for example, the birdwatching cliffs at Latrabjarg in the Westfjords. In the summer, there are millions of puffins and razorbills that nest there, meaning the sky is often thick with avian life.

It's not just coastal locations that boast such great birdwatching opportunities. Many different species can be seen in urban areas, including Reykjavik, especially around the downtown lake of Tjornin and the nature reserve at Seltjarnarnes.

These include the Arctic Tern, Greater Scaup, Tufted Duck, Gadwall, Common Eider, Common Ringed Plover, Whooper Swan, and many more.

Additionally, many other birds can be found around the country's many great lakes. The northern Lake Myvatn region, in particular, is a birdwatching paradise, with over fourteen species of resident duck amongst many other species. Furthermore, there are also birding opportunities in the highlands, moors and mountains, where there is even more biological diversity.

- See Also: The Ultimate Guide to Lake Myvatn

This article will discuss in depth some of the most unique and popular species of birds in Iceland and where you can find them on your travels.

Puffins in Iceland

First of all, we need to start with the bird Iceland is most famous for, the Atlantic Puffin. During nesting season between May to September, there are over seven million puffins in Iceland and a wealth of places around Iceland where they can easily be found.

As mentioned above, millions nest in the Latrabjarg birdwatching cliffs in the Westfjords, but even more can be found in the Westman Islands during puffin season. They have, in fact, become the signature symbol of the islands and are so common that it is a summer tradition for children to seek out and help lost pufflings that get attracted to the town's city lights.

While unmatched in terms of numbers here, Latrabjarg and the Westman Islands represent just the tip of the iceberg in terms of different puffin-watching locations.

- See also: Where to Find Puffins in Iceland

On the South Coast, thousands nest on the Dyrholaey cliffs, meaning those coming to see the dramatic arch the site is known for, are in for a pleasant surprise. Travelers to North Iceland, meanwhile, will find them in excess on the Tjornes Peninsula, which is otherwise known for its fossil-hunting opportunities.

The puffins of Iceland can also be seen from the main whale-watching destinations in the country: Reykjavik, Husavik and Akureyri.

It takes only a few minutes to sail from Reykjavik's Old Harbor on a puffin tour to the appropriately named Puffin Island and marvel at these adorable yet industrious birds. Even going on a whale-watching excursion from these locations can result in spotting puffins.

The puffin's charm is undeniable with its colorful beak and cute waddling when they walk around. Some people who only know them as adorable birds from pictures and postcards might wonder: can puffins fly?

In fact, they fly as far as 25,000 miles (40,000 kilometers) during their yearly migration period and spend most of their lives flying above and hunting in the sea. They only come to Iceland for nesting and can be found all around the country during that period. If you want to know more about where to see puffins in Iceland, read our article about it.

Golden Plover in Iceland

Photo from Wikimedia Creative Common by Brian Gatwicke. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia Creative Common by Brian Gatwicke. No edits made.

An Icelandic tradition dictates that when Golden Plover arrives, winter is over, and springtime is here. Every year a picture appears in the national newspapers of the first sighting of the 'lóa', indicating that winter is over, which normally happens between the 20th and 30th of March.

This colorful species of wading bird usually stays until late September, but individuals have been known to linger as long as the beginning of November. They can be found all around Iceland's freshwater bodies, such as in Lake Thingvallavatn in the south and Lake Myvatn in the north. Considering Iceland's extensive network of river systems, however, they are by no means bound to these locations.

- See also: Lakes in Iceland and Rivers in Iceland

No less iconic as a symbol for spring is the sound of their repeating chirp, familiar to any Icelander. It can be heard while traveling or hiking in the nature of Iceland and sometimes in towns and villages around the country, even if the plover itself can't be seen.

They only reside in Iceland throughout the summer months because their diet consists largely of worms, which they cannot reach when the ground is frozen in winter.

Ravens in Iceland

Perhaps the most significant bird of Iceland's history and culture is the Northern Raven. The raven is the only bird in Iceland that even has a friendly nickname, 'krummi' which referred to by Icelanders, rather than the more formal 'hrafn'.

There are countless poems and stories dedicated to the raven or using its appearance as a motif. Folk songs about the raven, such as ‘Krummavísur’ and ‘Krummi krunkar úti’ are known by virtually every Icelander.

Ravens have a special place in Icelandic folklore, dating back to the Old Norse beliefs of the first settlers of Iceland. Odin, the god of wisdom, had two ravens, Huginn and Muninn ('Thought' and 'Memory'), who traveled the world to gather information and whispered what they had learned in his ears.

