Where does Iceland stand on the world’s political stage? How much influence does Iceland hold over its international counterparts, and what is the future of Iceland’s international cooperation? Read on to find out all you need to know about Foreign Relations in Iceland.

- Read about The Icelandic Flag

- Travel the country with this 7 Day Summer Circle Guided Tour

- Partake in this excellent 5 Day Self Drive Tour

The Republic of Iceland, a country of little more than 330,000 people, is, as it stands today, a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), the European Economic Area (EEA), the European Council, the United Nations and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), to name but a handful of international bodies.

Why You Can Trust Our Content

Guide to Iceland is the most trusted travel platform in Iceland, helping millions of visitors each year. All our content is written and reviewed by local experts who are deeply familiar with Iceland. You can count on us for accurate, up-to-date, and trustworthy travel advice.

Physically isolated from the neighbouring landmasses of North America, mainland Europe and Greenland, Iceland has, over the preceding centuries, nurtured a unique culture, language and outlook, further differentiating it from the closely-tied, ideologically similar states of Scandinavia and the like.

Even so, Iceland's history is deeply intertwined with the medieval kingdoms of Norway and Denmark. It has, after all, been under the control of both at intermittent periods. The 20th century saw this small democracy take its rightful position as an independent nation.

With the war's end came a flurry of new opportunities, new relationships and new challenges, all of which now rested solely in the hands of the Icelandic people. But how would they fare with their neighbours? And what of those warm and exotic destinations found halfway across the world? What would they make of this small, yet proud new nation?

A Little Back Story

To understand the foreign policies of modern Iceland, it is first crucial to gain an understanding of who Icelanders are, where they came from, and where they see themselves going. And so, a brief history is in order; for a more in-depth study of Iceland’s fascinating past, you can read The History of Iceland here.

First, Iceland was settled in approximately 870 AD by Norse settlers, many of whom were fleeing the tyranny of King Harald’s Norway. What they found was a land of birchwood and plentiful fishing, ripe for settlement. And so it was that Ingólfur Arnarson and his wife, Hallveig Fróðadóttr became known as this country's first settlers and the founders of its capital.

- Read Also: Where Did Icelanders Come From?

To make a long story short, Iceland was first an independent state, the Old Commonwealth, during which time it adopted Christianity, formed a parliament and began to log their history into the sagas. It was during this early period that the first seedlings of Icelandic national identity were born.

After a brief civil war, Iceland would fall into the hands of Norway, something made possible through the Old Covenant (1262–1264). It later became a subject of the Scandinavian alliance, the Kalmar Union (1397–1523), before its dissolution, at which point Iceland became a subject of Denmark.

Despite this tumultuous power game, Icelanders felt little loyalty to their overbears, instead deciding to nurture a strong independent spirit. During the First World War, Icelanders contended with one another that such events were little more than “Europeans fighting again”.

It was an economic opportunity readily exploited, particularly in the mass export of wool, an opportunity that arose thanks to three main factors; the destruction of Europe’s grazing lands, the neutrality of sovereign Denmark and the lack of military capability back home.

- Read Also: Vikings and Norse Gods in Iceland.

Even so, the war was considered by most Icelanders as a “killing game”, to borrow the words of the MP and lawyer, Skúli Thoroddsen, despite the fact that approximately 1200 Icelandic Canadians did take up arms during the conflict.

The First World War also saw Iceland suffer terrible debt, a drop in living standards and further isolation from its neighbours. By 1918, the point had seemingly been proven; though a physical separation may exist, Icelanders were still interconnected to the actions and whims of those elsewhere, readily feeling the consequences of a war fought one and a half thousand miles away.

Any thoughts of longstanding peace the Icelanders might have fostered were soon tarnished. The Second World War would see a far greater impact; not only was the country preemptively invaded by the Allies, dead set on denying Iceland to the Germans, but it soon felt the tangible effects of outside influence, leading to a duality in Icelandic culture that still exists today.

- Read Also: A History of Reykjavik.

By the end of the war, in 1944, Iceland would see itself transform from a sovereign state of Denmark to an independent republic, setting its own national priorities and directing its own affairs.

Icelanders Abroad

Around the world, there are significant populations of Icelanders living in communities, almost all of which are descended from periods of mass emigration from the country.

