A Complete History of Iceland

- How Old Is Iceland?

- The Settlement of Iceland

- When Was Iceland Discovered?

- Who Were the First Settlers in Iceland?

- Life in Early Iceland & the Adoption of Christianity

- Iceland’s Civil War: The Age of Sturlungs

- The Laki Eruption and the Mist Hardships

- Iceland in World War II

- Iceland Declares Independence

- Iceland History and Culture Today

Discover the complete history of Iceland in this detailed account. Learn who the first settlers of Iceland were, what life was like, and how it became the republic it is today. Are you wondering how the country's geography, climate, and position in the world affected its development, and what were some of the most positive and negative chapters in Iceland's history? We’ve got you covered!

Today, Icelanders stand at the precipice of a new, exciting and divisive chapter in their young country’s history. With millions of visitors discovering Iceland each year, an ongoing flow of immigration, and the urban development that goes with both trends, the Iceland of yesteryear is coming to a swift close, like it or not.

Already, the city of Reykjavik has taken on a new face. What once resembled an overgrown Scandinavian village has given way to the hurried construction of luxury hotels, visitor centers, and tourist stops. Only a few decades before that, it had become subject to the modernism that followed World War II—the theaters, the restaurants, the museums, and the bars.

- See also: International Relations of Iceland

- Find out everything you need to know about the History of Reykjavik

- Discover the Fascinating History of Icelandic Architecture

Such transformative makeovers have only occurred in the capital a handful of times, but today, the renaissance is evident.

Quintessential Icelandic streets such as Laekjargata and Laugavegur no longer resemble anything they once were. This is not a bad thing, only a visible reminder that nothing remains the same. Every day, it seems this city, country, and population are changing.

- See also: Maps of Iceland

What was it Dorothy said? “We’re Not in Kansas anymore.” The same could easily be applied to Iceland, a country that knows a thing or two about rapid growth.

Such development would seemingly imply that this once isolated, North Atlantic island now holds a prominent position in the psyche of international travelers. Holidaymakers, business people, artists, musicians, students, job-seekers—in recent decades, all types have found Iceland to be a land of plentiful opportunity. Many have noted it’s a country still grappling with its place in the world, trying to figure out precisely what it is and how it got here.

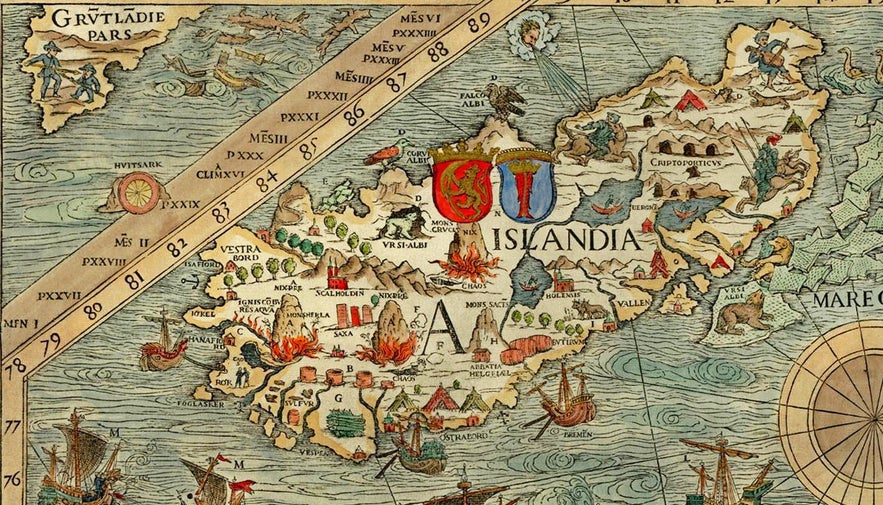

Photo by Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Olaus Magnus.

Photo by Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Olaus Magnus.

Tourism has been the saving grace of the Icelandic economy, which was in freefall during the 2008-2011 banking crisis. Having recovered financially and outmatched the GDP of previous years, Iceland’s future has never looked brighter.

- See also: Sustainable Tourism in Iceland

But how did Icelanders reach this unique and monumental moment in their national timeline? To face the challenges of the future, residents here will have to look back on this country’s fascinating history, from its early settlement to its declaration of independence after World War II, as well as the contentious and influencing years that followed.

