10 Questions about Icelandic Names Answered

- Where do Icelandic names come from?

- How Do Icelandic Last Names Work?

- Do All Icelandic Names Mean Something?

- What Are The Most Common Names In Iceland?

- Do Icelanders Have Middle Names?

- Are There Rules About Icelandic Names?

- What Letters Can Icelandic Names Start With?

- Do Immigrants In Iceland Have To Change Their Name?

- Are There Any Gender-Neutral Names In Iceland?

- What Would My Name Be If I Was Icelandic?

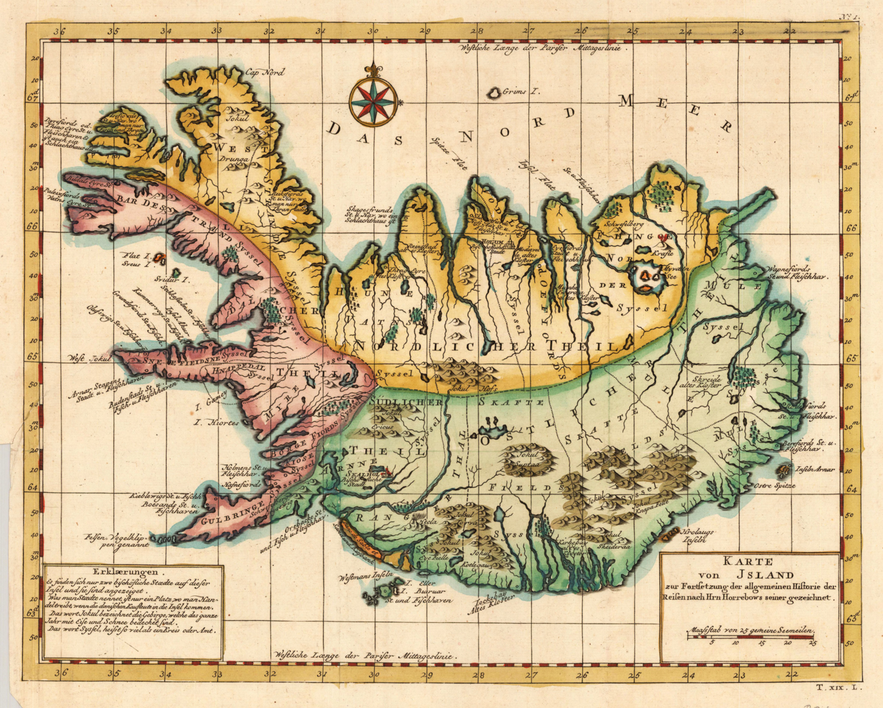

Icelandic names have left many a foreigner puzzled and tongue-tied. On the volcanic island in the North Atlantic lives a nation of a little over 350.000 people with its own language and a unique alphabet. Jón Jónson and Björk Guðmundsdóttir might seem like a random jumble of letters but in Iceland, they are as mundane as boiling hot water shooting out of the earth.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by GDK. No edits made.

- Learn about the History of Iceland before you visit

- Book a Culture Tour in Iceland to learn more about the Icelandic culture

- Decide What to Do and Where to Go in Iceland

- Find out about the Weather in Iceland

Naming traditions in Iceland are fascinating and might seem complicated to the outside eye. Icelandic people often get questions from foreigners about their names. The following are answers to some of the most common questions about Icelandic names. Hopefully, it’ll give you a good overview of how Icelandic people choose names for their children.

Where do Icelandic names come from?

