Icelandic Food: The Ultimate Guide to Iceland Food Culture

- What Do They Eat in Iceland?

- Best Place to Try Icelandic Food

- Traditional Icelandic Fish and Seafood

- Hardfiskur - Stockfish

- Plokkfiskur - Fish Stew

- Humar - Icelandic Lobster

- Icelandic Bread

- Laufabraud - Leaf Bread

- Flatkaka - Rye Flatbread

- Rugbraud - Icelandic Rye Bread

- Icelandic Pastries and Sweet Bread

- Kleina

- Snudur

- Ponnukokur - Icelandic Pancakes

- Vinarbraud - Icelandic Viennoiserie

- Icelandic Lamb

- Hangikjot - Smoked Lamb

- Islensk Kjotsupa - Icelandic Meat Soup

- Pylsa - Hot Dog

- Traditional Food in Iceland

- Skyr

- Skata - Fermented Skate

- Slatur - Icelandic Liver Pudding

- Hakarl - Fermented Shark

- Svid - Boiled Sheep Head

- Hrutspungar - Pickled Ram Testicles

- Icelandic Sweets and Confectionery

- Icelandic Ice Cream

- Lakkris - Icelandic Liquorice

- Icelandic Alcohol

- Brennivin

- Icelandic Liquor

- Icelandic Craft Beer

- Modern-Day Icelandic Food

What to eat in Iceland? Read this comprehensive overview of Icelandic food culture and learn about all the different food you can try while visiting Iceland. What are the key characteristics of Icelandic cuisine? What food is Iceland known for? Read on and learn about the ingredients that make this nation's cuisine special.

In the past, resources in Iceland were scarce because of harsh winters and barren soil. Therefore, Iceland’s food culture is rather simple and has an emphasis on making use of what's available. With the modern conveniences of the 21st century, Iceland has gone through a cuisine revival in the last couple of decades, with Icelandic chefs re-discovering the possibilities of fresh local ingredients with a nod to the past.

The bountiful North Atlantic Ocean surrounds Iceland, and the country is blessed with fresh water and a clean natural environment. With new technology and renewable geothermal energy, freshly grown, locally sourced ingredients can be enjoyed year-round. However, Iceland’s traditional food remains popular with locals and visitors alike.

To learn more about the cuisine, you can book a wide range of food tours in Iceland with a local guide, taking you from place to place to try different foods.

All customers of Guide to Iceland can claim great discounts and special offers at many restaurants around the country by using the exclusive VIP Club, so make the most of it by trying out different flavors!

You will find a wealth of great restaurants in Iceland's capital, so make sure to book accommodations in Reykjavik if you want to dive into the country's food culture. To get around the city, we recommend renting a small budget car to drive within Reykjavik and into the countryside.

- Discover the Best Restaurants in Reykjavik

- See also: Best Restaurants in Iceland

What Do They Eat in Iceland?

The most typical Icelandic food is fish, lamb, or Icelandic skyr. These have been the main elements of the Icelandic diet for over a thousand years.

Icelandic meals are commonly meat-based due to the lack of farmable lands in the past. But geothermally heated greenhouses make vegetables more accessible, allowing modern chefs to be more imaginative and infuse new ingredients into old recipes.

Read on to discover traditional Icelandic food and what to eat in Iceland of you want to get to know the character of the country.

Best Place to Try Icelandic Food

Trying Icelandic food is a fantastic way to dive into the local culture, and there are plenty of restaurants that serve all kinds of traditional dishes. One of the best places for this is Hressingarskálinn, or Hressó, in downtown Reykjavik, which was originally opened in 1932.

Trying Icelandic food is a fantastic way to dive into the local culture, and there are plenty of restaurants that serve all kinds of traditional dishes. One of the best places for this is Hressingarskálinn, or Hressó, in downtown Reykjavik, which was originally opened in 1932.

Hressó serves a variety of local favorites, and you can try both loved homestyle meals like breaded lamb chops and meat soup or go for the more peculiar fermented shark and sheep head. They offer a reasonably priced two- or three-course menu, or you can order a tasty sharing pan with a generous serving of cod, bacalao, or pan-fried salmon.

