Contrary to popular belief, the majority of Iceland's power production is not geothermal but hydroelectric. Plans are now in motion for eight new hydroelectric power plants that will dam the country's glacial rivers to feed the needs of a steadily growing heavy industry.

- Check out this Exciting Rafting Tour in North Iceland

- Read this Ultimate Guide to River Rafting in Iceland

What is the future of the country's river systems, and what is the enduring influence of heavy industry here? Read on to discover the inconvenient truths about Icelandic power production and learn how you, as a traveler to Iceland, are a part of the solution.

Why You Can Trust Our Content

Guide to Iceland is the most trusted travel platform in Iceland, helping millions of visitors each year. All our content is written and reviewed by local experts who are deeply familiar with Iceland. You can count on us for accurate, up-to-date, and trustworthy travel advice.

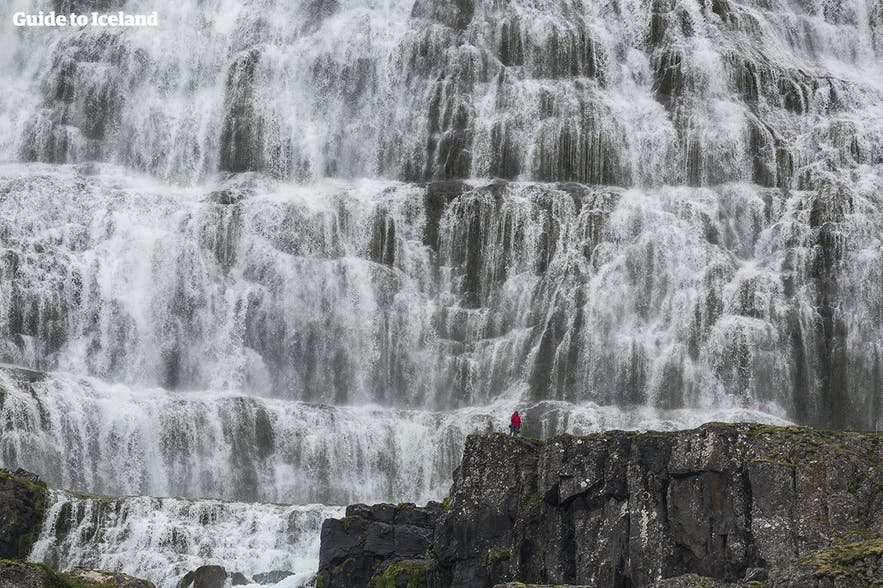

Every year, visitors from all over the world flock to Iceland for its unparalleled natural scenery. As an island only inhabited along its coastline, and with very few residents, the country primarily consists of unspoilt terrain, dotted here and there with geological wonders, be they active volcanoes, magnificent glaciers or cascading waterfalls.

Icelanders have long held these treasures in high regard. Most permanent capital city residents always hold one foot in the countryside, nurturing a powerful and heartfelt link to nature. Far from merely aesthetic merits, the natural wonders of this country’s young terrain are interconnected, pulsing with life and bursting with great power.

From erupting volcanoes to glacial outbursts, the elements of Iceland have always challenged local survival as well as enabled it, accumulating in a native relationship that balances awe and gratitude in equal measure.

- See also: Volcanoes in Iceland

One of the island's many gifts is its geothermal activity. Hidden beneath the land's delicate soil is a rushing network of raw power where the constant continental rifting and high concentration of active volcanoes provide optimal chances for the conduction of thermal energy.

A series of low-polluting power stations then capture this energy in the form of heat, transported from underwater reservoirs up to the planet's surface.

That is why, around the world, Iceland is considered something of a paragon when it comes to renewable energy. Serving as a shining example of geothermal power production, many deem us a role model in regards to environmental sustainability.

Over 90% of Icelandic homes get their energy from geothermal power, but when it comes to industry, it's another story altogether. In fact, only 27% of the energy generated in Iceland is geothermal, while the lion's share of the rest is hydroelectric.

Hydroelectric power is also considered a fairly renewable energy source. It utilises water without consuming it, produces no direct waste and the output levels of greenhouse gases measure very low in comparison to energy plants powered by fossil fuels.

With that said, creating a hydroelectric power plant means building massive dams and reservoirs, cultivating vast areas of land and redirecting water on a grand scale.