How Old Is Iceland?

Iceland first began to form approximately 70 million years ago. A large magma pocket sits beneath the island and is thought to have been the catalyst that started this process.

This magma pocket is known as the Iceland Plume. Its origins are thought to lie over 6,500 feet (2,000 meters) inside the Earth’s mantle. Long before the dawn of humankind, this plume caused a series of underwater eruptions that quickly began to sculpt the island we know today.

These same forces can still be seen in volcanic eruptions or earthquakes. In the Vestmannaeyjar archipelago, the island of Surtsey was created from 1963 to 1967 due to underwater volcanic eruptions. Today, Surtsey is classified as a protected reserve, with only the academics studying it allowed to set foot on the island.

- See also: Top 5 Islands off Iceland

Iceland’s position in the middle of the Mid-Atlantic Rift makes it a hotbed for geothermal activity. It's still the primary reason Iceland boasts over 200 different volcanoes, geysers, and volcanic fissures. As you can see, Iceland’s volcano history goes way back.

Not only will visitors here have multiple opportunities to visit these, but they will also catch a rare glimpse of the exposed North American and Eurasian tectonic plates. These plates are moving apart every so slightly (0.04 inches or 1 millimeter a year) at Thingvellir National Park, the country’s only UNESCO World Heritage site.

- See also: National Parks in Iceland

And while it's simpler to consider these elemental forces as ancient Iceland history, something long forgotten, the truth is, Iceland is still very much experiencing growing pains.

Consider the ice-capped volcano, Eyjafjallajokull, which erupted in 2010 after a 200-year silence.

After centuries of building pressure, Eyjafjallajokull’s eruption would go on to shape Iceland’s future, causing an enormous ash cloud that halted air traffic over mainland Europe while simultaneously triggering the country’s burgeoning tourist industry. This is in itself a strange dichotomy considering the eruption also resulted in the cancellation of 107,000 flights.

Though less consequential, there have been countless other eruptions and earthquakes over the years. Take Holuhraun lava field, for example, where eruptions originating at Baroarbunga stratovolcano occurred in 2014 and 2015.

Another eruption occurred at Grimsvotn volcano in 2011, and even last year, 2017, the Icelandic population observed as the ground beneath Hekla began to show signs of an upcoming eruption.

The Settlement of Iceland

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Johan Peter Raadsig.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Johan Peter Raadsig.

What we know of Iceland’s earliest settlers can be traced back to the Landnamabok or the Book of Settlements. This five-part medieval manuscript tells the story of the Norsemen discovering and settling the country in the 9th and 10th centuries.

- See also: Vikings & Norse Gods in Iceland

Given its staggering age, the Landnamabok provides incredible detail regarding this period, presenting over 1,400 settlements and 3,000 characters, anecdotal tales, family trees, and stories of the Norse Pantheon.

The saga academic, Sigurour Nordal (Sept. 14, 1886 to Sept. 21, 1974) described this medieval literature as follows: “No Germanic people, in fact, no nation in Northern Europe, has a medieval literature which in originality and brilliance can be compared with the literature of the Icelanders from the first five centuries after the settlement period.”