Additionally, the first voyager who set out to find Iceland, and gave it its name, was Hrafna-Floki (Raven-Floki), who used ravens for navigation to find the island.

It is still said that if a raven allows you to stroke its feathers, it will whisper to you a secret of your future. A raven behaving noisily on a rooftop is supposed to be a warning that someone drowning, and one flying directly overhead either warns of death or promises prosperity, depending on its direction.

Being such an adaptable animal, ravens can be found all around Iceland. They are one of the few birds that remain in Iceland throughout the year and do not migrate in the winter.

- See also: Folklore in Iceland

Common Snipes in Iceland

The most recognizable characteristic of the Common Snipe in Iceland is not how it looks but the sounds it makes. During courtship, the male performs a 'winnowing' display by flying high in circles and taking shallow dives. This produces a drumming sound through the bird’s tail feathers vibrating, which many Icelanders have come to identify with summer.

This drumming sound is quite unique and has been compared to the bleating of a farm animal. That's why in many languages, the snipe is known by names such as the ‘Flying Goat’. In Icelandic, the sound has been compared more to the neighing of a horse. Therefore its Icelandic name - Hrossagaukur - translates to ‘Horse Cuckoo’.

Like other waders, the snipe prefers wetlands with plentiful insects and worms. While the draining and agricultural development of these areas in places such as England have depleted their numbers, the untouched nature of Iceland means they are still in great numbers here, throughout the lowland regions.

- See also: Iceland's Troubled Environment

Arctic Terns in Iceland

Arctic Terns are fascinating birds. No other animal species on earth has a longer migration route. These great flyers can travel up to 50,000 miles (80,000 kilometers) across the world in a year. Their breeding ground is in the Arctic North in countries such as Iceland during the summer, but when it gets colder, they travel south as far as South Africa or even Antarctica.

The average Arctic Tern will, in its lifetime, travel a distance that could take it to the moon and back three times, and as a species, it sees more sunlight than any other animal.

- See also: The Midnight Sun in Iceland

Throughout summer, they are abundant in coastal areas. Unlike birds such as puffins, they will not nest in cliffs but usually in simple burrows on flat ground. This is because their eggs do not need natural defenses, considering the fierceness with which both parents protect them.

The dive-bombing tactics of Arctic Terns are well-known in Iceland. Stray too close to a colony, and a scene straight out of Hitchcock's 'The Birds' tends to play out. As one, all the nesting birds will rise into the air, and unless you make a sharp exit from their eggs and younglings, they will proceed to swoop upon your head with their sharp beaks.

The dive-bombing tactics of Arctic Terns are well-known in Iceland. Stray too close to a colony, and a scene straight out of Hitchcock's 'The Birds' tends to play out. As one, all the nesting birds will rise into the air, and unless you make a sharp exit from their eggs and younglings, they will proceed to swoop upon your head with their sharp beaks.

While they can do little more than give you a good peck, the tactic works well as a deterrent for anyone getting too close. In places such as Greenland, their swooping attacks can even deter polar bears.

Arctic terns nest all around the coast of Iceland and have high populations in the southwest, including in Reykjavik, particularly around Grotta lighthouse on the Seltjarnarnes peninsula.

In recent years they've even been seen nesting at Hljomskalagardur park near the city center. There is also a notorious nesting ground at Jokulsarlon glacier lagoon, which many visitors inadvertently overlook, to their own peril.

Rock Ptarmigans in Iceland

Photo from Wiki Creative Commons by Marek Ślusarczyk No edits made.

Photo from Wiki Creative Commons by Marek Ślusarczyk No edits made.

The Rock Ptarmigan, much like the Common Raven, lives in Iceland throughout the year. But unlike the raven, it keeps itself far away from human settlements. A rather sedentary species, it prefers walking to flying and thus relies on its seasonal camouflage for protection.

In the summertime, its feathers are brown, but they turn white come winter.

The Ptarmigan is most relevant to Icelandic culture as a popular festive food often served as the main dish on Christmas Eve. Hunting season is usually in November each year, only for personal consumption, and all trade of the ptarmigan is banned.

- See also: Christmas in Iceland

Their main foods are berries, seeds, buds and insects, they are most often found in vegetated scrubland and prefer higher elevations than most other birds in Iceland. The Skaftafell Nature Reserve and Hrisey Island in North Iceland are particularly noteworthy for their colonies of ptarmigans.

Snowy Owls in Iceland

Photo by Christels

Photo by Christels

Rock ptarmigans are not just a festive meal for Icelanders. They are also the main food for Snowy Owls. These beautiful birds of prey are one of the nation’s most elusive animals, only being seen five to ten times a year, but definitely one of the most rewarding for birdwatchers to catch sight of.