Hressó is located on the lively Austurstraeti street close to many major attractions. Its cozy, welcoming atmosphere, with both traditional and modern dishes, makes it the perfect spot to dive into Iceland’s culinary scene. It's a popular spot, so make sure to book your table at Hressó ahead of time.

Traditional Icelandic Fish and Seafood

As an island nation, nothing has been more vital to the people's survival than fish. Fish is an integral part of Icelandic culture and heritage and a staple of traditional Icelandic food.

As an island nation, nothing has been more vital to the people's survival than fish. Fish is an integral part of Icelandic culture and heritage and a staple of traditional Icelandic food.

Fishing not only put food on the table, but exports also helped transform the country from one of the poorest in Europe at the beginning of the 19th century to one of the wealthiest today.

- See also: Fishing in Iceland

- Check out the Best Seafood Restaurants in Reykjavik

As refrigeration methods improved, fresh fish became more and more noticeable in the nation’s diet. In the 1950s and 1960s, Icelanders still ate fish every day, with some opting for this ubiquitous staple even for breakfast. Today, Icelanders eat fish on average twice a week, and over half of the population consumes fish oil, or "lysi," at least four times a week.

Pictures of fish decorate Icelandic coins, and the country has even fought wars over fishing rights. Fish has been Iceland’s typical food from its founding until today and will likely remain so in the future.

Most restaurants in Iceland serve a "fish of the day." The country is dotted with numerous seafood restaurants, mainly serving cod, haddock, salmon, and monkfish. Modern chefs in Iceland are masters at creating excellent dishes, infusing the ocean’s bounty with herbs and spices found in Icelandic nature. You can find many great fish dishes and traditional Icelandic foods in Reykjavik. But aside from a great meal at a restaurant, you should try out the following foods.

Most restaurants in Iceland serve a "fish of the day." The country is dotted with numerous seafood restaurants, mainly serving cod, haddock, salmon, and monkfish. Modern chefs in Iceland are masters at creating excellent dishes, infusing the ocean’s bounty with herbs and spices found in Icelandic nature. You can find many great fish dishes and traditional Icelandic foods in Reykjavik. But aside from a great meal at a restaurant, you should try out the following foods.

Hardfiskur - Stockfish

Hardfiskur or stockfish is flattened fish that is hung on wooden racks by the foreshore to be dried by cold air and wind. That gives it a storage life of several years, making it highly valuable for sustenance before the invention of refrigeration. It is available at any grocery store or the Kolaportid Flea Market. They’re eaten as snacks straight out of the bag or with butter spread on them. Although people don’t eat it quite as much today, stockfish remains a staple and popular traditional food in Iceland.

Before the turn of the 19th century, grain was hard to come by in Iceland. It needed to be imported from Denmark, making it too expensive for most Icelanders. Whatever grain or flour they could get was put in gruel to make it last longer, and bread was considered a luxury.

Before the turn of the 19th century, grain was hard to come by in Iceland. It needed to be imported from Denmark, making it too expensive for most Icelanders. Whatever grain or flour they could get was put in gruel to make it last longer, and bread was considered a luxury.

This scarcity meant that instead of eating a piece of bread with a meal, as was customary in neighboring countries, Icelanders ate dried stockfish. The stockfish was such a prominent symbol for Iceland in years past that from the 16th century until 1903, a crowned stockfish was featured on Iceland's coat of arms, as seen below.

