Akureyri, the Capital of North | Culture, History and Activities

What is the history of Iceland’s second-largest city and “Capital of the North”, Akureyri? How many people currently live there, and what attractions and activities can be found close by? How does Akureyri culture differentiate itself from its southern neighbour, Reykjavik? Read on to find out all you need to know about the city of Akureyri below.

Photo by Ludovic Charlet

- For more information, read Top 13 Things to Do in Akureyri

- Planning on visiting Iceland this year? See this Summer 7 Day Self Drive Tour

- If you're hoping to visit in winter, book Winter 7 Day Self Drive Tour

An Introduction to Akureyri

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Monster4711. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Monster4711. No edits made.

In general, visitors to Iceland roundly focus their attention on the capital city, Reykjavík, located only forty minutes from the country’s one international airport, Keflavík. This makes sense, after all, given that Reykjavík is the beating heart of Icelandic culture and society, boasting more hotels, restaurants, bars, tour opportunities and cultural landmarks than anywhere else in the country.

Many people, including Icelanders—particularly those cheeky 101 locals—are quick to jokingly claim there are no other major urban settlements in Iceland besides Reykjavík… quite willingly, many guests choose to accept this coy approach to humour, readily organising their holiday around the capital alone whilst quietly dismissing the quintessential charms of Iceland’s smaller settlements.

Whilst this is by no means a bad idea if you’re only visiting a few days, it does cut off an enormous chunk of the potential vacation experience for those planning to spend an extended period of time here.

For those with a week or two in Iceland, taking to the road is a must, with a wealth of natural attractions, cute fishing villages and awe-inspiring sights all waiting for those who venture out to unravel them. Among these, a crucial stop is what is colloquially called “Iceland's Capital of the North”, Akureyri, the island’s second-largest city.

In truth, calling Akureyri “Iceland’s second largest city” is something of a misdemeanour seemings as the population is only around 19,000 people. This would make the city more like a town if it were anywhere else in the world, but given that we’re in Iceland, the classification fits. What does size matter, eh?

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Thalion77. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Thalion77. No edits made.

Despite this small population, Akureyri boasts a fantastic culture all unto itself. The city is home to numerous museums, art exhibitions, designated green spaces and, of course, a local residence that shares much of the same passions and interests as Icelanders across the country.

- See Also: Sustainable Tourism in Iceland.

But how did Akureyri become the second go-to location in Iceland? What are the city’s origins, and what explains its patient growth over the last century? To uncover these secrets, we must first dip into the fascinating history of this young, yet vibrant city.

The History of Akureyri

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Oscar Wergeland. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Oscar Wergeland. No edits made.

As with almost all Icelandic history, we must look to the Ancient Sagas, (Icelandic: Íslendingasögur) for any real, contextual understanding. These rich, literary records are, without doubt, the greatest single source for revealing the nature of Icelanders, where they came from and what influences and events helped to shape their culture.

The sagas of the Icelanders are unrivalled in human civilisation for their scope, accuracy and archival value. They are, quite rightfully, one of the greatest points of pride for the Icelandic nation.

The Age of Settlement

From the Landnámabók, we know that the area’s ‘founding’ settler was an Irish Viking by the name of Helgi Magri Eyvindarson. Helgi’s story is a fascinating one; born to an Irish mother and a Norse father, Helgi had been sent to live southwest, in foster care as a child. When his parents went to retrieve him, they found the young boy so starved, they could barely recognise him. Thus, his nickname then on was “Helgi the Slim” or “Helgi the Lean”.

Helgi Magri Eyvindarson set out to Iceland with his wife, Thorunn Hyrna, in 890 AD, landing within Eyjafjörður. Exactly why it was that he did is still a mystery, though many have surmised that it may have been due to his unique blend of Christian and Norse faiths.

- See Also: The Most Infamous Icelanders of History.

There is no question that Helgi was a devout Christian, but upon taking to sea voyages, he was known to put his faith into Thor, the Norse God of Thunder. Whether this has any relevance as to his reasons for travelling to Iceland, we will likely never know for sure.

What is known, however, is that one of his daughters was named after the Norse deity, long after Helgi adopted the Christian faith. We also know that he chose his "landing spot" in Iceland in the traditional Norse manner, by throwing two wooden pillars overboard (these are said to have landed roughly 7 kilometres away from Akureyri's current location).

This mix of practices seems to imply that the Christianisation of Iceland was not as black-and-white as people tend to believe, but was often, in fact, operating under a strange union, comprised of two very different, ancient belief systems.

Helgi was said to have spent his first winter at Hámundarstaðir, far west of modern-day Akureyri, before setting out to fully discover the island’s northern regions. In time, Helgi had lit a number of fires between Siglunes and Reynisnes, signifying the ejection of evil spirits and the establishment of a codified estate. The sun, fire and heat were all thought to be weapons used against supernatural creatures. Trolls, elves and hidden folk have long been a part of the fabric of Icelandic society.

- See Also: Folklore in Iceland.