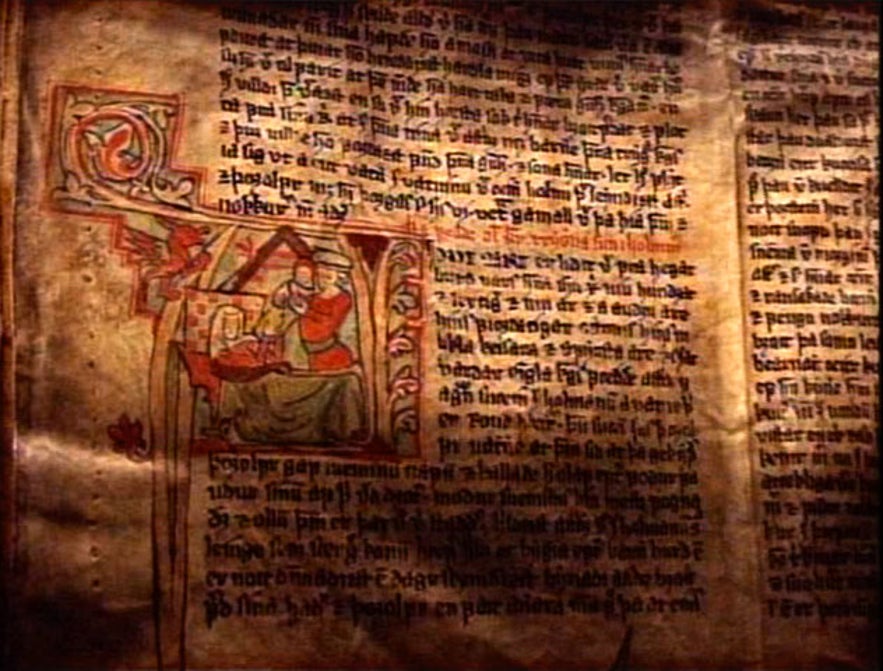

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by the Arni Magnusson Institute.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by the Arni Magnusson Institute.

Thankfully, the Icelandic language is largely unchanged from Old Norse, meaning they're just as accessible today to native speakers as they were nearly 1,000 years ago.

Contemporary Icelandic names are shared by Iceland’s first settlers, providing an intergenerational connection. Modern Icelanders know the sagas and their colorful characters like the back of their hand, having been taught them throughout their childhood.

When Was Iceland Discovered?

For a long time, Iceland was one of the largest uninhabited islands. Greek and Roman literature mentions the land of Thule, and some have speculated this may have referred to Iceland. However, this is merely a guess. This writing dates to around 330 B.C. and the Greek explorer Pytheas who documented his travels.

Archeological evidence suggests that early Irish monks discovered Iceland and settled here before the Norse arrived. The monk Dicuil wrote in the second half of the 8th century about clerics who had lived on the island.

Who Were the First Settlers in Iceland?

The Landnamabok refers to Irish monks, known as “the Papar,” as the first inhabitants of Iceland, having left behind books, crosses, and bells for the Norse to later discover. This is just one example of the level of detail found in these medieval sources.

- See also: Icelandic Literature for Beginners

They're also referred to in the Islendingabok (Book of the Icelanders) by Ari Thorgilsson as “wandering Christians” who departed the island because of their dislike for the “northern heathens.” Both examples seem to insinuate that the Papar had set up and abandoned residency before the official Settlement Age.

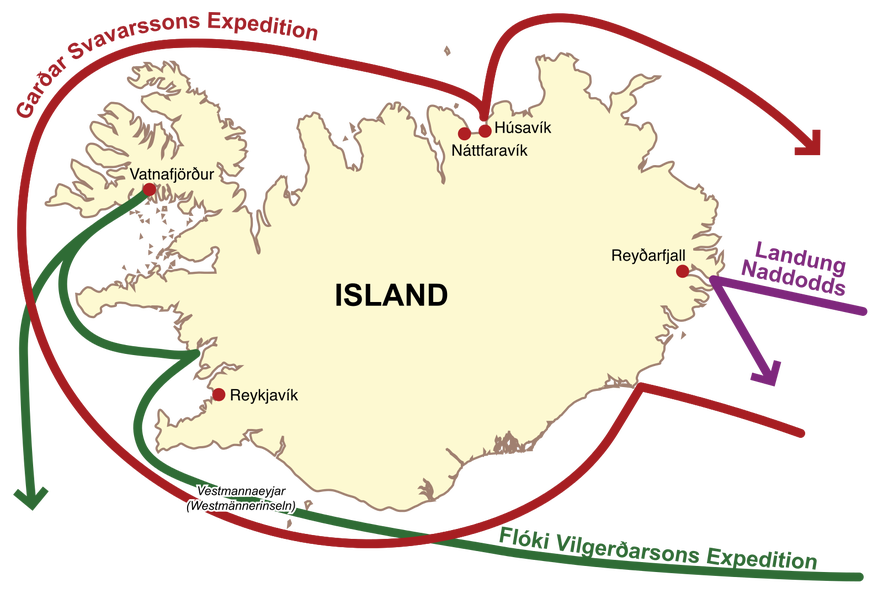

A Scandinavian sailor, Floki Vilgeroarson, gave Iceland its name after he spotted some drift ice in the fjords during a ferocious winter. Hrafna-Floki (Floki of the Ravens), as he is called, was the first Norseman to deliberately set sail to Iceland. His story is also told in the ancient Landnamabok.