For the construction of Kárahnjúkar Hydropower Plant in East Iceland, five dams in two glacial rivers created three reservoirs, that together flooded over 440,000 acres of unspoilt Highland territory. The megastructure is on a scale like nothing the nation has seen before or since and, as such, has been a constant source of protest and controversy due to the landscapes irretrievably lost.

But could the sacrifice of select areas of land be deemed necessary for power production? After all, if the energy is green and its power needed, a redirection of a river or the flooding of a valley might not sound like the end of the world. However, the question remains as to if a true necessity for power already exists, or if it's being created with the development of heavy industry across the country.

Iceland's Hydroelectric Power Production

Through humble beginnings, the first ever hydroelectric power station in Iceland began its operations in Hafnarfjörður in 1904. The station's energy output was that of 9kW, which, at the time, was enough to light about sixteen houses.

Over the next century, the country saw a surge in the practice, and today there exist approximately 37 large hydroelectric power plants in Iceland, along with about 200 smaller ones.

The largest of these plants, by a milestone, is the controversial Kárahnjúkar, with an energy output of 690MW. In comparison, the collective output from the other four largest plants comes to a total of 750MW. That means Kárahnjúkar generates more energy than its three biggest counterparts combined.

What’s more, Icelanders produce more energy per capita than any other nation in the world, or 53,832 kWh per person annually. Norway takes the place of the runner-up with less than half of that, which is an annual output of 23,000 kWh per person. To put these numbers in perspective, the average household of each resident in Iceland requires anything between 3,000 to 10,000 kWh of energy a year.

- See also: Iceland's Troubled Environment

Since the Icelandic people get the majority of their power from geothermal sources, and the nation's energy needs have been greatly surpassed for several decades, where is all this surplus of hydropower going?

Heavy Industry in Iceland

A little over a century ago, the people of Iceland made use of imported coal and kerosene to heat their homes, enabling them to survive the cold winters and harsh conditions at hand. While geothermal heat has, since settlement, been utilised directly for bathing and washing in natural hot springs, it was not until the dawn of the 20th Century that this power began to be harnessed.

In the 1920s and 30s, local authorities started establishing and promoting geothermal heating nationwide. Around the same time, the harnessing of the tremendous hydropower at hand also started to take flight, available due to the country's many powerful glacial rivers and inspired by similar actions in Norway.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Ásgeir Eggertsson. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Ásgeir Eggertsson. No edits made.

At the time, large industrial firms had started to build massive hydropower stations around Norway to power the likes of fertilizer factories. Their proprietors, in turn, paid good money for the power and thus the idea immediately excited the businessmen of Iceland.

Through the organised governmental development of power production, by the 1950s, Iceland had already exceeded its energy output beyond what was necessary for the nation. This, however, created a market for surplus energy―one that would be nonexistent without the arrival of heavy industry.

And so the scarcely inhabited country saw the rise of Áburðarverksmiðjan í Gufunesi (Gufunes Fertilizer Factory) in 1954 and Sementverksmiðja ríkisins (State Cement Factory) in 1958. Both plants were fueled by new hydroelectric power stations, but while their energy is indeed 'green,' that green holds a dark shade.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Christoph Hess. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Christoph Hess. No edits made.

Despite the issue of the land and river systems sacrificed for hydroelectric power stations, the industrial factories that constitute as the need for this power have, from the very beginning, been greatly criticised for chemical pollution and hazardous operations.

A pressing example is the burning of coal since, unbeknownst to many, Iceland currently burns over 160,000 tonnes of coal annually—set for a 60% increase in the next three years. While local homes have not been heated in such a manner since before World War II, the factories belonging to heavy industry make great use of the notoriously unsustainable energy source.

Another problematic aspect concerns what is going on within the plants themselves, although such information has often been difficult to reveal. The very forerunner of heavy industry in Iceland is the Gufunes Fertiliser Factory. Today, the plant has been shut down, but the greater operation consisted of five different units that each respectively produced hydrogen, nitrogen, ammonia, acid and carburetion.

Apparently, a lot can go wrong when dealing with such perilous chemicals. In 1990, a fire took place in the ammonia factory, prompting the Reykjavík City Council to demand a shut-down of the plant. The operations continued, and in 2001, there was an accidental explosion which generated a shock wave so powerful that it was felt by adjacent neighbourhoods. Many deemed the units to be unsafe and much too close to residential areas.

