A History of Reykjavik

How did the world’s northernmost capital city grow from a farmstead to a bustling cultural centre that hosts two-thirds of Iceland's population? Read on and discover all you need to know about the history of Reykjavík.

- Stuck with a rainy day in the capital? Check out Reykjavik Escape

- Learn more about Iceland's History

Today, Reykjavík is known as a vibrant, quirky place, that melds a small-town vibe with big city living. Almost every visitor to Iceland will pass through, and the vast majority will stay at least one night. People come to see its cultural sites, to enjoy its festivals, to appreciate the cuisine and nightlife, and to use it as a base to see the rest of the country.

It seems natural that such a dynamic city would develop from the first place on the island to be permanently settled; it has had the potential to grow for over a millennium.

For the majority of its history, however, Reykjavík did not reflect its monumental beginnings or its grand future; it was a hub of wool production in a nation that was centred around fish. Its journey to where it is today has been shaped by colonialism, war, trade and migration, largely over the past three hundred years.

- Read also: The History of Iceland

Settlement Era

Almost everything we know about Iceland’s earliest history comes from Landnámabók, also known as the Book of Settlements, composed by Ari Þorgilsson in the late 11th or early 12th Century. It records the first people to come to Iceland, where they settled, and who their descendants were in meticulous detail. It is from this that we know that Ingólfur Arnason and Hallveig Fróðadóttir were Iceland’s first permanent settlers and that they settled in Reykjavík.

They established their home in 874, but choosing Reykjavík was not a random decision. To decide where he and his family would settle, Ingólfur threw his high seat pillars, the symbols of his chieftainship, into the sea, and scoured the coast to see where they would land. The location he found them was dotted with many steaming hot springs, and he named his new home after them; the direct translation of Reykjavík is ‘Smoky Bay’.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Willem van de Poll. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Willem van de Poll. No edits made.

Ingólfur was very influential throughout his life and revered afterward. He owned a vast amount of land that he expected would keep his family in dominance for a significant period following his death. For a while, this would be the case.

The male descendants of Ingólfur and Hallveig were given the title ‘Allsherjargoði’, which meant they were religious and political leaders. The family would be instrumental in starting collective governance in Iceland. They formed the Kjalarnes Assembly, which united the chieftains of the south-east and was used to settle disputes between them civilly, rather than with violence.

It was a successful institution but seen as too dominant by other clans and similar assemblies around the country, who sought a National Assembly, whereby power would be spread across the nation, rather than consolidated in Reykjavík. The descendants of Ingólfur and Hallveig were willing to help and were instrumental in the formation of the Alþingi in 930 AD.

The creation of the Alþingi was momentous; it established an Icelandic Commonwealth, marked the end of the Settlement Era, and began what is today the world’s longest-running parliament. It, however, also had its desired effect on the power balance in the country.

Because of the number of Ingólfur’s descendants, the land he owned was broken down more and more with each passing generation. After 1000 AD, records of the family and their properties begin to disappear. It would be over 700 years before Reykjavík emerged from obscurity and started to reclaim its title as the center of Iceland.

Commonwealth to Colony

In the late Middle Ages and Early Modern Period, Reykjavík had little presence on the Icelandic stage, let alone the international one. The island itself went through huge changes, however, going through Civil War then being absorbed into the Kingdom of Norway in the 13th Century. After that, it was consolidated into the Kalmar Union (the Scandinavian Union dominated by Denmark) in 1380 and continued to be subject to the Danish Crown after the union dissolved.

The nation also went through religious strife throughout this time. The 11th Century was dominated by the island’s conversion to Christianity, and the 16th by the Reformation, which turned the country Lutheran. Following the Reformation, there was somewhat of a power vacuum; two Episcopal Sees had replaced Reykjavík as the most influential places in the country, and without the faith behind them, they lost relevance.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Jon Gretarsson. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Jon Gretarsson. No edits made.

The strife these problems brought to Iceland, and problems that already existed such as limited resources and a volatile climate made the lives of the locals very challenging. This was worsened by their lack of economic independence. Denmark, over time, had strengthened its hold over the country’s lands, and the crown had a complete trading monopoly.

Colony to Independence

Reykjavík’s rise back to power started with one new arrival; Dane Skuli Magnusson moved to the farmland in the 18th Century and established wool workshops, which brought work to the area and meant that the products were of high quality. This did not go unnoticed by the Crown authorities; when trading charters started to be provided to Iceland’s settlements in 1786, Reykjavík was the only one to get a permanent one.