Ingolfur Arnarson is credited as Iceland’s first permanent settler, though he also arrived at the island with his brother-in-law, Hjorleifr Hroomarsson. He was later killed by his slaves after settling at Mount Hjorleifshofoi, just east of modern-day Vik.

- See also: Witchcraft and Sorcery in Iceland

As legend has it, Ingolfur threw overboard two carved pillars and pledged to settle wherever they landed. In due time, the pillars were found in current-day Reykjavik, where he settled with his family in 874.

These were some of Iceland’s original inhabitants. Unlike many Nordic countries, there are no indigenous people of Iceland.

Norwegian chieftains followed Ingolfur en masse through the next few decades to escape the heavy-handed King Harald of Norway, and in about 60 years, Iceland was fully settled. By A.D. 930, it's thought that all arable land in the country had been settled.

Before the long period of growth, Iceland would soon experience, the settlement had grown so large that a new legislative body was in order; the ruling chiefs, therefore, established the Althingi, which is believed by many to be the world’s oldest nation-wide parliament.

Life in Early Iceland & the Adoption of Christianity

Around the time of the first settlers, it's suspected that approximately 40 percent of Iceland was covered with natural birch wood forests. This percentage was quickly depleted by the new arrivals, who were quick to use the material for constructing ships, homes, and farmsteads.

- See also: Folklore in Iceland

Trees that were not used for building were burnt for warmth. Within a century, it's thought that Iceland was entirely deforested. This would have consequences regarding soil arability that has lasted until today.

Until the 14th century, traditional Viking longhouses were built by the first inhabitants of Iceland. Due to a lack of timber, Icelanders held on to a tradition of building sod houses, otherwise referred to as an Icelandic turf house, a type of dwelling made by cutting two rectangles of sod, then piling them into the home’s interior walls.

This left enough room for windows and doors, but these homes were rarely warm and required great fires in the center of the room, which often caused respiratory problems. The roofing was often turf as the house was built into the hillsides, and they frequently had to be repaired due to rain damage.

To sustain life in Iceland, the early inhabitants needed to trade with the outside world. While Iceland was abundant with specific resources such as poultry, cattle, sheep, horses, pigs, and fish, the people still lacked many of life’s essentials and luxuries.

Trade was usually undertaken on short routes to neighboring Scandinavia and Europe as Iceland’s merchants were primarily farmers and thus could not afford to spend too much time away from their primary source of income.

- See also: Wildlife and Animals in Iceland

From Greenland, Icelanders would import walrus ivory, fur, and skins. They acquired such fine things as gems, silver, jewelry, and wine from Byzantium. England provided early Icelanders with wheat, tin, honey, and barley, while Russia and the East Baltic region offered up amber and slaves in equal measure.

For a time, Icelanders held onto beliefs in Norse mythology, following an oral tradition back to the time of their ancestors in Scandinavia. However, when Olaf Tryggvason ascended the Norwegian throne in A.D. 995, he decided to focus his efforts on converting those under his rule.

Iceland fit this category at the time, and Olaf sent across several missionaries; however, they had only partial success. In A.D. 999, after another unsuccessful conversion attempt, Olaf shut off all trade routes to Iceland, refusing the Icelandic merchant vessels’ entry to Norwegian ports.

To avoid a civil war in Iceland, the pagan lawspeaker Thorgeir Thorkelsson was elected to decide whether Iceland should become a Christian country. Thorgeir was chosen for his reputation as a reasonable man who could act as a peaceful mediator between both sides of the debate.

After deliberating for one day and one night under a fur blanket, Thorgeir finally concluded that Iceland should adopt a new faith. To mark the occasion, he brought his pagan idols to a waterfall and threw them in the abandonment of faith. This waterfall, Godafoss (“Waterfall of the Gods”), is a popular visitors’ attraction in Iceland today.