In 2010, the Supreme Court of Iceland ruled in favour of a woman who had sued the Gufunes operation because of bodily harm and induced disability. The woman had for 12 years been seeking justice, ever since the acid factory unit released 510 kg of ammonia into the atmosphere in 1998 without any warning to nearby residents.

As a result of being exposed to the poisonous fumes, the woman experienced severe health problems, so the Supreme Court eventually ordered the factory to pay her 4.2 million ISK in compensation. So what of the factory's successors? Surely, later operations must boast safer regulations, adhere to environmental standards, or at least not be located in the midst of a community.

Another two factories are currently located in West Iceland's Hvalfjörður fjord in Faxaflói Bay. Their area is named Grundartangi, after a spit in the fjord that's now gone under a landfill. The ferrosilicon plant belongs to Elkem Ísland and began operating in 1979, while the Norðurál smelter of Century Aluminum started performing in 1998.

Furthermore, in 2018, Silicor Materials are set to open a new silicon factory in the same fjord. With two other plants already operating in the area, sulphur dioxide, fluoride and particle pollution have all been reported over the years, while nearby farmers have reported a colossal loss of horses due to fluoride contamination in their pastures.

Meanwhile, The Icelandic Food and Veterinary Authority (MAST) long refused to reevaluate their examinations of toxins in the area, claiming the animals’ illnesses to be the result of overfeeding and poor care, as opposed to the churning industrial factory across the bay. The truth finally got revealed after a decade of battling the system, when experts from the University of Iceland and the veterinarian profession were allowed to examine the state of the horses and their pasturing better.

The Icelandic Planning Committee (Skipulagsnefnd) had, in 2014, vetoed the new Silicor Materials plant from facing environmental evaluations, but in June 2017, the District Courts of Iceland overruled that decision after a civil lawsuit. The suit was largely conducted by the Hvalfjörður Environmental Watch, who criticised the factories having superfluous control over their own evaluations.

Moving from the rural farmlands of Hvalfjörður to South Iceland's capital region: an aluminium smelter called Straumsvík, belonging to Rio Tinto Alcan, has stood on the edge of port town Hafnarfjörður since 1969.

Both sulphur and heavy metals have been measured in great quantities in the moss surrounding the plant, and according to Sigurður H. Magnússon, a researcher at the Icelandic Institute of Natural History, the levels of pollution equate the most highly polluted areas of Eastern Europe.

Close to Keflavík International Airport on the Reykjanes Peninsula, the inhabitants of Reykjanesbær are loudly objecting the operations of a silicon factory in Helguvík, with repeated proclamations of toxic fumes hazardous to their health. The plant began its operations only in 2016, but from the get-go, residents have reported foul smells in the air and a rise in visible particle pollution, as well as difficulties breathing and symptoms of chemical burns.

Measurements conducted in the area at first reported all particle contamination from the plant to be well within suggested safety limits. Later, however, under pressure from the residents, these numbers were deemed faulty upon reevaluation, with levels of arsenic in the air surpassing the standards of Iceland’s Environment Agency (Umhverfisstofnun) twenty times over.

After some additional evaluations, the Environment Agency made several serious demands of the factory's operations, with costs estimated at around 25 million Euros for repairs that would take approximately two years. As of the beginning of 2018, the factory has declared bankruptcy and retired its employees. But after the fertiliser factory incident at Gufunes, why was a chemical plant again constructed in the middle of a community?

Stakes are High, Morals low

The departure of the American Army Forces from Reykjanesbær in 2007, as well as monopolising endorsements of the area’s fishing quotas, emptied the town’s vaults and left it in a state of unemployment greater than anywhere else in the country. A similar tale can be told of the Hvalfjörður residents by the Grundartangi plants, where unemployment was a pressing issue and industrial workers were lacking jobs.

But with factories ejecting toxins less than two kilometres from livestock, humans and homes, can it really be said that the operations are for the benefit of the people, let alone the environment?

A matter of heated debate has been the silicon produced by these factories. Is it actually being produced for the construction of solar panels? To investors and politicians, such a claim creates a win-win situation; they can pretend to maintain Iceland's green reputation, while still making a handsome buck from foreign industrial operations.

