Learn about the origin of the ancient Icelandic runes alphabet in this detailed guide. Discover the purpose of Icelandic staves such as Aegishjalmur and Vegvisir. Read on and learn all about these Icelandic Viking symbols and their meanings, mythological foundations, and magical abilities.

Runes are the characters that make up the ancient writing systems, known as runic alphabets, of various Germanic languages. Before the Latin alphabet, different types of runes were the main way of writing in Europe, including in the Nordic countries.

Why You Can Trust Our Content

Guide to Iceland is the most trusted travel platform in Iceland, helping millions of visitors each year. All our content is written and reviewed by local experts who are deeply familiar with Iceland. You can count on us for accurate, up-to-date, and trustworthy travel advice.

Today, travelers interested in Viking history and local traditions can discover ancient carvings and artifacts on some of the best culture tours in Iceland. These experiences can easily be added to vacation packages in Iceland, or you can rent a car in Iceland to explore historical sites at your own pace.

The exact origins of runes are debated, but runic archaeological findings date back as far as A.D. 150. Runologists believe the system originated from earlier Old Italic epigraphs, such as Old Latin or the Raetic alphabet of Bolzano.

As Christianity spread across Europe, the Latin alphabet gradually replaced runes. This change began around A.D. 700 in Central Europe, but in the Nordic countries, runes remained common until at least A.D. 1100, and even longer for special uses. Runes are a key part of Nordic heritage and culture.

Iceland’s early settlers brought runic writing with them, and it has stayed alive in various forms ever since. More than just a writing system, runes are deeply tied to magic, mystery, and Icelandic folklore. In this article, we’ll explore the history of Icelandic runes, their meanings, and their role in local myths and culture.

Key Takeaways

-

There were multiple runic alphabets throughout history, which are important to know when learning about Icelandic symbols and their meanings.

-

The Icelandic rune was believed to have magical properties and was used throughout Iceland's history and even by figures across mythology and folklore.

-

Runes were arranged together to create Icelandic staves, which were used to make magical spells.

-

Icelandic magic runes have also been used for fortune-telling purposes, offering some insight and guidance into future events.

-

The Icelandic runes' alphabet still persists to the modern day, as several characters in the Icelandic language are directly taken from runic letters.

A Brief History of Runes

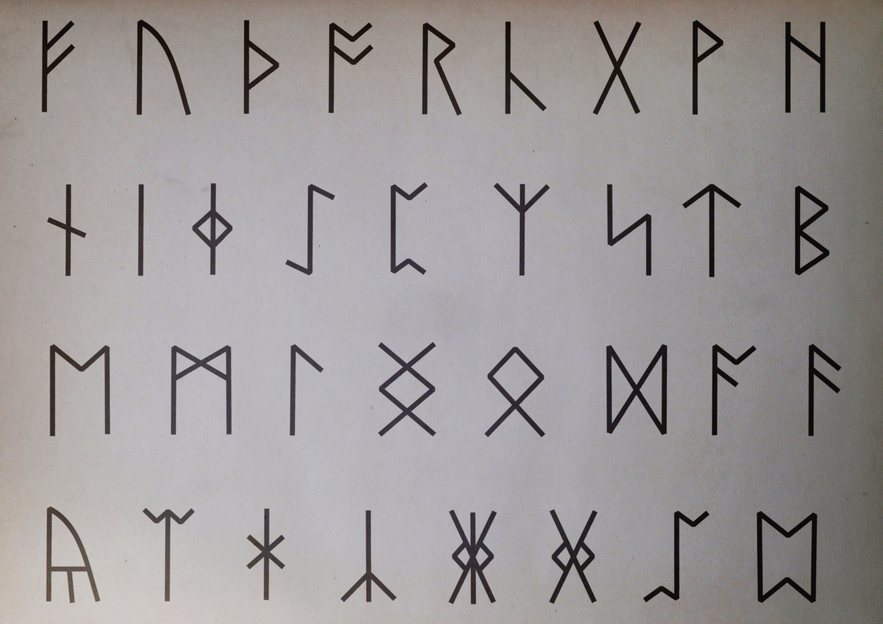

There's not only one Nordic runic alphabet. There are several. They're known as Futhark, a name that comes from the first 6 letters of the alphabet.

The first fully formed of these alphabets is the Elder Futhark, which consists of 24 symbols and was in use between the 2nd and 8th centuries CE.