They do not breed here because, due to the lack of rodents, Iceland is not a prime feeding ground for them. Their excellent camouflage against the snow makes them difficult to see, their silent method of flight does not draw attention, and the fact that they stay in Iceland during the dark months of the winter simply makes them difficult to spot.

When they are found, it tends to be in cold, remote reaches, such as in the East Fjords or the Highlands.

Gyrfalcons in Iceland

Tourism may imply that the national bird of Iceland is the puffin, and folklore may imply that it is the raven. However, the national bird of Iceland is actually the gyrfalcon and was even featured on Iceland's coat of arms in the early 20th century.

It still remains a symbol of Iceland, with the Falcon Cross being the highest honor the Icelandic state can bestow upon individuals.

The gyrfalcons are apex predators in the sky, having been used in falconry for centuries. Found across the Arctic region, Icelandic gyrfalcons are the most unique of the world’s populations, with a light, uniform plumage and a reputation for precision hunting, capable of reaching a speed of 130 mph (210 km/h) when diving on their prey.

For this reason, they were an important part of Icelandic trade with wealthy Europeans as far back as the medieval era, being one of the country’s most prized exports.

Like the Snowy Owl, they feed largely on ptarmigans but do not shy away from hunting other birds. They have been much more successful in Iceland than the owls, having a larger wild population. There are thought to be about 2,000 individuals in Iceland during the winter.

Due to the fact they nest in cliff faces, they are found most often in the Highlands, East Fjords, Westfjords, and mountainous parts of the North. In particular, they nest around Jokulsargljufur in the northern Vatnajokull National Park, a canyon that holds the most powerful waterfall in Europe, Dettifoss.

White-Tailed Eagles in Iceland

Photo from Wiki Creative Commons by Andreas Weith. No edits made.

Photo from Wiki Creative Commons by Andreas Weith. No edits made.

With a wingspan that can reach two and a half meters, White-Tailed Eagles are the largest bird in Iceland and undoubtedly one of the country's most impressive. They are a coastal species that prey on fish, rodents and smaller birds.

They have even been known to, much to the annoyance of farmers, prey on roaming lambs in the field.

White-Tailed Eagles are a great example of successful conservation efforts. Across Europe, they faced extinction in the late 19th century, but protective measures eventually reversed this decline in the following decades.

They went from barely twenty pairs before 1980 to over eighty pairs as of 2020.

While this work needs to be maintained for the eagle population to have a full recovery, Icelanders actively promote the interests of these animals.

To learn more about this species and the conservation efforts surrounding it, you can visit the White-Tailed Eagle Centre in the village of Reykholar in the Westfjords, which has a display dedicated to this majestic bird and sometimes helps nurse wounded eagles before releasing them back to the wild.

Those looking to spot the White-Tailed Eagles should look to the coastal regions of the West (including the Westfjords). It is not uncommon to even see them on boat tours from Reykjavik, particularly around Hvalfjordur.

- See also: Wildlife and Animals in Iceland

Whimbrels in Iceland

Photo by from WIki Creative Common by Marek Ślusarczyk. No edits made.

Photo by from WIki Creative Common by Marek Ślusarczyk. No edits made.

Whimbrels are classic waders, or ‘shorebirds’ in North American terminology, with their long, thin legs and beaks. Forty percent of breeding pairs nest in Iceland throughout summer, with around half a million individuals, though they largely spend their winters on the sunny coastlines of West Africa.

Iceland’s landscapes, particularly in the south, perfectly suit the lifestyle and habits of whimbrels. They tend to nest in flat moorland or tundra with low-lying vegetation away from human settlements and feed along coastlines and wetlands.

Considering Iceland is an island with many glaciers and river systems, feeding grounds are abundant for this long-legged bird.

Although their eggs, laid in relatively open land, are also vulnerable to predation by Artic Foxes, whimbrels will defend them with the ferocity of Arctic Terns. They have also been known to divebomb people who get too close, in spite of their reclusive nature.

Despite its habitat being on Iceland's shores, the whimbrel can occasionally be spotted in Reykjavik.

BONUS: The Great Auk in Iceland

All of the birds featured above can be spotted somewhere in Iceland, though some are harder to find than others. The Great Auk, however, can not be spotted in Iceland as it went extinct in 1844.

The last two confirmed specimens of this great bird were killed on the island of Eldey off the coast of the Reykjanes peninsula in Iceland. Nevertheless, it deserves its place among the birds of Iceland as it was a part of the country's history for centuries.