- Read Also: What is an Icelander?

The first of these occurred in the late 19th Century, partly as a result of the 1783 Laki volcanic eruption; the noxious fumes killed off approximately 80% of Icelandic livestock, and a quarter of the country’s population would perish with the ensuing famine. This, naturally, made Iceland a difficult place to live, and much of the surviving population was looking for any possible route off the island.

Though numbers are tricky to pin down, given Denmark’s dominion over the country at the time, it is estimated that approximately 10,000 to 25,000 Icelanders emigrated, travelling the Great Lake states of North America, such as Wisconsin and Dakota, as well as regions in Canada.

It is widely agreed that Icelandic emigration to Canada outmatched that to the United States because the migratory trends began later from Iceland than elsewhere in Scandinavia. There was also a Canadian travel agent already stationed in Iceland during this period encouraging Icelanders to move for a better life elsewhere.

Upon arrival, the Icelanders found their countrymen lacking in numbers, and so routinely took up employment and shelter with other immigrants from Norway or Denmark.

As the numbers of Icelanders in North America grew, so too did the communities that went with them; according to a census taken at the dawn of the millennium, over 42,000 American citizens claimed that they were descended from Icelandic immigrant families and felt a sense of pride because of their Icelandic identity.

Believe it or not, there is also a small community of Icelandic Brazilians, the descendants of roughly forty Icelandic who emigrated to South America at the end of the 19th century.

Iceland and Scandinavia

Photo by Ange Loron

Photo by Ange Loron

Iceland’s closest ties are, quite naturally, with Scandinavia, comprised of Sweden, Norway and Denmark, having been first settled by adventurers derived from these three nations. Thus, Icelanders are directly descended from their Scandinavian cousins, boasting the same blonde locks, blue-eyes and rosy-cheeked complexion.

- Read Also: Ultimate Guide to Flights to Iceland.

The Icelandic language stems from Old Norse and is largely unchanged from ancient times, making the dialect incredibly unique, even in the Scandinavian realm.

Contemporary Icelanders are still able to fluently read and understand the ancient sagas, written over a half a millennia ago, and have thus been able to easily translate almost all of our current knowledge about Norse Mythology and ancient life in the country.

Historically, Iceland has been under the dominion of both Norway and Denmark over different periods, and as such, were obligated to follow the legislation of each respective kingdom, trading freely, paying taxes and abiding by the cultural and ecclesiastical norms of the time.

Photo by Jacek Dylag

Photo by Jacek Dylag

This caused much internal strife throughout Iceland’s history, with many factions staying loyal to their overseas King, while other clans felt that domestic power should lie in the hands of those who lived permanently on the island.

The Nordic House in Iceland’s capital city, Reykjavík, is perhaps the best location to learn more about Iceland’s strong ties to Scandinavia; the establishment displays authentic artwork, boasts a dedicated library and serves authentically Scandinavian cuisine, perfect for those travellers looking to come to grips with this country’s fascinating and eclectic culture.

Iceland and the United States of America

Photo by Kyle Mills

Photo by Kyle Mills

Icelanders have long maintained a relationship with the United States of America, with some claiming that it goes as far back as Leif Eriksson’s voyage to the New World, where it is said he established an ultimately doomed settlement in Vinland (Newfoundland, Canada). This was thought to have occurred 999 AD, many years before Christopher Columbus, the first “official” European to discover America.

The United States first became interested in Iceland during the 1880s; it was proposed to Congress that the island should be bought from Denmark, though this was ultimately crushed in favour of more isolationist policies. Instead, Iceland was left to its own devices, though the US would set up early trade between the two countries.

The next time the US took a formal interest in Iceland was during the Second World War—both the Allies and the Axis powers knew of Iceland’s strategic geographical importance and so it was quickly decided that the island be preemptively invaded in order to deny it to the Germans. This was undertaken peacefully by the British in 1940 before power was handed over to the Americans a year later.

During this period, the US built roads, hospitals, airports and infrastructure that greatly facilitated Iceland’s development into a modern western democracy.

At the end of the war, Iceland and the US signed the Keflavik Agreement, a document outlining the United States' obligations to Iceland, as well as its propositions. It was decided that the US would militarily defend Iceland in the case of war, as well as maintain a permanent base on the Reykjanes Peninsula.