- See also: Waterfalls in Iceland

Thorgeir stipulated that pagan worship would still be allowed in private, as well as the “exposure of surplus children” (infanticide—Icelanders believed the island could only hold so many people) and the consumption of horseflesh. These directly went against the church’s teachings but were ingrained cultural habits in the Icelandic population. Once the church garnered complete control in Iceland, these practices were quickly banned.

Iceland’s Civil War: The Age of Sturlungs

In the 13th century, a civil war known as the Age of the Sturlungs gripped Iceland. In 1220, this conflict saw powerful Icelandic chieftains (Gooar) battle to decide whether Iceland should become a subject of Hakon the Old, King of Norway. This period of conflict is named after the Sturlungs, a powerful family in Iceland at that time.

Snorri Sturluson was the chieftain of the Sturlung clan and a vassal of the Norwegian king, as was Snorri’s nephew, Sturla Sighvatsson. While his uncle is more famed as a saga writer, Sturla would make a name for himself, aggressively warring with rival clans who refused to accept they were subject to the Norwegian monarch. This culminated in the Battle of Orlygsstaoir—the largest known battle in Icelandic history—where Sturla was soundly defeated.

However, skirmishes continued to erupt in the following years, and the Norwegian king was nothing if not persistent in stirring up trouble. Gissur Thorvaldsson, himself a chieftain and one of the former opponents of Sturla, was made a chief by the Norwegian king. Gissur did much to push the King’s efforts, and finally, in 1262, the Gamli Sattmali or Old Covenant was signed.

This agreement ended the Icelandic Commonwealth, and the island became a vassal of the Kingdom of Norway.

One century later, Iceland would be granted to the Danish. Denmark’s Christian III challenged the open religious practices of Icelanders and imposed Lutheranism on the people, and to this day, most religious Icelanders remain Lutheran.

The Laki Eruption and the Mist Hardships

Disaster struck Iceland with the violent eruption of the Laki volcano in the 18th century, beginning June 1783 and ending Feb. 1784, killing 9,000 Icelandic citizens. This eruption was known as Skaftareldar (Skafta fires). The lava wiped out almost all of the nation’s livestock, estimated at 80 percent, bringing a famine that killed up to a quarter of Iceland’s population.

- See also: Volcanoes in Iceland

“This past week, and the two prior to it, more poison fell from the sky than words can describe: ash, volcanic hairs, rain full of sulfur and saltpeter, all of it mixed with sand.

The snouts, nostrils, and feet of livestock grazing or walking on the grass turned bright yellow and raw. All water went tepid and light blue in color, and gravel slides turned grey. All the earth's plants burned, withered and turned grey, one after another, as the fire increased and neared the settlements."

This period of starvation, one of the worst the civilized world has ever experienced, is known as the Mist Hardships in English or Moouharoindin in Icelandic. As hunger set in and the weather patterns began to take a life of their own, social order in Iceland broke down, and looting became frequent.

- See also: Things That Can Kill You in Iceland

Aside from the prevailing hunger, many would die from extreme heat or the toxic gas that filled the air.

British cleric, Gilbert White, wrote of the period:

“All the time, the heat was so intense that butchers’ meat could hardly be eaten on the day after it was killed, and the flies swarmed so in the lanes and hedges that they rendered the horses half frantic, and riding irksome. The country people began to look with a superstitious awe, at the red, louring aspect of the sun."

The eruption had widespread consequences outside of Iceland; its influence reached such far-flung corners as North America, the Sahel of Africa, and Europe. Disrupting the monsoon cycles of Africa and India, the eruption caused widespread famine in Egypt (resulting in a loss of ⅛ of the population). The subsequent poverty and food shortages in France contributed to the French Revolution.