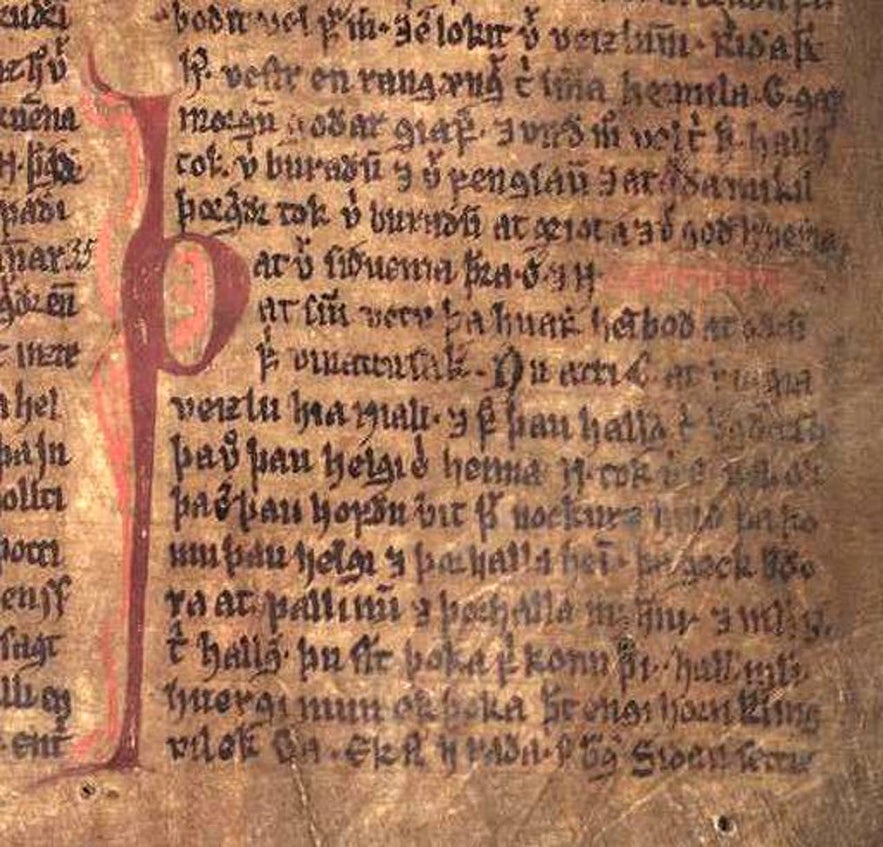

The earliest records of residents in Iceland are the tales of the first settlers and the Sagas. These documents from the 9th and 10th centuries might not be the soundest historical evidence but they give us an idea of where Icelandic names come from. Many of those names are still used today. For example, Ingólfur Arnarson – credited as the first settler – bore a name that is still given to Icelandic boys today.

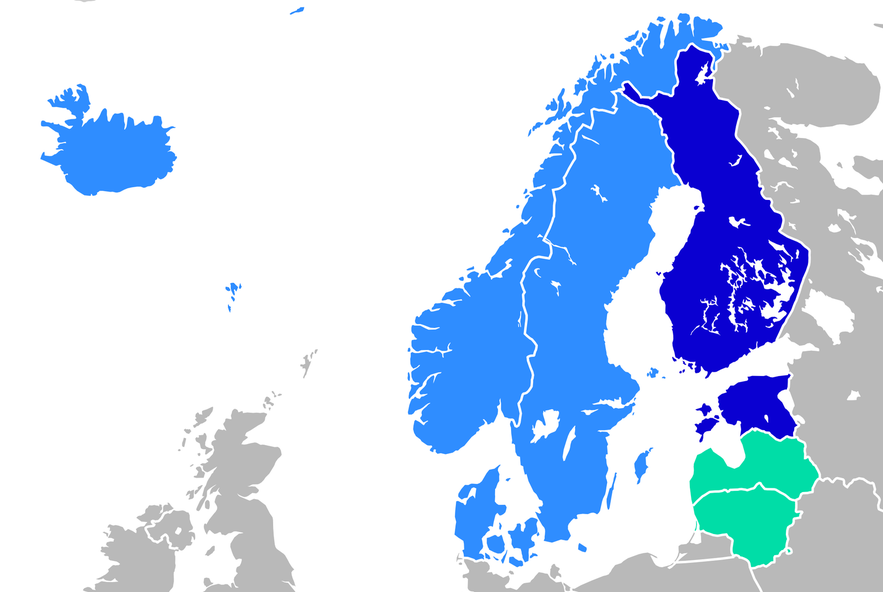

Most Icelandic names originate from other countries. The majority of the first settlers came from Norway and brought with them their naming traditions. Some also came from the eastern-Nordic countries, Sweden and Denmark, and those names were added to the mix.