Plokkfiskur - Fish Stew

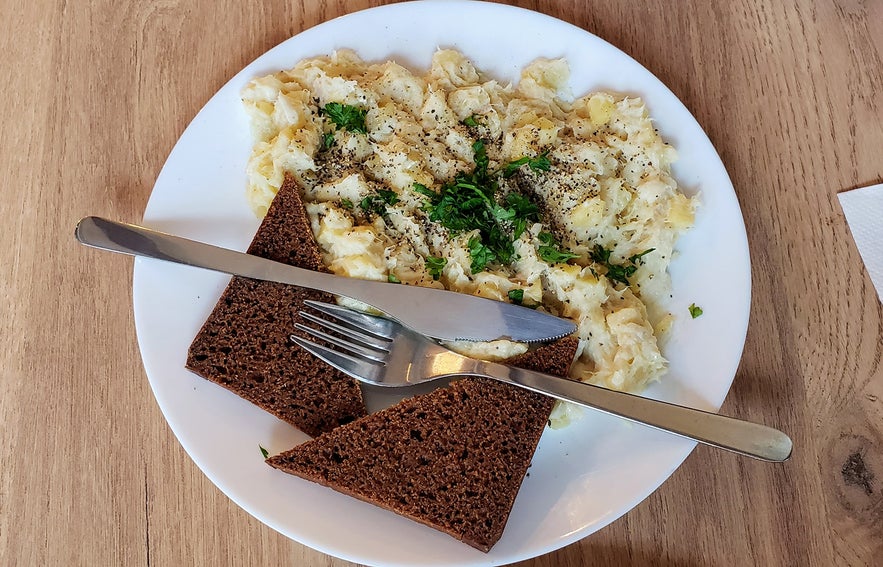

"Plokkfiskur" is an Icelandic fish stew made from a simple mix of white fish, potatoes, onions, flour, milk, and seasoning. Recently, some recipes have also included chives, curry, bearnaise sauce, or cheese. Plokkfiskur is traditionally served with a side of rye bread with butter.

"Plokkfiskur" is an Icelandic fish stew made from a simple mix of white fish, potatoes, onions, flour, milk, and seasoning. Recently, some recipes have also included chives, curry, bearnaise sauce, or cheese. Plokkfiskur is traditionally served with a side of rye bread with butter.

Plokkfiskur is an example of an old recipe, using basic ingredients that were available in most households during the early 20th century. It has recently been revived, with many creative chefs offering their own unique spin on this classic, which you can try at various food spots around town.

Humar - Icelandic Lobster

"Humar" refers to Icelandic lobster or langoustine. They’re usually caught in the waters by the South Coast, and these langoustines are known for their tasty, tender meat. You can find it grilled, baked, fried, or even as a pizza topping.

The most popular way to try Icelandic langoustine is, however, in soup. The Icelandic "humarsupa" is a delicious lobster soup served with a side of bread and makes for a delicious starter before engaging on a journey through Icelandic cuisine at a great restaurant.

Photo from Private 3-Hour Food Tour of Reykjavik

Photo from Private 3-Hour Food Tour of Reykjavik

Icelandic Bread

The settlers in Iceland were stubborn folks, which was perhaps necessary when living in a land of fire and ice. For centuries, the people tried living their lives as they would back in Scandinavia, as a pastoral society, raising cattle and sheep and growing grain to harvest for bread and fodder.

The farming methods of Vikings significantly impacted the Icelandic landscapes as wide-scale erosion began along with deforestation, which left much of the country barren. Therefore, little could grow in Iceland except for a few hearty vegetables like potatoes, turnips, carrots, cauliflower, and cabbage — but almost no grain.

Iceland was never a self-sufficient grain-producing country again. In some places, barley could be grown, but the yield was often meager due to the Icelandic weather.

After a period known as the "Little Ice Age," almost all grain cultivation in Iceland disappeared. It wasn’t until the 20th century that grain farming began again, with barley making up most of the grain harvest. But today, you can also find a few oat farmers around. As virtually no grain grew in Iceland, it had to be imported, making it very expensive.

Ovens were almost unknown due to a lack of firewood. So, the only people who could afford bread were very wealthy. In fact, the country didn’t have a professional baker until the early 19th century. Despite the lack of grain, ovens, and bakers, Icelanders still have a few signature bread varieties that remain popular today.

Laufabraud - Leaf Bread

Many families make "laufabraud," or leaf bread, before Christmas. It’s a very thin, round flatbread decorated with leaf-like geometric patterns. Families spend time creating beautiful patterns in the bread before quickly frying it in a pan. They then serve "laufabraud" with butter during Christmas dinner. Due to its close association with the holiday, it’s also known as Icelandic Christmas bread.

- See also: Christmas in Iceland

Flatkaka - Rye Flatbread

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Jonathunder. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Jonathunder. No edits made.

Another traditional bread is "flatkaka," a thin, round rye flatbread with a distinct pattern. The tradition of baking "flatkaka" is believed to go back to the age of settlement (around 1000 AD) when it was baked on hot stones or straight on the fire’s embers.