Iceland in World War II

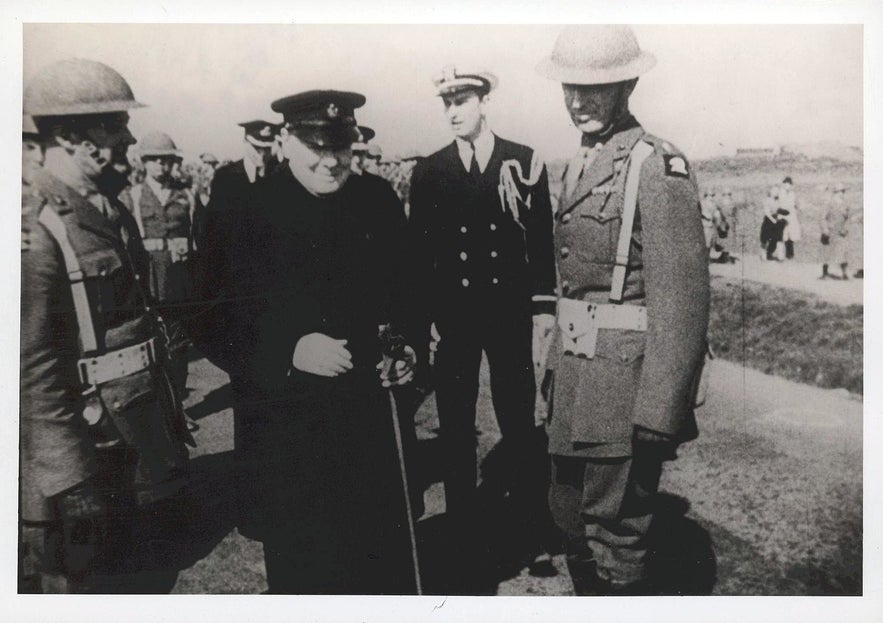

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by army.mil.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by army.mil.

The recent history of Iceland picks up in the middle of the 20th century. Iceland finally became a republic on June 17, 1944, when 97 percent of voting Icelanders opted in favor of independence from Denmark.

This vote occurred only four years after Denmark had succumbed to the invading German army. This position had left Iceland, a neutral country, in a rather precarious position. But was Iceland ever at threat from the Axis powers in the first place?

It should be understood that Iceland’s position on the globe is one of enormous strategic importance for any party engaged in international warfare. Iceland is positioned directly between mainland Europe, to its east, and North America, to its west, and looms over the Atlantic Ocean.

This is a highly advantageous spot for tacticians who understand that whoever operates military bases in Iceland, be they ports or airfields, has dominion over sea and air traffic in that vast and vulnerable stretch of ocean, as well as easy access to both landmasses.

In the early 1930s, however, the Third Reich had shown little interest in taking Iceland, though Allied forces found that this position quickly changed after the onset of war, especially following Operation Weserübung, the Axis invasion of Norway, and Denmark.

- See also: Top 9 Museums in Reykjavik

Britain, in particular, felt that this threatened their control of the North Atlantic and quickly telegraphed the Icelandic capital, asking them for their support as “a belligerent and ally.” So too did Britain want to build bases in Iceland to strengthen their North Patrol. Reykjavik responded by confirming their neutrality.

The next day, April 10, the Icelandic Parliament declared that Denmark could not fulfill its duties supporting Iceland and thus transferred all powers to the domestic government. Two days after, Operation Valentine saw the British invade the neighboring Faroe Islands. It was a sure sign of the events to come.

On May 6, British prime minister Winston Churchill made a case to the war cabinet that building military bases in Iceland was essential in preemptively denying the country to Axis forces. He argued that further diplomatic efforts with the Icelandic government would likely reveal British invasion plans to the Germans; hence it was a more strategic move to invade without any prior warning.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by USMC Archives.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by USMC Archives.

There was little fear such an operation could fail. After all, the Icelanders had no standing army, and there would likely be only a handful of German resistors. On May 3, the British Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs, Alexander Cadogan, wrote in his diary, “Home 8. Dined and worked. Planning conquest of Iceland for next week. Shall probably be too late! Saw several broods of ducklings.”

The invasion plan known as Operation Fork was conducted haphazardly en route. There were no Icelandic speakers among the invasion force, and many of the maps being used had been drawn from memory.

Luckily for both parties, Icelanders spotted a British reconnaissance plane surveying Reykjavik, giving them advanced notice that the British would arrive immediately. When the force finally did come, the British were surprised to find the Icelanders rather accommodating, even helping the soldiers unload supplies from their ship.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by the Royal Navy.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by the Royal Navy.