It grew significantly as a port over the next decades, to the extent that when the Alþingi, which had been suppressed for fifty years from 1798, was reestablished, it was rehomed in Reykjavík. This returned power to the south-east and made the ‘town’ (really an assortment of government buildings, shanty houses, and farms) the capital of the colony.

Reykjavík’s economy was boosted further in 1855 when the Crown declared they could engage in free trade with all nationalities. Icelanders gained more economic independence with their first Constitution, codified in 1874, and, more significantly, with the end of the Danish Monopoly in 1880.

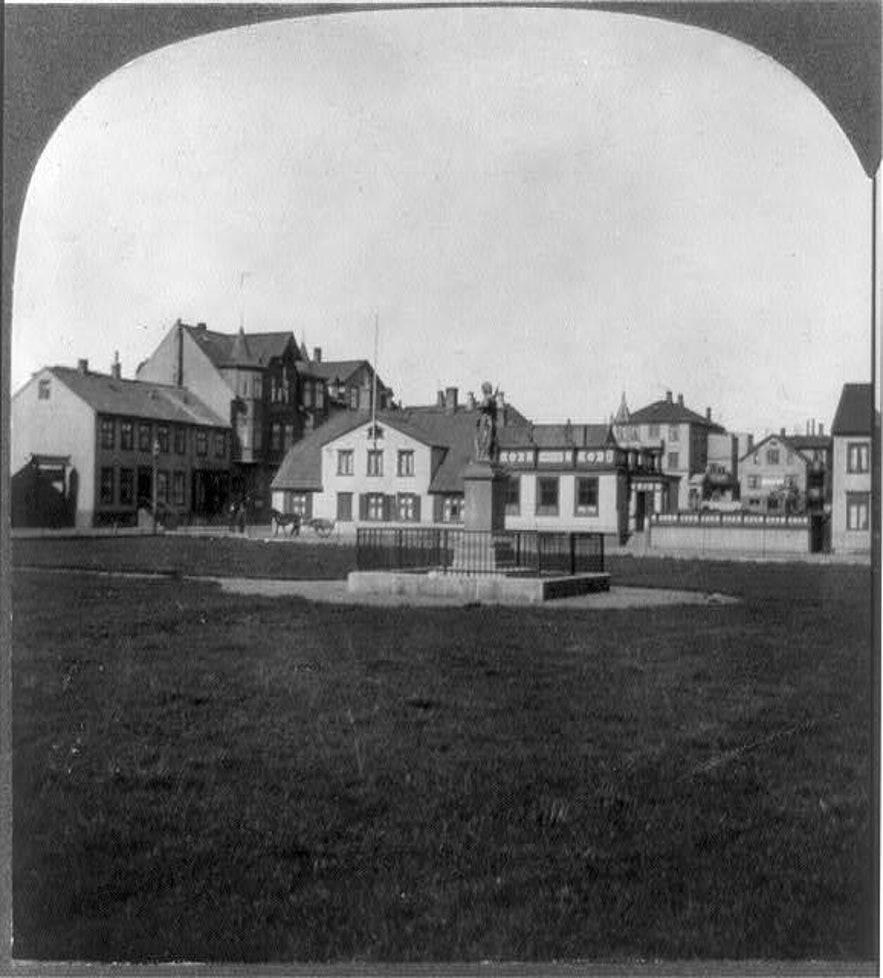

Photo from Keystone View Company

Photo from Keystone View Company

For the first time in Icelandic history, people started using cash to exchange for goods, rather than just bartering their possessions. Considering Reykjavík was by far the country’s biggest port, most of the money was changing hands here.

While these factors edged the capital towards modernity, the biggest booms it would go through would come during the first half of the twentieth century, when the rest of the world engaged in war. From 1914 to 1918, Iceland’s wool was in huge demand, as the fields of Europe were ravaged with fighting, allowing the agricultural industry to explode.

The enormous benefits that came with this stayed largely in the hands of the locals, as at the end of the war, Iceland was liberated from its burden of being a colony; Denmark granted it Home Rule in 1918, and it was renamed the Kingdom of Iceland.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by the Swedish National Heritage Board. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by the Swedish National Heritage Board. No edits made.