See also: Where Did Icelanders Come From?

Of course, all of the Scandinavian countries have similar names given their shared Germanic linguistic heritage. This means many of the names also exist in languages like English and German, although often with slightly different spellings. The first Icelandic settlers also brought with them Irish slaves, who in turn, brought Celtic names to Iceland.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Christian Krohg. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Christian Krohg. No edits made.

The only names that can be considered uniquely Icelandic are those made-up in more recent years. These are often names put together from other already existing names. However, some new names have been made by using words from Icelandic vocabulary, for example Stormur (Translation: Storm) and Vísa (Translation: Verse/Poem).

Many Icelandic names are taken from Norse Mythology. When it was still the predominant religion, people would use the deities’ names at the start or end of existing names as a prefix or suffix. The most common being the name of the thunder-god Þór (Thor).

Since worship of the Norse gods became less common, people have started giving children the names of the gods. Names like Þór, Freyja, Sif, Óðinn and Loki are still common today.

See also: Vikings and Norse Gods in Iceland

In the year 1000 Christianity became the national religion in Iceland by law. The new religion brought with it a whole host of new names. It became common for people to name their children names with the prefix Krist-, the Icelandic version of the Christ- prefix used in English. Names like Christian and Christina acquired Icelandic counterparts; Kristján and Kristín.

How Do Icelandic Last Names Work?

The more common type of Icelandic last-name is the patronymic or sometimes matronomyc name. This means a last name originating from a father’s or mother’s given name.

It’s more common to identify a child by its father, which makes it a patrilineal naming tradition… just like most other naming traditions.

How these traditional Icelandic last names work is simple: they are made up of the first name of a person’s parent – more commonly their father, patriarchal – and the suffix -son or -dóttir (English: son or daughter).

For example, a male whose father’s name is Jón will have the last name Jónsson and if he has a sister her last name will be Jónsdóttir. Unless they choose to be known by the name of their mother, foster-father or step-father. Some choose to be known by both their mother and father’s name.

The less common is a family name. These work the same as surnames used in English-speaking countries. These names can only be inherited, you can not make up a new family name. Icelandic citizens who marry a person with a family name are not allowed to take their spouse’s last name. They can however make the spouse’s last name their middle-name.

Some of these family names were established in the country when foreign merchants settled here. Many of those names were Danish. Other family names were made up by Icelanders who studied abroad and wanted to seem cosmopolitan, though this is no longer possible since laws prohibit people to take up non-existing last names. Purely Icelandic family names are usually taken from the names of geographical locations like farms, towns and fjords.

Do All Icelandic Names Mean Something?

A lot of Icelandic names have a meaning that is easy to understand if you speak the language. Others are more difficult unless you have a very old-fashioned vocabulary. But all Icelandic names do have some sort of meaning.

It’s common for Icelandic names to be based on things from nature, including animals. You could even name your son Worm or the plural Worms; Ormur and Ormar. Bird names are very common. Lóa (Golden Plover), Svala (Swallow), Ugla (Owl), Þröstur (Robin), Örn (Eagle), Haukur (Hawk), to name but a few of the beautiful bird names available.

See also: Wildlife and Animals in Iceland

Some land mammals also get human namesakes. The most popular are probably names relating to bears. This might seem strange since Iceland has no indigenous bears, and Polar Bears only find their way here on rare occasion from neighbouring Greenland. The name Björn was brought here by Norwegians and remains popular to this day; other names taken from the word bear include Bjarni, Birnir and Birna.