Upon arriving at the German consulate, British forces were relieved to find no resistance. What they did find, however, was a fiery bathtub, midway through burning intelligence documents, and Consul Gerlach angrily protesting that Iceland was a neutral country.

After being reminded that Denmark had also been a neutral country, the Consul was arrested. Sixty-two unarmed German sailors were also arrested after being rescued from the Bahia Blanca, a German freighter that had recently struck an iceberg in the Denmark Strait.

During the war, the British and Canadian troops in Iceland would eventually fall to the wayside in favor of U.S. Forces. The British had called upon the then neutral United States to take over control of Iceland as their forces were badly needed on other fronts.

A great deal of development was undertaken throughout this period, namely Keflavik International Airport, Reykjavik Domestic Airport, harbors, hospitals, and road networks. Despite the incredibly beneficial economic impact, this action proved to be highly controversial to much of the Icelandic population, who continued to protest their neutrality, all the while cooperating with Allied troops.

- See also: The Nature of Icelanders

Equally controversial was the impact that foreign troops had on Icelandic society. During the heightened years of the war, foreign troops made up 50 percent of the native male population in Iceland, and local men were quick to notice the infatuation many Icelandic women showed toward these new arrivals.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by United State Army.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by United State Army.

This became known as astandio, or “Te Situation,” where women found to be engaging sexually with foreign troops were accused of prostitution and treasonous activity.

In 1941, it was thought the Icelandic police force was tracking over 500 women, many of whom were sent to institutions such as that at Kleppjarnsreykir in West Iceland, where they faced inhumane conditions and solitary confinement. Children fathered by foreign troops were known as astandsborn (children of the situation).

Iceland Declares Independence

The Icelandic constitutional referendum was held in 1944 as the closing chapters of the war began to materialize. Given that Nazi Germany still occupied Denmark in 1944, many Danes felt it inappropriate to hold such an election. The move was congratulated by King Christian X of Denmark after the Icelandic population voted 98 percent in favor of independence.

- See also: The Icelandic Flag | A Tale of Identity

According to stipulations in the 1918 Danish–Icelandic Act of Union, the two countries would maintain strong ties, with Iceland still falling under the territorial dominion of the Danish Monarchy. This subjection to the monarchy was later abolished in the same year, and complete autonomy was granted, with Sveinn Bjornsson serving as the first President of the Republic of Iceland.

Gaining independence meant that Iceland had to reinvent its position on the world stage as culturally separate from the Danish and its relationship with the rest of mainland Europe.

For example, the Icelandic flag was ratified by law in 1944. The inherent values of the Icelandic national psyche, such as religious expression, the preservation of their language—were collectively agreed upon as the founding principles of Iceland as an independent nation.

In the years preceding and immediately after independence, a wave of Icelandic nationalism had begun to find its footing in the Icelandic psyche, a cultural invention rooted mainly in the sagas.

They’re neither myth, nor epic, nor romances or folktales, but stories of vengeance, wealth, power, and love.

Jon Sigurosson bravely led a group of Icelandic intellectuals towards an independence movement, recreating an autonomous Icelandic government. He is credited as the modern-day founder of Iceland and is often referred to as President Jon by Icelanders, even though he was never officially the president of Iceland.

Iceland History and Culture Today

Despite their national independence, the Americans maintained a presence in Iceland long after the promised date of departure stipulated in the Keflavik Agreement. According to this contract, the Americans would leave Iceland following the end of World War II, transferring control of Keflavik Airport in the process.

However, given the alarming rate that anti-Communist rhetoric entered the mainstream political consensus in the United States, it was unilaterally decided that their presence should be maintained to deter Russian nuclear attacks.

This caused widespread protests in Iceland, to little avail, but did cement in the Icelandic psyche a distrust of widespread foreign intervention and the willingness to protest policies they considered opposed to the country’s value systems.

The airport was eventually returned to the Iceland Defense Force in 1951, though the U.S. Navy maintained Keflavik Naval Air Station until 2006. As of 2017, it's again the intention of the U.S. military to build a modern airbase on the Reykjanes Peninsula. According to the 1951 NATO Defense Treaty, the United States is responsible for defending Iceland for an undisclosed length of time.