This method helped create the bread’s signature spotted pattern. However, later, small but heavy cast iron frying pans were used instead.

Today, these types of bread are usually spread with butter and topped with a slice of smoked lamb, which makes for a nice afternoon meal.

Rugbraud - Icelandic Rye Bread

If you visit the country, don't forget to try Icelandic rye bread or "rugbraud," a dark, sweet-tasting bread with a thick consistency and no crust. Tradition dictates it’s baked in a pot placed on the embers of a dying fire, then covered in turf and left to stand overnight.

Another way to make "rugbraud" is to bury the pot near a hot spring and let the geothermal heat bake the bread as seen in the video above. When this method is used, the bread is usually called "hverabraud" or hot-spring bread. You can try this geothermally baked bread on a geothermal culinary tour from Fontana Spa near the Golden Circle.

Rugbraud is perhaps best paired with fish (and an essential side with the aforementioned "plokkfiskur" fish stew), but you can also eat it on its own. Both "rugbraud" and "flatkaka" are delicious topped with mutton pate, butter, cheese, pickled herring, or smoked lamb.

Icelandic Pastries and Sweet Bread

In the 19th century, sugar was introduced to the Icelandic diet, and for years, it was considered necessary nutrition. At that time, ovens were more common, and even a few bakers were around.

When visiting Iceland, the traditional "flatkaka" and "rugbraud" bread are must try's, but you should also go to a bakery or a cafe to try the following modern(-ish) sweetbreads.

Kleina

Kleina is made of deep-fried flour dough, which makes it slightly crispy on the outside but soft and delicious on the inside. Its twisty shape prevents it from becoming doughy in the center because when it's being fried, it gets cooked evenly. The legend says it was created when a boy accidentally dropped a piece of dough in a pot of hot grease. It is popular in Scandinavia and Germany during Christmas time, but in Iceland, is served year-round! If you book a table at Saeta Svinid Gastro Pub, they serve great kleinas as a dessert!

Snudur

"Snudur" is the Icelandic version of a cinnamon roll. Its large size may intimidate people, but don't worry, you can just eat half of it and save the rest for later.

The roll is most often covered with glaze on the top and comes in three varieties. A classic pink glaze, chocolate glaze, or caramel glaze. Whatever glaze you choose, make sure to pick a snudur with plenty of it, as it can vary from snudur to snudur. Many modern bakeries make their own unique version of snudur, with various taste incorporated into the roll such as vanilla, blueberries and even licorice!

Ponnukokur - Icelandic Pancakes

Icelandic pancakes aren't really your typical pancakes served at breakfast and covered in syrup; rather, they are thin crepes usually served rolled up with a good amount of sugar (as seen above) or carefully folded with rhubarb jam and whipped cream.

These are very popular for an afternoon family gathering, paired with either a black cup of coffee or a cold glass of milk.

Vinarbraud - Icelandic Viennoiserie

Vinarbraud can be quite large, and usually way too big for just one person. Therefore they are usually served as slices, where each guest at the gathering can cut a slice that's just right for them.

- Learn more: The Best Bakeries in Reykjavik

Icelandic Lamb

Photo from Guided 3-Hour Reykjavik Food Lovers Walking Tour

Photo from Guided 3-Hour Reykjavik Food Lovers Walking Tour

Along with the fish, sheep have been the lifeblood of the nation since it was first settled in the late 9th century. Its wool has kept the people warm, and its meat has helped keep Icelanders alive through severe weather conditions.

The original settlers imported these animals, which have since been raised and bred in total isolation, unaffected by other breeds. Therefore, Icelandic sheep are sometimes called the "settlement breed."

Though famous for its wool used in lopapeysa wool sweaters, the Icelandic sheep are mainly farmed for their meat. Each spring, the sheep are let out of their pen to roam freely around the countryside, spending the whole summer grazing in the pesticide-free wilderness.

Since the climate prevents grain growth, the sheep live on grass, angelica, berries, and seaweed. The meat thus requires little seasoning; it’s tender and has a mild flavor. Smoked, grilled, broiled, slow-cooked, in a kebab or a stir fry, you can find numerous Icelandic lamb variations throughout the country.

And as with the seafood, whatever you choose will surely be delicious.