It’s interesting that a nation which has had to rely heavily on fishing to sustain themselves doesn’t look to fish for inspiration when naming their children. The most common name a human can share with a sea-creature is the female name Hrefna (Minke Whale).

See also: Whale Watching in Iceland

There are some male names—Karfi (Rockfish), Hængur (Male trout or salmon)—but Karfi hasn’t been used for decades and only 3 people currently have the name Hængur. Fish names might be something for future parents to consider if they want to name their child something unique.

Many names are synonymous with plants. Tree names include Ösp (Aspen), Eik (Oak) and Reynir (Rowan). A lot of common names are derived from the name of birch trees; Birkir, Bjarki and Björk, all birches. Much like in English, Icelanders can name their daughters after violets or buttercups; Fjóla or Sóley. Fewer male names are based on flowers, but some more ‘masculine’ plants are used, for example Burkni, which means Fern.

See also: The Björk Saga

Flora and fauna aren’t the only things from nature represented in Icelandic names. Inorganic natural phenomena are also found in Icelandic names. For example men can be named both ‘Rock’ and ‘Glacier’; Steinn and Jökull. Women can be named Sól or Sunna, which both mean ‘sun’ and men can be named Máni, which means ‘moon’.

Hrönn, Bára and Bylgja all mean ‘wave’ and were also the names of three of Ægir’s daughters from Norse Mythology. Ægir was the god of the sea and his name is also still used today. There are many other ocean related names. Ægir and Rán are both names which mean sea. Names with the prefixes Sæ- and Haf- are also common and those both mean sea or ocean. Examples of these names are: Hafsteinn (Sea-rock) and Særún (The rune of the sea).

See also: A Guide to Icelandic Runes

Icelanders have a lot of words to describe snow (at least 50, probably more) and some of those can also be names of people, more commonly women. Drífa, Fönn and Mjöll are all women’s names and words for snow. Fannar and Snær are male names made from snowy words.

Icelanders can also be named after things. Bolli is a funny example, it means cup or mug, understandably it’s not very popular. Other Icelanders bear names that are synonymous with concepts, like Eternal (Eilífur/Eilíf) or Peace (Friður). Men can be named Man (Karl) or Boy (Sveinn/Drengur) but Woman and Girl are not used as names.

What Are The Most Common Names In Iceland?

According to Statistics Iceland, the three most common names for females in 2017 were Guðrún, Anna and Kristín. For males the top three names are: Jón, Sigurður and Guðmundur.

6216 people in Iceland are named Guðrún, making it the most popular name of all. The name is female and means the letter of god. 6194 people in Iceland are named Jón. The name is taken from the Biblical name Jóhannes and is the Icelandic version of John.

Because of this, it’s very likely that the most common full name in Iceland is Guðrún Jónsdóttir. Since some Icelanders are named after their fathers, there are also a lot of Jón Jónson’s in the country but they often have second given names, for clarification. For example the singer Jón Jónsson, pictured above, whose middle name is Ragnar.

Do Icelanders Have Middle Names?

If a person is given more than one name from the list of approved first names those are not considered middle names, they are additional given names. Middle names exist in Icelandic but aren’t very common. These usually follow families or indicate where a person is from. There is a special registry for approved middle names. Some common Icelandic middle names are: Arnfjörð, Bjarndal, Fossberg, Hlíðkvist, Laufland, Seljan and Vídalín.

An Icelandic person can have up to three names in addition to their last name but only one of those can be a middle-name. Naming your child more than one name is fairly common practice in Iceland today but it’s a relatively new tradition. Very few people named in the Sagas have more than one given name.

See also: The Most Infamous Icelanders of History

The custom of giving children two names arrived in Iceland from Denmark in the 18th century. In the registry of 1801, there are 51 people with two given names. 44 years later the number of people with more than one name has risen to 1088. This trend really took flight in the 20th century, in 1910 a fifth of male Icelanders and a quarter of female Icelanders had more than one name. Of the newborns registered with Statistics Iceland in 2007 over 80% were given more than one name.