Furthermore, major shareholders—including foreign investors, local pension funds and Arion Bank—have entrusted millions in the plants and don’t care to lose their investments. Although the silicon factory at Helguvík has shut down, a statement from Arion Bank proclaims they are looking for a new holder to continue the factory's operations―after 'necessary renovations' are made.

The man wasn't jesting. A press release from the Icelandic National Energy Authority (Orkustofnun) recently revealed eight new hydroelectric power plants to start construction in the next couple of years. Not much has been revealed as to what their power is for, prompting most to assume it means further arrivals of heavy industrial operations.

The National Planning Agency in Iceland has reviewed at least three of the projects already in motion as having decidedly negative effects on landscape, nature and wildlife. Their reports, however, also state that these effects are not sufficient for halting the construction of the plants, as valuations tell of bettered energy provisions for residents.

Since we have already covered the great amounts of surplus energy produced in Iceland over the last sixty years, is this any reasoning to be bought? At the very least, it is an idea that is sold, time and again, to rural residents whose powerlines have yet to be properly updated.

The Future of Iceland's Rivers

When construction of the Kárahnjúkar plant was taking place, supporters of the project often stressed that Iceland boasted an abundance of powerful rivers. With eight new plants on the horizon and hundreds of plants already operating, one has to wonder if this supposed abundance is, in fact, bottomless.

Þjórsá in South Iceland is the longest river in the country. With its source in Hofsjökull Glacier, it cascades through narrow gorges in the Highlands, with Tungnaá River flowing into it by the lowlands. According to Landsvirkjun, three new power plants are to be constructed along this very river.

One of these is the hydropower plant Hvammsvirkjun, set to dam Þjórsá six kilometers above Þjórsárdalur Valley, which will, in turn, be largely flooded by the new reservoir, Hagalón.

In 2015, thirty-eight farmers living by the banks of this river co-signed a statement against the plants, released in an issue of the country paper, Bændablaðið. One of the many problems the statement pointed out, is that several active volcanoes are situated by the river's source, including Hekla and Bárðarbunga.

If and when an eruption takes place, earthquakes will follow, meaning the dams could break and damage the environment further. Moreover, the valley itself has long been studied by archaeologists, with many believing it to conceal entire towns that disappeared when Hekla erupted in the Middle Ages. In his writings, Danish archaeologist Daniel Bruun even called Þjórsárdalur Valley "The Pompei of Iceland".

- See also: The History of Iceland

When it comes to irreversible landscape cultivation of the country's natural resources, the possibility of natural disasters are all but ignored, showcasing a short-sighted frame of mind based on immediate economic profits.

Preparations and construction have, as well, already started at Brúárvirkjun Plant, which will dam the upper banks of Tungufljót River in Southwest Iceland.

According to the National Planning Agency's report, the dam will wipe out over 24,000 acres of woodland and 17,000 acres of swampland, both of which are explicitly protected by Icelandic law unless their cultivation is deemed to be of pressing necessity.

Another plant, Hrafnárvirkjun, is to be constructed in Svartá River in Bárðadalur Valley in North Iceland. The Icelandic Master Plan for Nature Protection and Energy Utilization (Rammaáætlun) is currently fighting for the river's protection, but a statement from SSB (the energy company leading the project) reveals they don't worry these conversations to disrupt their plans in any way.

We must urge you not to skip viewing the video below, where the late Guðmundur Páll Ólafsson, a life-long advocate of Iceland's environmental cause, exemplifies upcoming events in a simple yet powerful manner. One by one, he tears out the pages of a picture book showing the Icelandic Highlands, until less than a dozen remain.

Despite what advocates of heavy industry would like you to believe, Iceland does not boast endless land for cultivation. The targets of power production are the geothermal areas lining the continental boundaries and the river systems that dot the Highlands. These are getting more scarce come every new construction, and if we continue down this path, soon there will be very little left.

In the Icelandic documentary Dreamland, local farmer Sæþór Gunnsteinsson stated how if we don't stop these operations now, we are not going to stop ten years from now. It's been nearly a decade since the film's release as we realise his words to ring true.

The work, based on the award-winning book by presidential candidate Andri Snær Magnason, criticises how the local government has actively attracted international aluminium companies to Iceland with promises of the cheapest energy in the world.