This should come as little surprise; after all, Icelandic society might be moving rapidly, but the country’s strategic positioning above the Atlantic is as important today as it ever has been. So too is the American influence that still lingers in Iceland—even now, it's clear that this is a country of hot dog lovers, cinephiles, rock n’ roll musicians, and revolutionaries.

For the latter half of the 20th century, unemployment was low, industries were prospering, and life in Iceland was good, particularly for the most part, save for years when the annual harvest proved insufficient. In 1949, Iceland joined as one of the founding members of NATO, while only a year before, the country had begun to receive Marshall Aid from the United States.

The next decade of significant interest in Iceland is the 1980s. In 1986, Iceland hosted the Reykjavik Summit, a meeting between U.S. President Ronald Reagan and General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev, regarding nuclear disarmament.

This ultimately unsuccessful meeting of minds—the issues would, thankfully be resolved in the next year—took place at Hofoi House, marking a new era. In 1989, Vigdis Finnbogadottir became the President of Iceland and the world’s first democratically elected female head of state.

In the 1990s, the Independence Party set a drastic reform of Iceland’s economy into motion. As with most significant changes, it took some time to acclimate, but the economy began to grow again strongly and swiftly after a brief recession.

Growing at a rate of 4 percent per year on average, the Icelandic economy diversified its industries not to be overly reliant on fishing. Iceland joined the European Economic Area in 1994, thus strengthening its position on the international financier’s stage.

- See also: The Ultimate Guide to Downtown Reykjavik

For a short time, Icelanders considered banking their new modus operandi. In the wake of the 2008-2011 credit crunch, this proved to be a short-lived, reckless dream. They would have to look elsewhere if they were ever going to recoup the losses accumulated over the years of the financial crash.

As luck would have it, the world’s eyes were already on Iceland, particularly the dark and spewing ash cloud permeating from it. The eruption of the Eyjafjallajokull volcano was worldwide news and affected much of Europe. It was then that various agencies in Iceland, including the government and tourist board, rallied around the concept of boosting the country as a must-see travel destination.

Iceland has also been utilizing its resources for green energy production and has built numerous geothermal power plants and dams for hydroelectric power stations. This has had both incredible benefits and detriments to the Icelandic community, sparking an ever-hot debate on the preservation of nature versus the utilization of energy sources.

- See also: Iceland's Troubled Environment

The history of Iceland is rich with legend and lore, ranging from the first settlement that was established here over a thousand years ago to the prosperous, liberal, and modern Scandinavian nation that it is today. Thanks to a healthy economy and the island’s natural resources, Icelanders are looking forward to a bright and beautiful 21st century.

Did you enjoy our article on the history of Iceland? Did you learn anything new? Was there a particular chapter in history you'd like to know more about? Feel free to leave your thoughts and queries in the Facebook comments box below.

Otros artículos interesantes

Yule Lads Islandeses y Gryla | Trolls de Navidad en Islandia

¿Quiénes son los Yule Lads islandeses? Si no es Papá Noel, ¿a quién entonces se celebra en Navidad? ¿Qué papel tiene la gigantesca Gryla en el folclore islandés en Navidad? ¿Y qué es el Gato de Navi...Leer másNavidad en Islandia | Guía Definitiva de Tradiciones, Comidas Navideñas y Más

Entérate de todo lo que pasa en Islandia en Navidad. ¿Cuáles son las principales tradiciones navideñas en Islandia? ¿Por qué Islandia tiene 13 Yule Lads? ¿Es lo mismo que Papá Noel? ¿Cómo se celebra...Leer másLocalizaciones de películas en Islandia

¿Qué películas y series de televisión internacionales han sido filmadas en Islandia? ¿Por qué eligen los productores Islandia para rodar? Consulta esta lista de personajes famosos de Islandia A...Leer más

Descarga la mayor plataforma de viajes a Islandia en tu móvil para gestionar tu viaje al completo desde un solo sitio

Escanea este código QR con la cámara de tu móvil y pulsa en el enlace que aparece para añadir la mayor plataforma de viajes a Islandia a tu bolsillo. Indica tu número de teléfono o dirección de correo electrónico para recibir un SMS o correo electrónico con el enlace de descarga.