Unlike some countries where middle names are barely ever used except on birth certificates, Icelanders usually call each other by all the names they have. Additional names are used to differentiate between people who have the same name. To avoid all these names becoming too long, Icelanders use nicknames. A woman named Anna Sigríður, will probably be known by friends and family as Anna Sigga. A man named Ólafur Páll will likely be nicknamed Óli Palli.

Are There Rules About Icelandic Names?

There are lots of rules about Icelandic names, in fact there are not only rules but laws! The purpose of the laws is to maintaining the Icelandic language and protecting children. All allowed names are available in an online database.

There is a committee called Mannanafnanefnd (Translation: The Person Name Committee) that decides which names are allowed and which are not. This committee has existed since 1991 and is made up of three people who sit on the committee for a four year term.

The committee members are each nominated by one of the following: University of Iceland’s Department of Philosophy, University of Iceland’s Law Department and The Icelandic Language Council.

To be approved, names must be Icelandic or have become traditional in Iceland. They have to fit Icelandic grammatical structures and be written with the Icelandic alphabet unless other versions can be proven to be a tradition.

A name can be considered a tradition if: At least 15 people have the name. 10-14 people have the name and at least one of those people is over 30-years-old. 5-9 people have it and at least one of those people are over 60-years-old. 1-4 people currently have the name and it can be found in the name registry from 1910 or 1920. It can be found in at least 2 name registries before 1920.

A name can also be considered traditional through cultural significance, due to appearing in a treasured work of fiction, Icelandic or translated. Examples of first names that have been denied by the committee are: Berry, Indra, Theadór and Örn as a female name.

Guardians are not allowed to name a child something that could cause them discomfort, for example the name Satan is not allowed. The name must be of the gender that the child is assigned at birth. If the child has a foreign parent it can have one name which does not fit Icelandic naming traditions.

You have to name your baby before it turns six months old, either by baptism or by telling Þjóðskrá, otherwise known as Registers Iceland. The guardians will be notified and given a month’s extension to provide a name for the child, the guardians will be fined after that time.

Some people are against the committee and claim its existence to be a violation of people’s rights. Members of Parliament have repeatedly proposed bills which would have abolished the committee, but it has so far survived.

The band Memfismafían even wrote a satirical song about the committee (See above). The song features comedian and former Mayor of Reykjavík, Jón Gnarr, who in the past has quarrelled with the committee. For years the committee banned Jón from making his middle name, Gnarr, his legal last name.

What Letters Can Icelandic Names Start With?

The Icelandic alphabet has 32 letters:

A Á B D Ð E É F G H I Í J K L M N O Ó P R S T U Ú V Y Ý X Þ Æ Ö

There are three letters of that alphabet which no Icelandic name starts with, they are: É, Ð and X. In fact no words in the whole language begin with the letters X and Ð. If a word sounds like it starts with Ð (has a th-sound at the beginning) what you’re hearing is the letter Þ.

There are some letters which aren’t included in the Icelandic alphabet but still have approved Icelandic names which start with them. This is due to the rule about names which can be considered traditional despite not fitting Icelandic grammar. Letters which aren’t in the Icelandic alphabet but have approved names are: C, W and Z.

The letter Z was removed from the Icelandic alphabet in 1974 but some people who learned to read and write before that time still use it. There aren’t many Icelander whose name begins with Z, the most popular of the names is Zophonías, about 20 men bear the name.

There are considerably more names beginning with the letter C, among the most common are: Carl, Christian, Camilla and Charlotte. No female names in Iceland begin with W but 7 male names exist, the most popular being: William, Wilhelm and Walter.

Do Immigrants In Iceland Have To Change Their Name?

Until the law was changed in 1996, those seeking citizenship in Iceland whose names did not fit with Icelandic grammatical rules had to choose new names. This is no longer the case and those who were forced to change their names prior to 1996 are allowed to revert back to their original name. If new citizens so choose they can change their names to conform to Icelandic tradition, it is, however, no longer a legal requirement.