Sure enough, once the floodgates to the heavy industrialisation of Iceland were opened, there is hardly a power plant that finishes construction before another is in the works. It didn't stop with Kárahnjúkar, and unless preventive actions are taken, it will only go on.

In truth, this fight has been going on for a long time. At the beginning of the 20th Century, plans were in motion to harness the energy of Gullfoss—Iceland's most celebrated waterfall and the prime attraction of the Golden Circle route. The natural marvel was bought and sold between local and foreign parties until finally protected by the state in 1979.

- See also: Waterfalls in Iceland

Today, the story of the waterfall's salvation is greatly romanticised, where a woman by the name of Sigríður Tómasdóttir threatened to throw herself down the falls for their protection. Although Sigríður is rightly lauded as Iceland's first environmental campaigner, her protest was far from being the deciding factor in the eventual protection of the falls.

In reality, it was an extremely close call for Gullfoss. For decades, it was on the verge of being dammed, and operations were only halted due to a lot of bureaucratic back-and-forth between landowners and investors. Since then, the story of Gullfoss and Sigríður has served as an exemplar of Iceland's supposed excellency when it comes to promoting green values and nature preservation.

In reality, people in power have been dead set on promoting heavy industry in Iceland since the 1970s, but it was the 2008 financial crisis that set these plans in motion on a grand scale. While oppositions keep fighting for just evaluations of destructive effects, these projects keep multiplying and moving forward at an alarming rate.

The hydroelectric power plants of Iceland and their reservoirs repeatedly escape assessments for environmental impact―as well as the factories of heavy industry that utilize this power―making each estimate a lengthy fight against powerful corporations.

By going through with grandiose plans of power development in Iceland, we are sacrificing nature for what we deem is progress. But even if we'd believe this supposed progress to be worth surrendering our nature for, what are the suggested benefits, if any?

The Case of Economics & Alternative Industries

There exist much-repeated statements, based on economics, which seek to justify the massive industrialisation of Iceland’s natural resources. As a short-term solution, these projects are to create jobs and kickstart the economy. As a long-term solution, heavy industry should strengthen both the local economy and the Icelandic Króna.

But as an investigative episode of the local news programme, Kastljós, revealed back in 2013, the two largest aluminium companies utilising Iceland’s energy, Alcoa and Norðurál, pay little to no income taxes to the local economy. How these companies go about this is a known method of money-saving amongst international businesses, but Icelandic legislations make these tax-cuts even easier to achieve.

The way this works is that Alcoa and Norðurál are owned by larger sister companies in Luxembourg and Delaware, which are in turn owned by even larger international parent companies. The funds go from top to bottom, meaning debts of hundreds of billions gather at the bottom of the barrel.

This enables the companies to earn credit from each other, or, more correctly, from themselves, which excludes them from having to pay the taxes conducted by the Icelandic government. According to Kastljós, by the time of their enquires in 2013, Alcoa had not paid a single crown in income tax for a whole decade, while Norðurál had put forth just about three years’ worth after sixteen years of operating.

As for the upcoming Silicor Materials factory in Grundartangi, the company was not only vetoed from facing environmental evaluations but was, in 2016, awarded a tax discount of 4.6 billion ISK, as well as half-priced insurance fees and property taxes. This is money-laundering by definition, and it happens time and again, with these examples counting as the mere uncovered tip of the iceberg.

While it rings true that the plants offer jobs to residents, the number of jobs don't measure any higher than in other local industries. More workers are needed to construct the plants than to operate them, but foreign workers were, for instance, imported to build the Kárahnjúkar Hydropower Plant.

The reason given is one lauded with irony in light of our discussion. It was the protection of the Icelandic economy—since such a surge in the local job market would cause a negative inflation.

There are, in fact, other ways for this country to utilise its natural resources and create local jobs. Since 2010, Iceland has witnessed an astonishing surge in one of its markets, and since you are a visitor to this domain, you are most likely a part of it. The industry in question is tourism.

- See also: How to Find A Job in Iceland.

As of 2016, this particular industry has been estimated to contribute approximately 10% to the local GDP and is furthermore responsible for nearly 30% of Iceland’s export revenue. According to a report from Isavia, the annual increase of jobs only at Keflavík International Airport would measure up to one aluminium factory being constructed each year.