Throughout the next thirty years, the presence of Naval Air Station Keflavik was a hot topic among the Icelandic population; some were grateful for its presence, while others felt the Americans were secretly planning to store atomic bombs on the station.

Still, this longstanding presence had an undoubtable effect, and as the Americans began to integrate more and more with Icelandic society, the greater the dilution became. In 2018, the influence of the United States is around almost every urban corner in Iceland.

Be it this population's collective love of hot dogs, cinema, hip-hop, rock ‘n roll and flashy cars, or the typical allure of capitalism, Icelanders can trace many of their national preferences to the Americans.

Iceland and Poland

Photo by Kamil Gliwiński

Photo by Kamil Gliwiński

Diplomatic relations between the Republic of Poland and Iceland began formally in 1946, though the countries were at least aware of each other as far back as 1658; this was the year that Czech monk, Daniel Strejc-Vetterus, published a Polish travelogue of his time in Iceland. In the 19th century, the then Polish secretary to Napoleon, Edmund Chojecki, also spent time here.

In 1924, Iceland and Poland signed a Treaty of Commerce and Navigation and, in July 1945, recognised the Polish Provisional Government of National Unity. The Polish Consulate was opened in Reykjavik in 1956, closing in 1981. Today, both countries maintain an embassy in one another's territory.

Today, there is a tight-knit community of Polish citizens living in Iceland, approximately 14,000, the vast majority of whom have moved here for the employment opportunities in the shipyards during the 1960s.

This steadily increased for the next twenty years, with the 1980s seeing moves by the Icelandic government to officially recognise Polish workers as part of the Icelandic state. By the mid-2000s, the Polish population in Iceland exceeded 20,000, though almost dropped by half after the 2008 Financial Crisis.

- Read Also: What to Pack for Travel in Iceland.

The exact number is difficult to verify as Polish people need neither an employment or residency permit to live and work in Iceland. This is a result of Iceland’s 2006 construction boom and the necessity of outside labour that came with it, as well as changes to Poland’s membership in the Schengen Agreement, made in 2007.

Throughout history, there have been a number of migratory movements from Poland to Iceland, the first of which took place in the 19th Century. Polish migration was halted during the Cold War, given the enormous restriction of movement placed on those living in communist Poland, then reestablished itself after the fall of communism in 1989.

Photo by Lucas Albuquerque

Photo by Lucas Albuquerque

Interestingly enough, a census taken in 2012 found that Polish immigrants to Iceland tended to find English a practical language to use here, often learning it before learning Icelandic.

Though some have considered it a challenge assimilating Polish people into the Icelandic culture, they still make up the largest ethnic minority in the country, making up roughly 3% of the population, and 37% of all immigrants.

Iceland and Germany

Photo by Claudia Schwartz

Photo by Claudia Schwartz

Both Germany and Iceland are members of NATO, and hold respective embassies in one another’s capital. Since the establishment of diplomatic relations, Germany has gone on to become one of Iceland’s key trading partners, importing transportation and machinery and exporting aluminium and fish.

The culture of Iceland is particularly well looked upon in German, who culturally share much of the same genealogical heritage with the Icelandic people. Of particular gravitas is Iceland’s literature and music scene. In 2011, Iceland served as the guest of honour at the Frankfurt Book Fair.

In regards to tourism, Germany is leading the way when it comes to overnight stops and stays in guesthouses and hotels. Approximately 40,000 Germans visit Iceland each year, with that number seen to be increasing, proving the country’s relevance to Iceland’s all-too-important tourism industry.

The Germans are also particularly known for their love and proficiency in scuba diving as well as interest in Iceland's horses. Given that Silfra Fissure has often been cited as one of the top 10 scuba diving sites in the world, it is no wonder that so many German visitors travel to Iceland each year to experience the delights and challenges of drysuit diving in the near-freezing glacial water.

And Germans are so fascinated by the Icelandic horse, that more than 50,000 Icelandic horses are currently living in Germany - but any Icelandic horse that's exported may never return to Iceland.

- Read Also: The Icelandic Horse | A Comprehensive Guide.