- Learn more: Icelandic Sheep: The Ultimate Guide

Hangikjot - Smoked Lamb

Photo by Martin Christensen, Wikimedia Creative Commons. No edits made.

Photo by Martin Christensen, Wikimedia Creative Commons. No edits made.

Though you can find fresh meat in grocery stores and on restaurant menus, a popular Icelandic food to taste is smoked Icelandic lamb or "hangikjot." Before refrigeration, smoking was a standard method used to preserve food. It not only allowed the meat to last, but it also added flavors.

Hangikjot, literally meaning "hung-meat," is named after the old tradition of smoking the meat by hanging it from a smoking shed’s rafters. There are two main smoking methods in Iceland, "birkireykt" and "tadreykt."

The material used in "birkireykt" is birch wood, while dried sheep dung is mixed with hay for "tadreykt." It’s not just "hangikjot" that is smoked this way. You can also find "tadreykt"-smoked salmon, sausages, and even beer.

"Hangikjot" is usually boiled and served either hot or cold in slices. It’s a traditional dish served at Christmas, usually accompanied by potatoes in "uppstufur" sauce, green peas, red cabbage, and "laufabraud."

According to a recent study, around 90 percent of Icelanders eat this dish at least once during the holiday season.

A great Icelandic lunch choice is the "hangikjot" sandwich. The smoked lamb is thinly sliced and used as lunch meat served on sandwiches or traditional "flatkaka" bread.

Islensk Kjotsupa - Icelandic Meat Soup

"Kjotsupa" is made of tougher bits of lamb, hearty vegetables, and various Icelandic herbs. Great on a cold winter’s day and a quick lunch option in cafes and restaurants.

"Kjotsupa" is made of tougher bits of lamb, hearty vegetables, and various Icelandic herbs. Great on a cold winter’s day and a quick lunch option in cafes and restaurants.

In years past, sheep meat (as opposed to leaner lamb meat) was cut down and served in soup with sour milk, accompanied by some type of cereal such as barley, when vegetables were rare in Iceland. Sometimes skyr would even be added to the soup for taste. However, in the late 19th century, Iceland benefitted from world trade routes and started adding hearty vegetables such as potatoes and carrots in the soup, and from there, it evolved into the much-beloved classic it is today.

Pylsa - Hot Dog

Photo from Small-Group 3-Hour Traditional Icelandic Food Tour in Reykjavik

Photo from Small-Group 3-Hour Traditional Icelandic Food Tour in Reykjavik

Also spelled "pulsa" and often listed as the top thing to eat in Iceland, it’s made from a lamb, beef, and pork blend. Try "ein med ollu" (one with everything), and you’ll get the famous Icelandic hot dog with crunchy deep-fried onions, raw onions and topped with ketchup, sweet mustard, and creamy remoulade sauce.

Traditional Food in Iceland

Although you can find a whole range of culinary delights in Iceland, the nation has not forgotten the old ways of preparing food. Today, you can find traditionally cured meat in grocery stores and restaurants. Once a year, the midwinter festival Þorri is celebrated all over the country with feasts of traditional food, which was popular throughout Iceland's history.

People often think of the traditional style of curing meat when they hear "Icelandic food." And it does sound scary. Fermented shark, pickled ram's testicles, and boiled sheep heads don't sound like things you put on a dinner plate. But these methods of preparing food were done out of pure necessity.

Fresh food from Iceland was rare during the winter, so to survive in this desolate and harsh environment, the people had to preserve their food. Before refrigeration, methods like salting were used worldwide to preserve food. To produce salt from the ocean, you need to let the water evaporate.

Evaporation can be achieved by letting the water sit out in the sunlight or placing it over a fire. However, Iceland has precious little sunlight and even fewer trees to burn. The lack of vegetation also meant that animal products dominated Icelandic cuisine, and poverty prevented any part of the animal from being thrown away.

The meat and offal were preserved through the winter by using methods like pickling in lactic acid, fermented whey or brine, drying, or smoking, which gave the traditional country food its distinct flavor.

Thankfully, modern technology has replaced these old methods of storing food. However, many holidays are still centered around consuming these traditional foods in Iceland. Although some might look (and smell) scary, not all traditional Icelandic food tastes bad.