The interwar period, however, was hard for many rural Icelanders, as the majority of the land was now in the hands of the very wealthy; they had raised enough to purchase modern agricultural equipment, and the common person simply couldn’t compete. Therefore, a mass movement to Reykjavík gained traction.

World War Two’s arrival also helped Reykjavík and wider Iceland; with the navies of the world battling, there was a huge demand for a reliable source of fish amongst the Allies. This, Iceland could provide, even after it lost contact with Denmark following its occupation by the Nazis. Because of its strategic location in the mid-Atlantic, Britain invaded Iceland in 1940, helping to protect these fisheries, before the US took over the protective occupation in 1941.

In 1944, Iceland declared its complete independence from Denmark. When the war ended, against the protests of the Crown, they refused to re-enter the Kingdom. From that point on, Reykjavík was the official capital of a newly independent Iceland. In 1945, it was on the brink of a cultural, social and economic explosion.

Post-War Era

At the end of World War Two, Iceland was at a strange crossroads. It was more prosperous than it ever had been, yet still hugely reliant on fishing and agriculture in an increasingly technical world. It was independent for the first time in 700 years, yet without any national armed forces, and it was located in a precarious position between the two newly sparring superpowers of the USA and USSR.

The US troops that remained in Iceland, however, would help the nation develop dramatically. With no intention to leave considering the start of the Cold War, the Americans stationed in Keflavík wanted to be able to drink, dance, eat out and attend cultural events; they found Reykjavík scene, however, incredibly barren.

Therefore, they worked to change it. Bars started opening downtown to entertain the military personnel over the weekends, and as many Icelanders began to attend them and extend their social lives, they became enraptured. The isolationist mindset that had dominated the country for centuries gave way to an interest in international culture and influences.

That is not to say the US base was uncontroversial; the 1949 protests against joining NATO were some of the largest and most violent the country have experienced to date. Many Icelanders rejected those who embraced the American ideals, particularly ostracising the women who took American men as lovers and partners.

Many of the women of Reykjavík, however, were more interested in men who wanted to dance, rather than those who wanted to fight. This forced the stubborn, rural Icelandic men to develop into the modern 'renaissance men' they are today.

With money coming into the country from American taxes and growing trade, Reykjavík started to develop stadiums and centres where athletes could train. These sportsmen began to compete abroad and found themselves rather able when it came to athletics. The city also began to invest in the arts; in 1950, the National Theatre was opened, and the National Symphony Orchestra started up. Different festivals began to take place, and by the 1960s, Reykjavík was becoming quite a modern city.

In this decade, electronics and automobiles became more widespread. Flights to and from Europe allowed people to discover this new land, and Icelanders could develop knowledge of the outside world. As conditions in Reykjavík grew better and better. However, half of the population noticed their advancements were limited when compared to their counterparts. Their resulting protests would help solidly put Iceland and its capital on the map.

The 1975 Women’s Day Off shocked the Reykjavík establishment, and the effects resonated around the world, inspiring similar movements and strikes. Icelandic women, sick of the fact that their working population earned sixty percent of what men did, and that they were bound to domestic labour, went on strike. They refused to go to their jobs, do the housework, or raise the children.

- Read more about Gender and Gender Equality in Iceland

The effects were far-reaching. It was one of the first times that the city had engaged the international news media, largely because such a protest had been unseen before. Following this event, the world started to keep an eye on Iceland.

The attention turned into a furor in 1986, when President Reagan of the US and Chairman Gorbachev of the USSR met in Hofdi House for the Reykjavík Summit. The discussions were largely to do with banning ballistic missiles but also covered issues such as human rights, the emigration of Soviet Jews, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. While the talks fell apart, both sides saw the concessions the other was willing to make, and many consider this summit to mark the beginning of the end of the Cold War.

Photo by Einar H. Reynis

Photo by Einar H. Reynis

Attention in Iceland continued to increase after this, as did tourism, and the nation’s economy; as a result, the city’s sports, arts, and culture flourished. In 2000, Reykjavík was named one of nine European Cities of Culture.

Such an enormous boom, however, could not come without a significant bust. Iceland faced this with the rest of the world in the 2007-8 financial crash, although much more severely than many other places - to the extent it seemed that the country would be crippled beyond recovery.