Iceland and Israel & Palestine

Photo by Sander Crombach

Photo by Sander Crombach

Iceland maintains diplomatic relationships with both the State of Israel (29th November 1947) and the State of Palestine (beginning 29th November 2011). Iceland voted in favour of the Partition of Palestine in 1947, leading to the formation of Israel. Icelanders first ever contact with Jerusalem, however, dates as far back as the 1400s, when Icelanders participated in the Crusades.

Since 1987, Iceland has had the non-governmental organisation The Iceland-Palestine Association (Félagið Ísland-Palestína) which works to represent, defend and "support the Palestinian struggle against occupation and refugees' right of return". In 1989, the values of the Iceland-Palestine Association, including both Israel’s right to exist and the right of Palestinian nationhood, were adopted as policies of the Icelandic government.

Iceland was the first Western country in the world to recognise Palestine as an independent nation, having passed legislation stating so on 29th November 2011. It should be noted that there were no votes in opposition, though a number of politicians did abstain. Iceland currently recognises the State of Palestine as stipulated by 1967 borders.

Photo by Toa Heftiba

Photo by Toa Heftiba

In 2015, Reykjavik City Council proposed to boycott Israeli goods coming into the country. The Icelandic government quickly put out a statement denouncing the boycott, assuring the State of Israel that this was not, in fact, the policy of their ministers—very much an “RTs are not endorsements” type affair. The decision was later retracted by the council.

Iceland and Great Britain

Photo by Luke Stackpoole

Photo by Luke Stackpoole

Approximately 850 kilometres away from the shores of Scotland, Iceland has, over the years, held a contentious relationship with the British. This is despite the fact that, for the most part, Icelanders and Brits have always found one another more than cordial, with individuals from both nations enjoying easy travel between them both.

- Read Also: Top 9 Most Famous Icelanders in History.

Naturally, this hasn’t stopped the British government from misbehaving every so often, as it is prone to do. In 1940, the Brits chose to ignore Iceland's protests of World War 2 neutrality, preemptively invading so as to deny Germany a strategic hold over the North Atlantic. Though there were protests, the invasion was more than peaceful—Icelanders even helped the Allied troops unload their ships.

Of course, there was also the blodless Cod Wars, the closest Iceland has ever come to a military skirmish. The Cod Wars, as well as the events leading up to them, are fascinating in themselves, but complicated, an almost 700-year history of tension caused by the British flagrantly fishing in Icelandic waters.

In a response to dwindling fish stocks, Iceland expanded its territorial fishing grounds 4 to 12 nautical miles (7.4 to 22.2 km) in 1958 to universal NATO opposition. The British responded as expected, by re-sending their fishing fleet to Iceland, only this time in the company of Royal Navy destroyers.

The Icelanders immediately responded with protests outside of the British embassy—British Ambassador, Andrew Gilchrist, gleefully taunted the crowds by playing bagpipe music through his gramophone—and quickly threatened to leave NATO should the dispute remain unresolved.

- Read Also: The Most Infamous Icelanders of History.

After a few decades of peace, stability and cooperation, tensions between Iceland and the UK would flare up once again. During the 2008-2011 Icelandic Financial Crisis, the British Government held Iceland to the same standards as international terrorists, a result of the Icelandic government’s refusal to fulfil Britain’s payment requests. This would become known as the Icesave Dispute and, quite potentially, was one of the most ludicrous chapters of the financial crisis.

Photo by Charles Postiaux

Photo by Charles Postiaux

When the British prime minister, Gordon Brown, defended the use of anti-terrorist legislation against Landsbanki bank, as well as the freezing of Icelandic assets in England (pardon the pun), Icelanders responded with an 80,000 strong petition entitled “Icelanders are NOT terrorists”. This was accompanied by a wide array of amusing pictures and spoof videos pointing out the hysterical nature of Britain's actions.

In January 2013, the dispute came to a conclusion after the EFTA Court cleared Iceland of all charges. Since then, Iceland's economy has made a swift recovery and relations have once again soothed.

- Read Also: Football in Iceland | The Secret to Success.

Arguably, the event that created the greatest tension between Iceland and the UK is the republic’s shocking 2-1 victory during the UEFA Euros 2016. Almost immediately, British tabloids shamed their home side with headlines reading “BEATEN BY A SUPERMARKET”, whilst Icelanders cheered “their boys”, treating them as national heroes upon returning to the country after being knocked out by France.