At "Thorrablot" gatherings, you’ll always find "hardfiskur" stockfish, "hangikjot" smoked lamb and "skyr," "rugbraud" and "flatkaka." If you're feeling adventurous, you should definitely try some of these Icelandic foods.

Skyr

Dutch journalist Anita Joachim enjoys a bowl of skyr with sugar and cream during a visit to Iceland in 1934.

If you visit the National Museum of Iceland, you can see three jars filled with what appear to be gray rocks. They’re a leftover meal of "skyr" from over a thousand years ago. "Skyr" is a traditional dairy product that resembles yogurt but is technically classified as cheese. When Vikings settled here, they brought with them the culinary traditions of their homeland.

These Norse dishes have evolved differently in each country, with each nation having its own variation. But "skyr" seems to have vanished entirely in Scandinavia while flourishing in Iceland. Today, you can even find it on shelves of grocery stores around the world.

The product is made by separating skim milk from the cream. The milk is then pasteurized, and live cultures from previous batches of "skyr" are added. When the product thickens, it’s filtered, and various flavors are added, like vanilla or berries and, more recently, mango, coconut, and even licorice.

It’s a traditional Icelandic breakfast choice but can be enjoyed as a meal at any time of the day. They go especially well with blueberries, giving you a great blend of protein and antioxidants.

If you want to learn more about this important dairy product in Iceland's history, book tickets to the Skyrland Exhibition in Selfoss. It's an interactive museum dedicated to Skyr, appropriately called Skyrland.

Skata - Fermented Skate

"Thorlaksmessa" (Thorlac's mass) is a celebration held the day before Christmas Eve. During that day, a fermented skate (a type of ray) is served with potatoes and tallow, and some Icelanders insist that Christmas doesn’t start until the dish is eaten.

Some don’t even mind the strong ammonia-infused odor that accompanies it, while others (understandably) avoid it like the plague. The taste, however, isn’t as strong as the smell, reminding some of the salted cod. However, getting past the smell is quite a challenge.

- Read more about Icelandic Christmas Traditions

Slatur - Icelandic Liver Pudding

Photo by Navaro, Wikimedia Creative Commons. No edits made.

Slatur is a liver pudding that is regularly eaten in Iceland year round. It’s not uncommon for modern Icelandic families to get together and make their own "slatur" before a "Thorrablot." They make it from sheep’s blood or liver and kidneys, minced fat, oatmeal, rye, and spices.

There are two versions of slatur, "blodmor" which is a type of black pudding that has been eaten in Iceland since settlement times, and "lifrarpylsa" is a liver sausage that's similar to haggis,

"Slatur" is usually served with boiled potatoes and mashed turnips, and the leftovers go great with rice pudding topped with cinnamon.

Hakarl - Fermented Shark

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Chris73. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Chris73. No edits made.

"Hakarl" is a fermented Greenland shark. These are poisonous when fresh as they contain a deadly amount of ammonia, but they are safe to eat after being buried in a hole to ferment for six weeks (and up to 12 weeks).

It’s then hung to dry for four to five months and then served in cubes. This peculiar method of preparing a meal is age-old, and its exact origins are not clear, but it's been used in Iceland for centuries.

In recent years it has become customary to drink a shot of Brennivin (Iceland's national spirit) after eating Icelandic fermented shark to help get rid of the flavor.

Svid - Boiled Sheep Head

"Svid" is a boiled sheep head, usually cut in half with the brains removed and hair singed off. It doesn’t taste as bad as it looks (or sounds?) and is usually found in buffets served during the mid-winter festival.

However, Icelanders eat the eyes and tongue as well. The ears aren’t eaten because it’s associated with theft. The tradition was born out of not wasting any part of an animal when food was scarce.

Hrutspungar - Pickled Ram Testicles

"Hrutspungar" is pickled ram's testicles - boiled and cured in whey. There’s also a pate version that is easier to the stomach and can be spread on rye bread.

Icelandic Sweets and Confectionery

What do people in Iceland eat as a treat? Did you know that sugar was not available in Iceland until the late 19th century? From 1880, shortly after sugar importation began, and up until 1950, sugar consumption in Iceland increased by over 710 percent. It appeared to be love at first sight (or taste).