Then, in the late 8th century, or around the beginning of the Viking Age, a shortened variant of only 16 runes replaced the Elder Futhark in Northern Europe. This shorter version became known as the Younger Futhark or Scandinavian Runes.

When Iceland’s Age of Settlement began around A.D. 870, these runes became the basis of the Icelandic runic alphabet.

The oldest runes found in Iceland date back to the 10th century, but since the oldest historic sources in Iceland frequently mention runes, the Eddas, and the Icelandic Sagas, we know they've been here from the beginning.

In the eyes of those used to the Latin alphabet, runic symbols can appear perplexing. One symbol can have two or more sounds or even represent whole words or phrases.

In this way, they resemble other ancient forms of logographic writing, such as Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Additionally, the characters weren't necessarily written from left to right. Sometimes, runes were written from right to left or top to bottom. Furthermore, they could change directions or be drawn horizontally as opposed to vertically, and often, strings of words would not be separated by spaces.

Many runologists believe that these variants affected the meaning of the inscriptions. Essentially, runic writing was less straightforward and more cryptic than the writing systems we've grown accustomed to today.

During the Christianization of Europe, the spread of the church brought major changes to language and culture. As religious texts like the Bible were copied and shared widely, the Latin alphabet became the dominant writing system. Over time, this left little space for the older and more mysterious runic scripts, which gradually faded from everyday use.

Additionally, runic characters consisted of straight lines that made them ideal for wood, stone, and bone carvings (the very word "rune" means to carve or cut). As such, the runes were perfect for marking or blessing objects and casting spells, but could hardly be used to convey volumes upon volumes of the written word.

During the Viking Age, stories were traditionally passed down verbally, which is why stories like the Icelandic Sagas were only written down several hundred years after the events they described took place.

In the new world order, the Latin alphabet simply proved more efficient, and writing in ink on parchment largely replaced the practice of carving runes on hard surfaces.

The continued use of runes throughout history is largely thanks to their mystical meaning and visual appeal. Runes were carved onto doorways, weapons, and relics—not just for writing, but to offer blessings and symbolic protection that the Latin alphabet couldn’t convey.

For centuries in Northern Europe, runes and Latin script coexisted, each serving different purposes.

Historians have long been intrigued by the presence of Icelandic runes on Christian objects like church relics and tombstones. Since Norse mythology describes runes as gifts from pagan gods, their use alongside Christian symbols raises an interesting question: Did these two belief systems quietly coexist in Iceland for a time?

Approximately one hundred archaeological examples of rune carvings in Iceland have been unearthed or preserved to date. These include one of the nation's most treasured relics, the Valthjofsstadur door, a wooden church door dating from around A.D. 1200.

Currently on display in the National Museum of Iceland, the door showcases the use of runes as an integral part of everyday life in Iceland, even centuries after the nation had converted to Christianity.

Runes were used for decorative purposes until 1592, when Bishop Oddur Einarsson issued the ruling of “Kýraugastaðasamþykkt”, which aimed to eliminate old Catholic and other non-Protestant traditions.

Runes were used for decorative purposes until 1592, when Bishop Oddur Einarsson issued the ruling of “Kýraugastaðasamþykkt”, which aimed to eliminate old Catholic and other non-Protestant traditions.

This included a ban on all forms of magic, or galdur—even healing magic (lækningagaldur), which preserved elements of early medical knowledge.

At the time, the lines between science and magic were not as clear as they are today. Runes were used not only as a writing system but also as tools believed to serve practical, even medicinal, purposes.

The outlawing of runes reached its peak during the 1600s Age of Fire, when 21 Icelanders were burned at the stake for practicing witchcraft. Intimate knowledge of the magical runes was enough to earn a person the label of witch or sorcerer.

The Icelandic witch trials differed from their European counterparts in that the victims were mainly men. The first person executed for witchcraft in Iceland was Jón Rögnvaldsson, who was accused of summoning a ghost to haunt his neighbor. Authorities found runic scrolls and mysterious drawings in his home, which were used as evidence to convict him.

- See also: The Most Infamous Icelanders of History

Today, runes constitute a vital part of Iceland's heritage and identity, especially since the foundation of the Asatru Fellowship (a religious association devoted to Norse mythology) in the 1970s.

But what were the magical elements of the runes that worried the church?

The Magic of Runes

Although the Latin alphabet may be more efficient and practical for writing, the runes convey much more than simple sounds and vowels. They're potent symbols that carry great magical properties, handed down from the gods themselves.