Not long ago, tourist services in Iceland embodied only a very insignificant part of the local economy. Then, just after the economic crash, the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull happened.

Suddenly, Iceland was on everybody’s lips. The opportunity was seized immediately by those who knew to promote Iceland as a sought-after travel destination, filled with unique natural wonders.

Iceland's economic recovery after the crash is credited almost entirely to the boom in tourism—not heavy industry whose profits have yet to emerge—with the number of people working within travel services today representing nearly 12% of the local workforce.

By preserving the unspoilt landscapes of Iceland, allowing its rivers to run free and maintaining what makes the country so attractive, tourism can continue to prosper and grow.

While heavy industry always apprehends vast areas of land and pollutes, travel services, when done right, can constitute a movement that is both green and sustainable. By protecting the nature that the people are here to see, the country sees a profit that is not only economical—but environmental and cultural as well.

With that said, greed and capitalisation can yet again spoil the chance for positive growth. The surge in tourism not only happened, it happened fast, and perhaps the country wasn’t quite ready to welcome visitors that, each year, outnumber its residents many times over. Mass tourism is a danger that lurks on the horizon, where nature is packaged and sold to the highest bidder.

Sustainable tourism, however, offers a desirable alternative, where the protection of ecological sites is ensured and local communities are guaranteed direct profits regarding economic relief. With the help of visitors that are aware of their impact, organised infrastructure and environmental preservation can, and will, surpass the supposed merits of heavy industry.

We at Guide to Iceland would like to seize this opportunity to thank you for being a part of this incredibly available solution. By respecting the nature you are here to see, you can contribute to the history of a public that, despite their mistakes, holds the environment dear and bears deep connections to their land and rivers.

What Can be Done?

As has previously been stated, this fight has been going on for a long time. It is therefore imperative to seek out the truth. Do not buy into greenwashed statements made in the media from spokespeople of industrial factories and power plants with blind faith, since these are well rehearsed in the knowledge of what environmental values people wish to hear.

The previous cases mentioned describe insistent requests for evaluations, and while there have been victories, those are not handed out on a silver platter, but fiercely fought for each time around.

Of course, you can join this fight right now. Many people in Iceland have made it their life’s work to protect what’s left of our nature against the further arrival of smelters, reservoirs, plants and factories. One Reykjavík-based non-governmental organisation that focuses on nature conservation is Landvernd, or the Icelandic Environment Association, founded in 1969.

The organisation is currently campaigning for turning the Central Highlands of Iceland into a National Park, which would significantly hinder hasty decisions made at the expense of the environment, such as the ones following the economic crash. The Icelandic people have already spoken, since a Gallup poll recently revealed that over 60% of them approve of such a project, in a result that exemplifies a nation that has finally had enough of excessive wildland cultivation.

- See also: National Parks in Iceland.

Being a nation of only 340,000 people, Iceland could greatly benefit from its voluminous amount of visitors, in the form of international contribution guided by environmental awareness. Following are several links where you can support the opposition of further grand-scale power developments in Iceland:

When visiting, engage in prior research on the local culture and environment, as to lessen your chances of making mistakes when traversing through the country and its nature. The contributions available are endless; avoid excessive consumption, refrain from littering, stay within designated road systems while driving and avoid treading off hiking trails, just to name a few.

- See more: Sustainable Tourism in Iceland.

You can also heighten tourism's contribution to the economy by actively shopping at local businesses and establishments throughout your stay. Remember that by coming here, you are directly taking part in supporting an industry that is capable of both satisfying the country's economic needs, and helping the preservation of its unparalleled and delicate natural sceneries.

With the way things are developing, it is not enough to arrive to Iceland's shores willfully thinking that our nature is unspoilt and our energy sources bountiful. Remember that knowledge is power.

All countries need energy, but Iceland in no way needs the great surplus energy meant for its corporations as opposed to its people. Heavy industry has long since overstayed its welcome in Iceland.

All countries need energy, but Iceland in no way needs the great surplus energy meant for its corporations as opposed to its people. Heavy industry has long since overstayed its welcome in Iceland.

What is your take on the power developments in Iceland? Do you think sustainable tourism is the ideal solution? Leave your thoughts and enquires in the comments box below.