Iceland and France

January 10, 1946, saw diplomatic relations established for the first time between the Republic of Iceland and the French Republic. Today, both countries are members of NATO, the EEA and the United Nations.

Relations go back much further than the beginning of formal welcomes, however. French vessels were regularly visiting Iceland by the late 18th century to make the most of its bountiful fishing grounds.

Photo by Rafael Kellermann Streit

Photo by Rafael Kellermann Streit

- Read Also: 10 Reasons Icelanders are Proud of Iceland

The French organisation Société des hopitaux francais d'Islande built three hospitals in Iceland in the early 1900s, one of which currently stands in the East Iceland village of Fáskrúðsfjörður, having been rebuilt in 2014.

This town boasts an incredible French Connection, with a museum dedicated to the fishermen’s story and a beautifully maintained sailors graveyard. Each July, the village will celebrate its French heritage with a festival; this is repeated in the twinned-town of Gravelines in France, where two celebrations are held each year, one for the sailors’ departure and one for their return.

Currently, France and Iceland focus on four main areas of cooperation; expanding French-language services in Iceland, promoting artistic cooperation in the fields of cinema, music, dance and the visual arts, furthering scientific research and building relationships between universities in both respective countries.

Iceland and China

Photo by Kelly Tokas

Photo by Kelly Tokas

Diplomatic relations between the People's Republic of China and Iceland began on December 8, 1971. Once talks began, Iceland and China were quick to help one another achieve their goals; China stood in support of expanding Icelandic fishing territory, while Iceland proposed that China have its seat rightfully restored on the UN Council.

Since then, trade has increased year by year, with an ever-greater focus on business and cultural interaction. Not only has Iceland held numerous China Days in the past, but it has also taken an active role in China's art scene, sending over numerous local artists to exhibit their work. In response, the Chinese have sent a number of sports coach delegations to Iceland for training.

One of the greatest oddities concerning Iceland and China are their physical differences. Consider the sheer disparity in population size between the Republic of Iceland, approximately 335,000, and the People’s Republic of China, 1,415,045,928.

At a rough estimate, that means there are around 4222 times the number of people living in China then Iceland, a number that seems out of this world when you also stop to weigh up their respective land sizes and find you could fit a tidy 93 Iceland's inside of mainland China.

In 2013, Iceland became the first European country to sign a Free Trade pact with China, selling its expertise in geothermal energy after nearly six years of talks. Today, China maintains an embassy in Reykjavik, while Iceland maintains both an embassy in Beijing and an Honorary Consulate in Hong Kong.

Iceland and Japan

Photo by Jezael Melgoza

Photo by Jezael Melgoza

Formal diplomatic relations began with the State of Japan in 1956 and today, Iceland has an embassy based in Tokyo as well as three Honorary Consulates in Kyoto, Nagano-shi and Tokyo.

Students of the Japanese Language and Culture course at the University of Iceland have, for the last thirteen years, held a Japan Festival, jointly organised by the Japanese embassy. During the festival, visitors are soaked in Japanese culture, everything from manga comics to traditional tea ceremonies. There are also musical performances from established J-Pop bands, martial arts displays, arts and crafts and conferences providing further insight into the Japanese experience in Scandinavia.

As a part of the Japanese Language and Culture course, all students are required to go on a one year exchange program in Japan, and the teachers of the course all come from Japan.

Photo by Magic Mary

Photo by Magic Mary

Iceland and Japan share a common interest in continuing the practice of commercial whaling, much to the chagrin of the international community, which has largely argued for an all-around band since the seventies. The only other country aside from Iceland and Japan to continue commercial whale is Norway.

The Japanese also share another crucial factor about their environment with the Icelanders; both live on volcanic islands. Understanding this, the respective governments set out to cooperate in the field of risk reduction, both attending a conference in 2015 for further talks on extending their cooperation further.

There also exists The Scandinavia-Japan Sasakawa Foundation, an establishment that aims at a greater cultural interaction between Japan and the five Nordic nations. The Scandinavia-Japan Sasakawa Foundation offers scholarships to residents, institutions and organisations of both Japan and Scandinavia, mainly in the fields of Medicine, Science and the Humanities. Interested parties can investigate these scholarships and grants further here.