Several heroes of the Icelandic Sagas and Eddas use runes for magical purposes.

Examples are found in Sigrdrifumal, a section of the Poetic Edda, in which the Valkyrie Brynhildur helps the hero Sigurdur on his road to glory by teaching him several magical runes, including:

-

Victory runes to be carved on swords before a battle.

-

Wave runes to be engraved on the helms of ships.

-

Speech runes to prepare one's rhetorical abilities before a Thing assembly.

These mystic runes often had names that explained their magical purposes, and some of them are traditional Icelandic female names to this day.

For example, Hugrún, composed of the words hugur (mind) and run (rune), was meant to increase one's wit, while Sigrún, consisting of sigur (victory) and run (rune), was meant to help in the winning of battles.

One of the greatest Vikings of the Icelandic Sagas, Egill Skallagrímsson, was a master of runes and their magical properties. This knowledge was vital to his many outstanding abilities.

In the Saga of Egill, he visits a farmer's daughter who has fallen gravely ill. Egill notices evil runes carved on a whalebone above her bedpost. He destroys the runes and carves out new ones, saving the girl's life before noting that runes should only be used by those who possess the correct knowledge.

On another occasion in the Saga, Egill uses runes and a protective spell to shatter a poisoned cup meant for him at an enemy's feast. The message of these passages is clear: with runic knowledge comes great power, on par with being a skilled fighter and strong warrior.

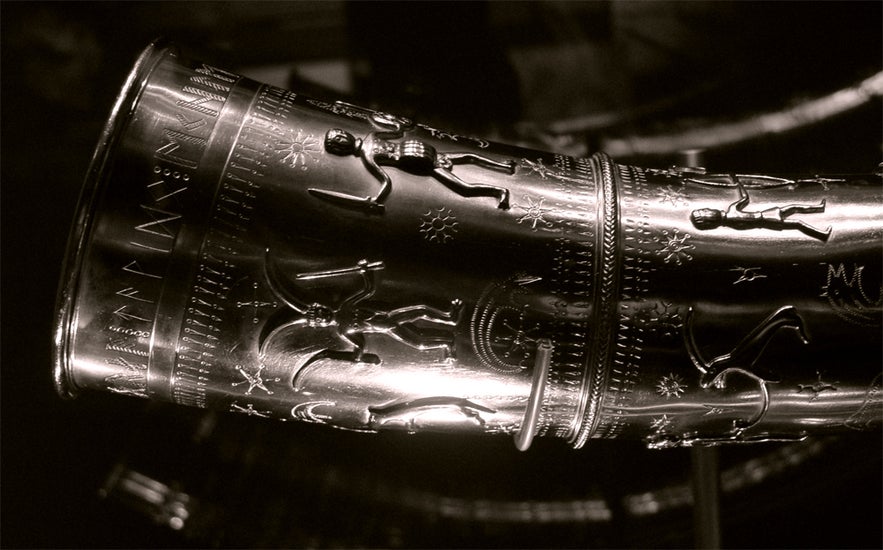

In European archaeological discoveries, dating back to the Germanic Iron Age and Anglo-Saxon England, the runic sequence ALU has been found carved on various surfaces, including stone, wood, animal horns, and weapons.

Although the word's exact meaning is disputed, most historians agree that it represents magic and divine inspiration and that the sequence counts as the most common of all runic charm words of old.

ALU appears both alone and as a part of more elaborate combinations. The first letter is called "as" or Ansuz; it's Latinized as "A" and usually represents a god or divinity and a tree, such as oak or ash.

In Norse cosmology, the tree of life, Yggdrasil, grows through the entire world, connecting its nine realms. When you consider that Yggur is one of the many names of Odin, suddenly, the same letter, representing both gods and trees, starts to become clearer.

In Norse cosmology, the tree of life, Yggdrasil, grows through the entire world, connecting its nine realms. When you consider that Yggur is one of the many names of Odin, suddenly, the same letter, representing both gods and trees, starts to become clearer.

The carving of a rune carried with it a whole network of symbolism and connected meanings that can only be understood by those who studied them extensively.

In the Codex Regius poem Havamal, Odin was one such seeker of knowledge. He is said to have endured great physical suffering in exchange for learning the secrets of the runes. For nine days and nine nights, Odin hung from the branches of Yggdrasil, impaled by his own spear and deprived of food and water.