See also: How Hard is it to Speak Icelandic?

If an Icelander marries a person with a foreign last name they are not allowed to take their spouse’s last name. They are however allowed to use their partner’s last name as a middle name. Foreign citizens who marry Icelanders are allowed to take Icelandic middle names or use their spouse’s parental name.

Are There Any Gender-Neutral Names In Iceland?

The Icelandic naming system is very gendered. It’s rare for Icelandic names to be acceptable both as a male and a female name. As far as we can tell, there are only eight such names in the registry of Icelandic names, they are: Abel, Aríel, Auður, Blær, Eir, Elía, Júlí and Maríon. It’s difficult to get these names approved because approval is attached to whether they fit with how Icelandic words conjugate and whether words are masculine or feminine factors into the conjugation.

See also: Gender Equality in Iceland

In 2013 a 15-year-old girl named Blær had to sue the Mannanafnanefnd Committee because they refused to register her under the name Blær. The word blær is masculine and means breeze.

The committee’s reasoning was that Blær was traditionally a name given to those who are assigned male at birth. The girl – who at 15 was still registered as Stúlka (Girl) according to Registers Iceland – made her case based on the fact that a woman had previously been registered under the name Blær before the committee was established.

A female character by the name appears in Nobel Laureate Halldór Laxness’ 1957 book Brekkukotsannáll (English Title: The Fish Can Sing). This was where Blær’s mother got the name from and provides a cultural significance to the name being female. Blær won the case and is now registered under that name.

What Would My Name Be If I Was Icelandic?

If you became an Icelandic citizen you would be allowed to keep your own name, but just for fun lets build your own Icelandic name!

First thing’s first, get rid of any C, Q, W or Z. If your name is John or James it is now Jón or Jóhann. If your name is Mary or Marie it is now María. Exchange any Christ- suffixes with Krist-.

You can find an Icelandic version of your name or choose a completely new one from the official name registry Mannanafnaskrá. You could also choose your favourite bird, use an online translation engine to convert it into Icelandic and check the registry to see if it exists as an Icelandic name.

Choose up to three names, but remember that only one of them can be from the millinöfn (middle names) category. Also remember that people with two given names are often known by both names.

Next, what’s your parent’s first name? Use either your father or your mother’s name! Remember to get rid of the no-no letters, Z Q W C, from their name. Then stick the suffix -son or -dóttir at the back depending on your preferred gender; son for sons, dóttir for daughters. Now you have an Icelandic name!

Weitere interessante Artikel

7 Dinge, die Isländer am Tourismus in Island nicht ausstehen können

Finde heraus, was die Isländer an Touristen überhaupt nicht mögen und warum sie trotzdem so freundlich zu Besuchern sind. Erfahre, was du während deines Island-Aufenthaltes tun und was du lassen sol...Weiterlesen24 Dinge, die man in Island nicht tun sollte

Lies, was du in Island nicht tun solltest, damit du eine sichere und angenehme Reise genießen kannst. Was sind die dümmsten, ignorantesten oder einfach nur dämlichen Dinge, die Besucher in Island ge...WeiterlesenIsländisches Alphabet und Grundlagen der Sprache

Ist die isländische Sprache schwierig? Wie spricht man Reykjavik oder – besser noch – Eyjafjallajökull aus? Wie liest man das isländische Alphabet? Gibt es Ähnlichkeiten zwischen dem Deutschen un...Weiterlesen

Lade Islands größten Reisemarktplatz auf dein Handy herunter, um deine gesamte Reise an einem Ort zu verwalten

Scanne diesen QR-Code mit der Kamera deines Handys und klicke auf den angezeigten Link, um Islands größten Reisemarktplatz in deine Tasche zu laden. Füge deine Telefonnummer oder E-Mail-Adresse hinzu, um eine SMS oder E-Mail mit dem Download-Link zu erhalten.