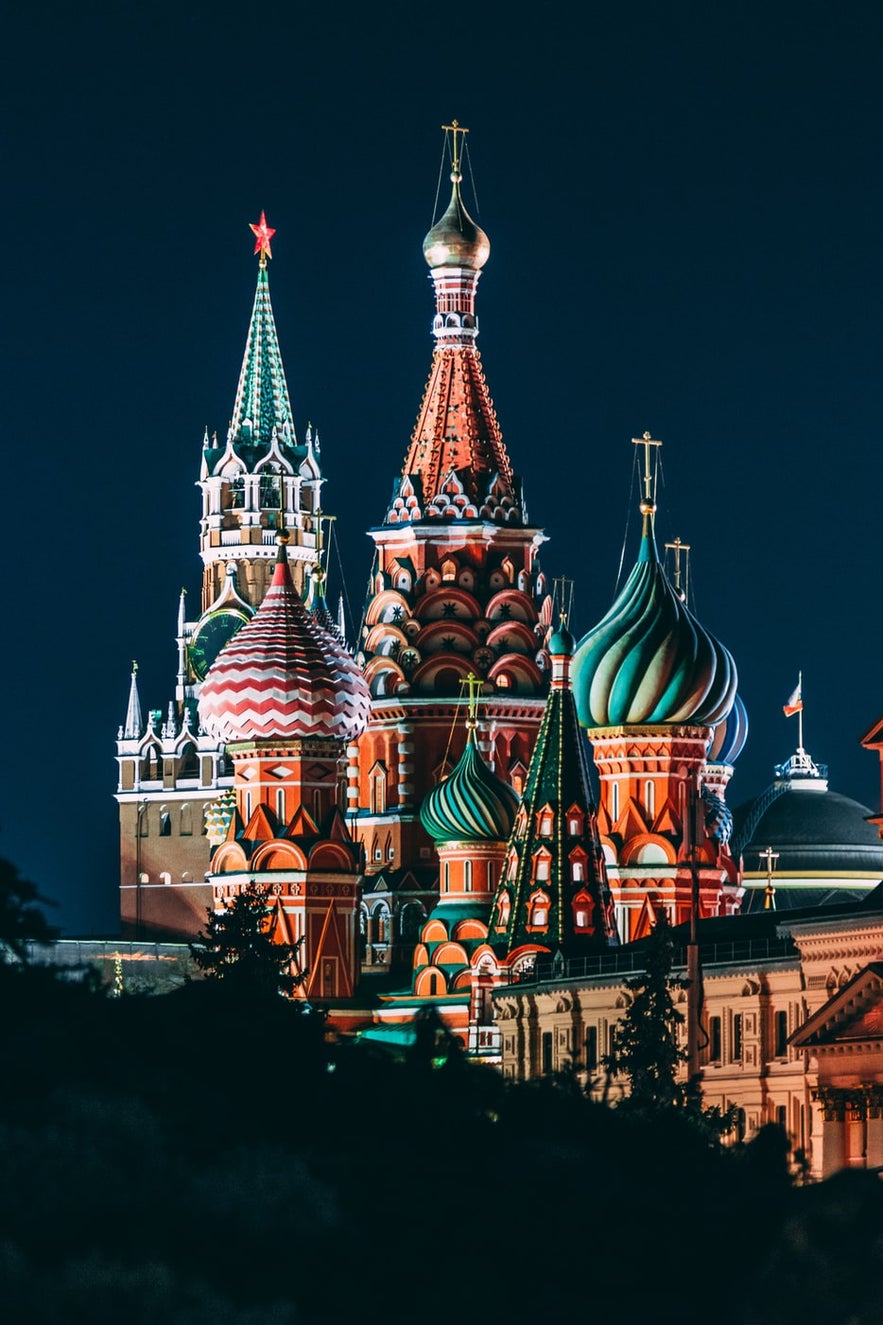

Iceland and the Russian Federation

Photo by Nikolay Vorobyev

Photo by Nikolay Vorobyev

Russia and Iceland first began diplomatic relations following the Second World War, quickly upgrading their missions in Moscow and Reykjavik to embassies in the 1950s. In the next two decades, Soviet expeditions did much to help further Icelandic scientific study; in 1973, the first geological map of Iceland was built, and a number of surveys were taken of Icelandic coastal waters.