Icelandic Ice Cream

It doesn’t matter if it’s the dead of winter with freezing wind blowing and snow falling from the sky - Icelanders will still eat ice cream. You can find an ice cream parlor in almost every town in Iceland, with many located near a geothermal swimming pool, where it’s a popular treat after a swim.

Soft-serve ice cream is the most popular kind. But don't just get plain ice cream. Dip it in a hard-shell dip, usually made of chocolate, and then cover it in small-sized candy.

If you want to go extreme, order a "bragdarefur." This is when soft ice cream, usually vanilla, is put in a large container, though some places offer other varieties. You’ll then choose three types of candy and or fruits on display at the parlor’s counter. The whole thing is then put in a large mixer, more candy is added on top, and voila! You’ll have the ultimate Icelandic ice cream treat.

- Where to go: The Best Ice Cream Parlors in Iceland

Lakkris - Icelandic Liquorice

Browsing the candy aisle in supermarkets, you’ll notice that many Icelandic sweets contain salty licorice or "lakkris." The most popular kind is chocolate-covered licorice, but you can also find strange combinations like licorice-powdered raisins, dates, and almonds.

Of course, there’s licorice ice cream, which you can dunk in hard-shell licorice dip and cover with licorice powder (although most would agree that’s a bit overkill). This salty black treat has even made its way from the candy aisle into regular food. There’s licorice salt, licorice mustard, licorice sauce for lamb, and even licorice cheese.

The obsession began a few centuries ago when licorice was introduced to Iceland by Scandinavians. Icelanders had no honey and no sugar, so this root was used to satisfy the country's sweet cravings. The root was also believed to help with colds, so it was used by Icelandic pharmacists who added it to cough syrups and lozenges to combat various ailments.

In the early 20th century, wars and import restrictions deprived the country of foreign sweets. Therefore, Iceland manufactures its own sweets, often using (you guessed it) licorice.

You can get foreign sweets in Iceland, but the Icelanders still prefer their salty candy. So, when visiting the country, "lakkris" is something you should try.

Here are some of the nation’s favorites:

-

Draumur and Thristur - chocolate-covered licorice bars.

-

Opal - licorice lozenges that have been around since 1945.

-

Appolo Stjornurulla - a liquorice and marzipan roll.

-

Lakkrisror - a licorice straw used to drink soft drinks.

-

Gammeldags Lakrids - pure, salty liquorice.

Icelandic Alcohol

The Icelandic settlers drank mead and ale, and for centuries, it was the most popular alcoholic drink in the country. When grain production in Iceland was dying down in the Middle Ages, imported beer became popular.

However, after importation restrictions from Denmark (who ruled Iceland at the time), it became cheaper to import schnapps and vodka, which became the drinks of choice for Icelanders. At the turn of the century (1900), attitudes toward alcohol shifted, and a prohibition on all alcohol took place in 1915. The ban was partially lifted in 1921, thanks to Spain.

At the time, Iceland’s biggest export was salted cod, and Spain threatened to stop importing the product unless Iceland imported Spanish wine. Therefore, the ban was amended, allowing red wine and rosé from Spain and Portugal.

However, it didn't take long for people to undermine prohibition. People smuggled alcohol into the country, and they passed around a popular home-brewed drink known as "landi." Doctors would even prescribe patients alcohol, with wine for the nerves and cognac for the heart.

In 1935, spirits and all wine were allowed, but not beer, which was believed to increase casual drinking.

With the rise of city break holidays abroad in the 1970s, interest in beer started to grow as people would visit pubs and bars on their travels. The general public was also frustrated that a legal exception was made for Icelandic airport workers, such as pilots and stewardesses, who could buy beer at the duty-free store and take it with them to their homes in Iceland. Finally, on March 1st, 1989, after a push from the public, beer was allowed in Iceland again. The date is known as Beer Day and is celebrated each year in Iceland by having a beer or two.

- Read more about Beer Day in Iceland

Brennivin

In 1935, the government of Iceland produced Brennivin, a clear, unsweetened akvavit schnapps flavored with caraway to celebrate the end of the prohibition. The bottle contained a black label to make it bland and unappealing to the public, which earned the product the nickname "Svarti Daudi" or "Black Death."