After this great trial, the magic of the runes was revealed to him. According to the poem Rigsthula of the Poetic Edda, the god Heimdallr passed down Odin's knowledge of the runes to selected members of the human race.

- See also: Where Did Icelanders Come From?

The Germanic people of ancient times didn't think of the runes as having been invented. Instead, they were seen as pre-existing forces handed down from eternity.

This divine origin of the runes tells of the power they behold. Each rune carries a link to a Norse mythological figure, an important animal, or a natural element, and knowing how to read them unlocks wisdom that verges on magical abilities.

Icelandic Magical Staves and Runic Readings

Throughout their history, runes were not only used for magical purposes. They were considered magical by their very nature. They promoted communication, not only among people but between humankind and gods, allowing for a conversation with the hidden powers of the world.

When one gains an in-depth understanding of the characters, one can start arranging them together to increase their power and create potent magical formulas. These more complicated sigils are known as Galdrastafir or "staves."

The spells conducted with these Icelandic symbols were known as “seidur,” and the practitioners were called seidmenn (male) and seidkona (female). Most of the time, their sorcery consisted of good magic and was designed for personal aid and the benefit of others.

Most runic staves were to be carved on specific surfaces, such as a particular metal or wood. After carving, the spells usually required the anointing of the symbols with blood, also of a specific type, such as from the little finger of your right hand.

The use of blood might sound morbid, but it's merely representative of the sacrificial aspects of runic knowledge, which is a reference to Odin's original suffering when hanging from the branches of Yggdrasil. To maintain the universe's balance, you have to give something away to get something back.

Let's take a quick look at two of the most popular Icelandic magical staves, their origins, and their powerful uses.

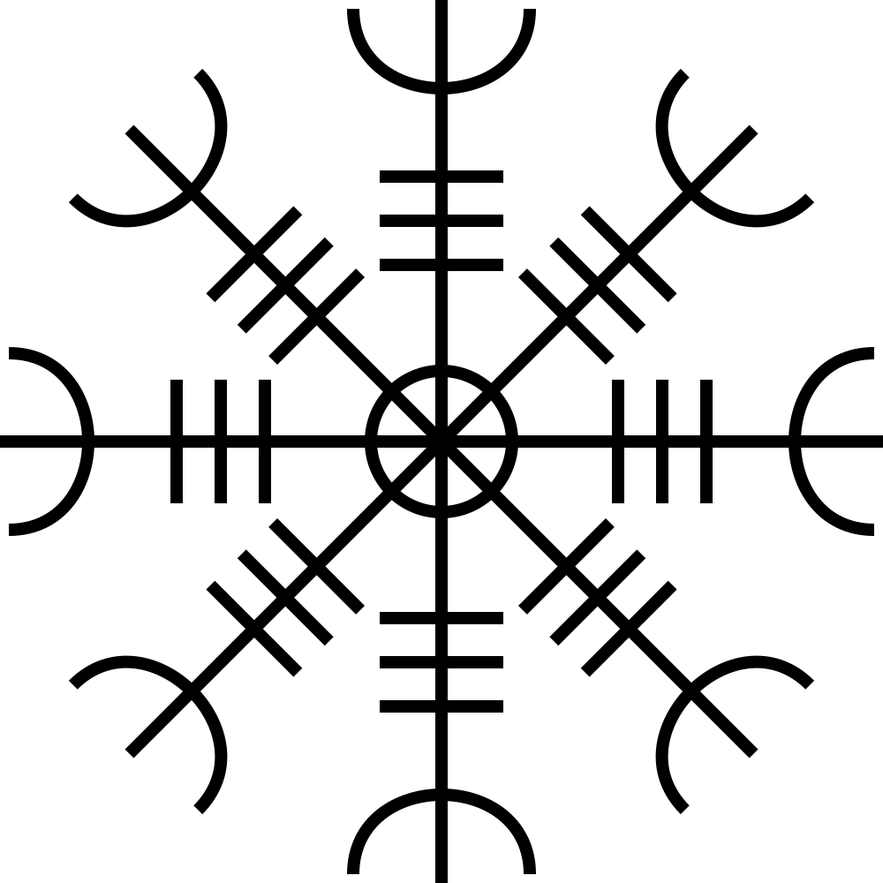

Aegishjalmur

Aegishjalmur, or the Helm of Awe, is probably the most well-known stave in modern Iceland. You'll see it carved into jewelry and printed on T-shirts. It's perhaps the most popular tattoo choice amongst those interested in Nordic culture and history.