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union actively bought Icelandic cod stocks, in large part to tend communist sympathies in the country. This started something of a market war, where the US hurriedly bought Icelandic cod in response, as well as persuading its allies such as Spain and Italy to also get in on the deal, hence weakening the Soviets’ position. This, of course, was a particularly fruitful time for the Icelandic economy.

Iceland also held the Reykjavík Summit in 1986, a meeting that took place in Höfði House between U.S. President Ronald Reagan and General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev. The aim of the meeting was to draw an end to nuclear armament and the Cold War, and though ultimately unsuccessful, the talks did lead to many fruitful steps that greatly de-esculated the situation.

- Read Also: Sustainable Tourism in Iceland.

During the banking crash of 2008-2011, Iceland was hurriedly seeking a cash injection after its traditional western allies refused to help save the crumbling economy. A delegation was sent to Russia, though this also proved to be unsuccessful. Iceland would later secure loans from Scandinavian countries, as well as the International Monetary Fund.

Today, Iceland and Russia work together in a number of key areas: inter-parliamentary cooperation, trade and economic relations, fishing cooperation, clean energy partnership and cultural interaction (i.e. Russian culture days in Iceland).

Iceland and the European Union

Iceland has never been a part of the European Union, though it is heavily integrated with the institution through its membership in the European Free Trade Association, European Economic Area and the Schengen Agreement, all of which overlap in regards to legislation and policy.

- Read Also: Where to Stay in Reykjavik

Photo by Guillaume Périgois

Photo by Guillaume Périgois

There are a number of good reasons for Iceland’s refusal to enter the European Union. Most importantly, membership would likely have an adverse effect on the Icelandic fishing industry, an inconceivable notion given the industry’s importance to Iceland’s livelihood.

Iceland also maintains strong ties with the United States, making its dependence on Europe far less pressing than one might at first realise. The Icelandic electoral system also favours rural communities in the country, which tend, by enlarge, to be more eurosceptic than urban voters.

- Read Also: Where to Stay in Iceland

Not only that, but Icelandic nationalism is a powerful force, especially given the country’s population size; Icelanders are more likely to study, work and travel to countries that hold eurosceptic ideals, such as the US, Scandinavia and the UK, making membership a controversial prospect.

As proof of that point, Iceland applied for membership in 2009, but the proposal was immediately shut down within the Icelandic government itself. Given Britain's imminent withdrawal from the European Union, many in the UK are looking to Iceland as a shining example of how an island nation can prosper outside of the institute's regulations.

Iceland and NATO

NATO (“North Atlantic Treaty Organisation”) was established on the 4th April 1949 with the express intention of dissuading and protecting against the spread of ideas originating from the communist Soviet Union.

Given that, at this time, Iceland had a significant portion of its population sympathetic to the communist movement, as well as a seemingly unending US military presence in the country, participation in NATO was controversial, to say the least.

Iceland was one of the founding signatories, benefiting enormously from one of the pacts main directives, that any attack on a member state would be considered an attack on the organisation itself, meaning that other member states were obligated to step in defensively. The reason why this is important is clear to see; Iceland has, aside from its Coast Guard, no standing military of its own.

- Read Also: Travel Etiquette in Iceland.

With that being said, Iceland has been known to participate in unilateral military operations abroad. As the below documentary, "The Chicken Commander", makes clear, Iceland has the Icelandic Crisis Response Unit (ICRU) (or Íslenska friðargæslan or "The Icelandic Peacekeeping Guard"), a routinely non-uniformed and non-armed branch made up of members of the National Police, Coast Guard, Emergency Services and Health-care system.

Iceland is referred to as NATO’s “Eye in the North”; it is, after all, the northernmost member state, and is thus able to actively monitor the activity of other nations, not just within its own territorial waters, but the Arctic also, an area that has over recent years become of interest to those superpowers looking to expand their energy resources.

Did you enjoy our article about the International Relations of Iceland? What surprised you about Iceland's place on the world stage? Make sure to leave your queries and thoughts in the Facebook's comments box below.