Icelandic banks had undergone a rapid and reckless expansion over the preceding years, accumulating debts that totalled over seven times the entire GDP of the nation. Most of this debt was to the UK and the Netherlands, which Iceland seemed unable to pay when the banks collapsed. The decision to bail them out so that these funds could be restored regardless, however, did not sit with the Icelandic people, who would bear the consequences over many years in taxation.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by OddurBen. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by OddurBen. No edits made.

What started as a one-man protest by singer, activist and queer rights pioneer Hörður Torfason became the largest protests the nation had ever seen at the time. Thousands of people - including the wife of the then-President - engaged in demonstrations that were destructive, persistent, and effective.

Called the ‘kitchenware revolution’ due to the amount of banging of pots and pans, many politicians were forced to resign, a new constitution was written, eighteen of those complicit in the crash were imprisoned, and the government was forced to refuse to pay back the UK and the Netherlands outright. These nations took Iceland to the Court of Justice of the European Free Trade Association States to try and make them pay and lost.

By 2010, the depression was still ongoing, even though the new measures were protecting the people from the effects of the crash, so that their situation was more comfortable than in places such as Greece and Portugal. This is the year, however, when the volcano Eyjafjallajökull erupted, causing an international media storm as flights were delayed for days and thousands were stranded. As negative as this attention sounds, it was, in fact, an enormous blessing.

Photo by Marc Szeglat

Photo by Marc Szeglat

Suddenly, everyone wanted to come to Iceland, and after the novelty of the eruption had worn off, such a number had come to visit that the country could sustain its tour industry by word of mouth. As such, Iceland’s economy was pulled back from the brink, and Reykjavík was able to secure itself once more as a thriving capital city.

Reykjavík Today

Reykjavík today is at its peak. More visitors than ever are arriving and enjoying its sites, opportunities, and culture. The city is alive with musicians, comedians, theatre actors, filmmakers, drag artists and burlesque performers; its art and architecture are thriving, and its museums, concert halls and galleries are bustling.

Not only this, but Reykjavík has developed into an incredibly welcoming city. Iceland has been listed as the safest country in the world by the Global Peace Index ten times. The Global Gender Gap Index ranked it as the most gender-equal for the past eight years running, and it is widely considered one of the most comfortable places in the world to be queer.

Considering that two-thirds of Icelanders live in Reykjavík, these facts speak volumes about the nature of the city.

Reykjavík is also now a festival capital of the world; both residents and visitors flock to events such as the Reykjavik Arts Festival, Iceland Airwaves, Gay Pride, RIFF (The Reykjavik International Film Festival), Culture Night, and Food & Fun.

The more visitors that come here, the more things are likely to continue accelerating. It is just the hope of Icelanders that Reykjavík will remain their city to enjoy as well, in the sense that they will still be able to afford the cost of living as accommodation is turned into Airbnbs and the downtown area starts to cater to tourists rather than residents.

From settlement today, however, Reykjavík has truly established itself as the political, cultural and social center of Iceland, with no close competitor. When Ingólfur Arnarson found his high pillars in this smoky bay, it is impossible that he ever could have imagined the heights to which his farm would ascend.

Weitere interessante Artikel

Die besten Restaurants in Reykjavik

Welches sind die besten Feinschmecker-Restaurants in Reykjavik? Wo kannst du die traditionelle isländische Küche erleben? Welches sind die besten internationalen Restaurants in der Stadt? Für jedes...WeiterlesenDie besten Schwimmbäder in Reykjavik

Möchtest du die besten Schwimmbäder in Reykjavík finden und die besten Orte zum Eintauchen in Hot Pots entdecken? Lies weiter, um mehr über Islands einzigartige Schwimmkultur und die besten öffentlich...Weiterlesen

Die 10 besten Museen in Reykjavík | Geschichte, Kultur & Wikinger!

Welche sind die besten Museen in Reykjavík? Geht es dort nur um Wikinger, Wale und Elfen? Gibt es in Reykjavik wirklich ein Penismuseum? Hier findest du einige der besten Museen in Reykjavik, die d...Weiterlesen

Lade Islands größten Reisemarktplatz auf dein Handy herunter, um deine gesamte Reise an einem Ort zu verwalten

Scanne diesen QR-Code mit der Kamera deines Handys und klicke auf den angezeigten Link, um Islands größten Reisemarktplatz in deine Tasche zu laden. Füge deine Telefonnummer oder E-Mail-Adresse hinzu, um eine SMS oder E-Mail mit dem Download-Link zu erhalten.