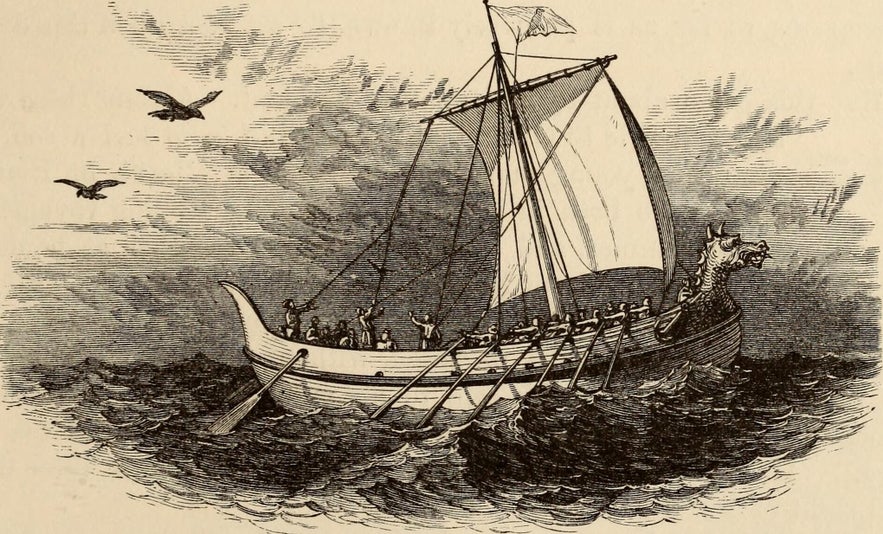

Illustration from Wiki Creative Commons, by John James Audobon. No edits made.

Illustration from Wiki Creative Commons, by John James Audobon. No edits made.

This flightless bird had a habitat widely along the shores of Western Europe, Iceland, Greenland, and on the east coast of Canada and is estimated to have had a population of over one million at its height. The Great Auks were talented swimmers and their main food was fish.

Since they were large birds that couldn't fly, it made them easy and bountiful prey for humans for a long time, with their bones having even been discovered among Neanderthal remains.

In the 19th century, these birds were known to have been very rare and sought after by collectors and museums, and some 70 taxidermy specimens exist today, one of them belonging to the Icelandic Museum of Natural History.

There are also two memorials dedicated to the Great Auk to commemorate the last pair of the species having been in Iceland.

One is located on the shores of Reykjavik near the domestic airport by Icelandic artist Ólöf Nordal. The other is located on the Reykjanes peninsula by American artist Todd McGrain, close to where the last pair of Great Auks were killed.

Great Auk Memorial in Reykjavik. Photo by Sigurður Árni Þórðarson

Great Auk Memorial in Reykjavik. Photo by Sigurður Árni Þórðarson

The memory of the Great Auk is important to hold up to remind people of the importance of the conservation efforts being administered to the birdlife that is currently thriving in Iceland.

What is your favorite bird in Iceland? How was your puffin-watching experience? Are there any birds we missed? Log in to Facebook to see or add to the comment section below!

Inne interesujące artykuły

Atrakcje południowej Islandii | Kompletny przewodnik

Jakie są najbardziej popularne atrakcje, które można znaleźć na południowym wybrzeżu Islandii? W jakich aktywnościach można wziąć udział? Jak długo zajmuje dotarcie tam ze stolicy, Reykjaviku? Czy m...Czytaj więcejIslandia we wrześniu | Wszystko, co musisz wiedzieć

Dowiedz się wszystkiego, co musisz wiedzieć o zwiedzaniu Islandii we wrześniu. Jeśli zastanawiasz się, jaka jest pogoda, co robić i jakie są najlepsze wycieczki, w których warto wziąć udział, to mam...Czytaj więcej

18 rzeczy do zrobienia i miejsc do odwiedzenia na Islandii

Dowiedz się o najlepszych rzeczach do zrobienia na Islandii i przeczytaj o tym, gdzie pojechać i co zobaczyć. Niezależnie od tego, czy chcesz podziwiać cuda natury, zanurzyć się w lokalnej kulturze...Czytaj więcej

Pobierz największą platformę turystyczną na Islandii na telefon i zarządzaj wszystkimi elementami swojej podróży w jednym miejscu

Zeskanuj ten kod QR za pomocą aparatu w telefonie i naciśnij wyświetlony link, aby uzyskać dostęp do największej platformy turystycznej na Islandii. Wprowadź swój numer telefonu lub adres e-mail, aby otrzymać wiadomość SMS lub e-mail z linkiem do pobrania.