Eventually, an outline of Iceland was included on the black label and became one of the nation’s most recognized brands. The drink is considered Iceland's signature distilled beverage and is produced by the Egill Skallagrimsson Brewery today, which still uses the same old recipe and the trademark black label.

A handful of other companies make the drink, modernizing the recipe and infusing the caraway flavor with ingredients like angelica and dulse.

- Learn more: What is Brennivin and How Is It Made?

Icelandic Liquor

Many distilleries in the country produce schnapps, vodka, or gin inspired by what they find in Icelandic nature. Go to any cocktail bar in Reykjavik and get a cocktail with a liqueur made with ingredients such as birch, rhubarb, or crowberries. A good way to get to know Icelandic liquor is with this guided Reykjavik beer & schnapps walking tour.

When visiting Iceland, you should check out these items (just remember to drink responsibly):

-

Opal flavored vodka shots - this is licorice alcohol. This drink is based on the popular licorice lozenges. You can also get one called Topas, which is equally tasty.

-

Floki Whiskey - Icelandic whiskey made only from Icelandic ingredients (including home-grown barley). Try the 1-hour Eimverk distillery tour to see how it's made!

Icelandic Craft Beer

In recent years, craft beers have swept the nation. You can find high-quality Icelandic craft beers at the ATVR alcohol store and numerous bars around the country. You should try at least one of them.

There’s a great selection of local Icelandic beers to try and plenty of bars in Reykjavik to explore as well, allowing you to take in both the taste and the culture at the same time.

One of the most unique experiences you can do in Iceland is to visit the Kaldi brewery in North Iceland and bathe in beer at the Bjorbodin Beer Spa.

Modern-Day Icelandic Food

What do people eat in Iceland now? With modern technology, especially regarding food preservation, such as freezers and refrigerators, the diet of Icelanders has changed.

Traveling abroad brought all kinds of ideas that, combined with traditional ingredients, created some incredible flavors in modern Icelandic gastronomy. In Reykjavik, you’ll find many multicultural restaurants and a burgeoning local food scene. The emphasis is on purity, simplicity, and freshness.

Fine dining restaurants, gastropubs, brasseries, bistros, and burger joints are aplenty in Reykjavik, and vegan and vegetarian restaurants are rising. In recent years, many food halls have opened up around the city where people can dine together with food from multiple vendors in one place.

However, traveling outside the city, you’ll find more traditional restaurants serving mostly fish and lamb. But those who are picky eaters should always be able to find a pizzeria or a fast food joint.

So, if you plan to travel to Iceland, you don’t have to worry about eating sharks or ram testicles. You’ll have plenty of food to choose from, and you're sure to find something to your liking.

What are the Icelandic dishes you’d most like to try? Or, if you have already visited, what did you think of Icelandic food? What was your favorite? We’d love to hear from you in the comments below.

Altri articoli rilevanti

Location cinematografiche in Islanda: la lista completa

Quali film internazionali sono stati girati in Islanda? Perché i produttori di Hollywood scelgono di girare in Islanda? Scoprilo con il nostro elenco completo dei film internazionali girati nel pae...Leggi altro

Gli Yule Lads islandesi e Gryla | I troll di Natale in Islanda

Chi sono gli Yule Lads islandesi? Chi si festeggia in Islanda a Natale se non Babbo Natale? Che ruolo ha la gigantessa Gryla nel folklore natalizio islandese e chi è il gatto di Natale? Continua a l...Leggi altroNatale in Islanda | La guida completa alle tradizioni natalizie, al cibo e a tanto altro ancora!

Scopri tutto sul Natale in Islanda. Quali sono le principali tradizioni natalizie islandesi? Perché l'Islanda ha 13 Yule Lads e non Babbo Natale? Come si festeggia il Natale in Islanda? Com'è il Nat...Leggi altro

Scarica il più grande mercato di viaggi in Islanda sul telefono per gestire l'intero viaggio da un unico posto

Scansiona questo codice QR con la fotocamera del telefono e premi il link che compare per avere sempre in tasca il più grande mercato di viaggi in Islanda. Inserisci il numero di telefono o l'indirizzo e-mail per ricevere un SMS o un'e-mail con il link per il download.