The carving of Aegishjalmur is believed to possess powerful qualities of protection against evil and injustice. It was used by warriors of old to induce fear in their enemies' hearts and prevail in battle.

In the Fafnismal poem of the Poetic Edda, the formidable dragon Fafnir uses the stave to defend his treasure from enemies.

Looking at the symbol, one can easily imagine eight arms or tridents reaching out from a central point and shielding it. The arms bear the appearance of the Madr rune (Latin M or Mannaz) in the Younger Futhark or the Elgr rune (Latin Z or Algiz) in the Elder Futhark.

The former represents humanity, while the latter is an elk whose horns symbolize courage, power, and self-defense against predators.

An example of utilizing this stave with a spell is found in Jon Arnason's collection of Icelandic Folk Tales and Fairytales. There, one is instructed to carve the helm in lead, press it between one's eyebrows, and speak the following spell:

“Aegishjalm er eg ber, milli bruna mer.”

("I bear the helm of awe between my brows.”)

Try it out before your next confrontation with an adversary, and notice your heart filling with courage and your spirit soaring toward victory!

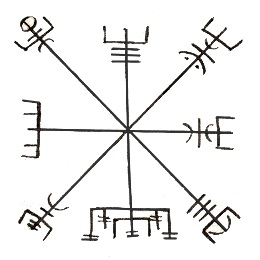

Vegvisir

Vegvisir, or Wayfinder, is a stave born out of the conditions of Icelandic nature. Its purpose is to aid its bearer through rough Icelandic weather and storms, helping whoever carries it to find their way home in unfamiliar surroundings.

This rune stave is quite popular today despite it only being found in a single collection of spells, the Huld Manuscript, written by Geir Vigfússon in 1847. He gathered the material from earlier works. Since no other collection showcases this stave, its age is unknown, although it's not considered very old.The Wayfinder has been called a Runic Compass due to its appearance. But as is imminent from the Helm of Awe, many rune staves form an eight-pointed wheel, so this is most likely coincidental. The spirals are more varied in the Wayfinder and harder to interpret, but the Madr (man) rune is distinctly visible again.

This verse from the Poetic Edda's Havamal might shed some light on the symbol's runic significance:

“Ungur var eg fordum, for eg einn saman, tha vard eg villtur vega;

Audigur thottumk, er eg annan fann, madur er manns gaman.”

("Young was I once, I walked alone, and bewildered seemed in the way;

Then I found me another, and rich I thought me, for man is the joy of man.”)

For what better way is there to find one's way than with the help of a fellow human being?

Icelandic Runes for Fortune Telling

The use of runes to read the future can be likened to the customs of tarot card readings or astrological charting. These readings don't offer any clear answers but rather instructions on how the subject's future can be met or affected.

There are several ways of going about this practice, but let us examine the reading of one rune at a time to introduce how to interpret the answers provided. When reading prophecies through runes, three representatives from Norse mythology provide three different guidelines.

The first is a trio of foreseeing Norns known as Urdur, Verdandi, and Skuld. In Norse lore, these women are in charge of the destinies of gods and men as they spin the threads of fate at the foot of the world tree, Yggdrasil.

The second representative is the hawk Vedurfolnir, who glides above Yggdrasil's branches, representing all that is good and noble. His readings of the runes tell of the positive aspects of the prophecy at hand.

Let's try this out. Say you possess a collection of stones, each engraved with a rune. You reach for one, and the destiny's hand you the letter Jor (Latin E or Ehwaz).

This is the rune of Sleipnir, Odin's eight-legged horse. The rune then represents the movement or a journey, either in the literal form of traveling or perhaps as an inner journey of the mind.

The Norns would tell you your life is about to move forward, that things are on the verge of change, and barriers are about to be broken. Vedurfolnir would advise you not to fear the unknown, to grab whatever chances come your way, and to be steadfast on your travels.

Lastly, Nidhoggur would tell you to be wary of impatient acts such as recklessness or folly.

The wisdom of runic readings lies in the subject self-reflecting on their nature or environment, bearing in mind that there is always more than one route to each destiny or destination.

Runes in Modern Iceland

The Icelandic alphabet of today is a Latin one, with the addition of ten extra letters in comparison to the English alphabet. Some are simply Latin letters with acute accents, but some are letters in their own right, known as serislenskir (specifically Icelandic) characters.

Out of these, Þ is quite literally a runic letter. It has been present in many historical languages, including Old Norse and Old English, but today, it's not a part of any living language except Icelandic. Þ was widely replaced with Th since it's pronounced as such, for example, in the English word "theater."

The rune that birthed this letter is the Þurs or Thurisaz rune, belonging to Thor's hammer, Mjolnir, which the thunder god used to slay the giants of Norse mythology known as þursar. This rune represents awe, terror, destruction, or conflict in runic reading.

In Icelandic, a softer version of Þ is Ð, pronounced like Th in "they." It was interchangeably used with Þ in Old English, but unlike Þ, Ð is a modified Roman letter as opposed to a runic character.Another notable character in the Icelandic alphabet is Æ (pronounced Ai). The letter comes directly from the Old English alphabet, but as such, its origin is the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc rune as or Ansuz — the rune of Odin and the ash tree Yggdrasil.

The word still represents the Norse gods in Icelandic, and the plural of that word takes the form of Æsir, pronounced ice-ir. Some have even suggested that Iceland got its name not from the natural elements of ice and snow but from the very gods the country's first settlers worshipped.

The Icelandic magic runes represent the power of the spoken and written word, the competency of knowledge, and the brimming symbolism of mythical entities. Iceland was founded on these symbols, the Sagas boast of their powerful qualities, and legendary folk tales tell of their hidden sorcery.

Learn About the People Who Used Icelandic Runes and Staves Through Firsthand Experiences

One of the best ways of learning more about Icelandic runes and their meanings and folklore in Iceland as a whole is by experiencing it firsthand. The land of ice and fire is home to numerous cultural tours that are a great opportunity to learn more about the people who used runes and staves and how they lived their lives.

Iceland Museum Experiences

There are numerous museums across Iceland that are a must-see for visitors who want to learn more about the early settlers who shaped the country's history and laid its foundations.

There are numerous museums across Iceland that are a must-see for visitors who want to learn more about the early settlers who shaped the country's history and laid its foundations.

-

Visit the Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft — Learn all about magic in Iceland with a visit to the iconic Witchcraft Museum, a must-see location on Westfjords tours.

-

Entrance Ticket to Viking World Museum on the Reykjanes Peninsula — At the Viking World Museum, you'll learn about the people who first settled Iceland, a replica of a Viking ship, and more.

-

Experience the Settlement Period Farm of Eirik the Red and Leif Eiriksson — Step into the past on this memorable tour of a settlement period farm replica.

-

Settlement & Egils Saga Exhibition in Borgarnes — On this engaging museum tour, you'll learn about Iceland's distant past and the famed Egils Saga.

Icelandic Culture Tours

Want to immerse yourself in Icelandic culture? These guided tours are an excellent way to learn about the history of Iceland.

Want to immerse yourself in Icelandic culture? These guided tours are an excellent way to learn about the history of Iceland.

-

Viking Walking Tour of Reykjavik — Explore Reykjavik and learn more about Iceland's Viking past on this memorable walking tour of the capital.

-

Folklore Walking Tour of Reykjavik with Tales of Trolls, Elves & Hidden People — If you're interested in learning more about Icelandic folklore, this guided tour will share many fun facts and lore.

-

Small Group Walking Tour of Reykjavik's History & Culture — Discover the history of Reykjavik, Vikings, and more during this memorable guided tour.

FAQs About Icelandic Runes

Here are some frequently asked questions about Icelandic runes.

Are Norse Runes Painted?

The word "rune" means to carve or cut. As such, Norse runes were typically carved into wood, stone, or metal.

However, that doesn't mean they were never painted on. In fact, traces of paint have been found in the carved lettering of many runes. Further, many Nordic runestones themselves directly state that they were painted on.

Where Can Icelandic Runes Be Seen?

Icelandic runes can be found in various historical sites and museums throughout the country. One of the best places to see artifacts with historic runes is the National Museum of Iceland in Reykjavik.

From Past to Present, Icelandic Runes Have Shaped the Land of Ice and Fire

In all likelihood, and in some form or another, the runes and their magic will always reside with the Icelandic people and their culture!

Did you enjoy our guide to Icelandic runes? Is there anything we missed? What's your favorite magic stave? Tell us your thoughts by writing in the comments section below!