Given the sheer amount of land accumulated, Helgi’s estate would go on to be one of the biggest at that time. According to the sagas, his farmstead was named Kristna (Christ's Peninsula). He is then rightfully regarded as Akureyri’s founding father; he is to the north what Ingólfur Arnarson is to Iceland’s capital, Reykjavík.

Exactly when the name "Akureyri" began its popular usage, no one is exactly sure. And whilst a number of different theories exist attempting to justify the name, there is only one that is widely agreed upon; the city's name can be translated roughly to "Field Sand-spit," in likely reference to a sheltered cornfield that once existed in the area's narrow gullies.

The Growth of Akureyri

Permanent settlement did not begin in Akureyri until 1778, though the community is mentioned on a number of occasions before that. Take, for example, court documents dated to 1562 listing a woman from Akureyri convicted of adultery. According to these records, the woman was not in possession of a marriage license after being caught in bed with a young chap, something of a scandal given the time period.

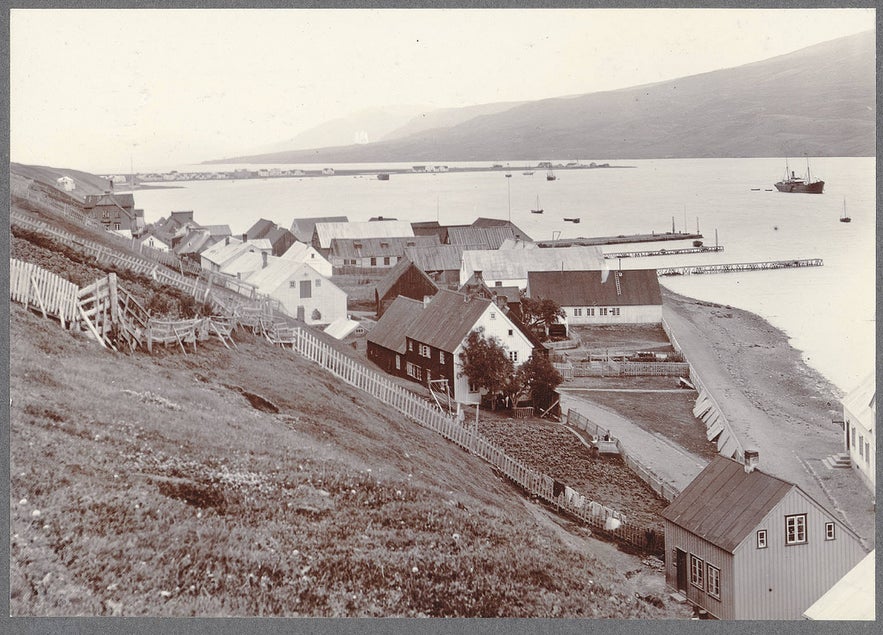

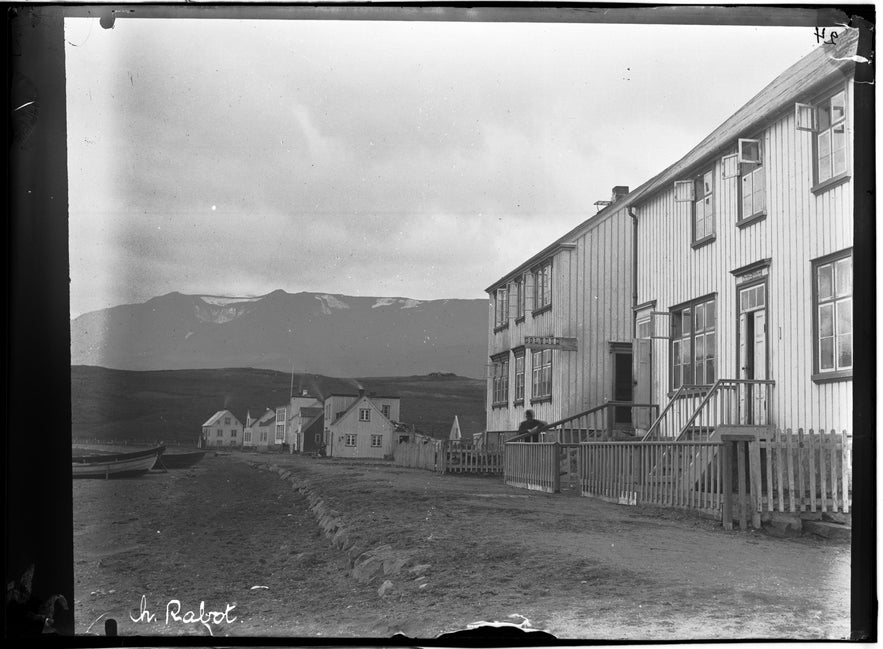

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Sigfús Eymundsson. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Sigfús Eymundsson. No edits made.

In the mid-16th century, the only buildings in Akureyri were shops and warehouses owned by transient Danish merchants. During that time, Iceland was an official territory of the Danish Monarchy, and Icelanders were subject to the crown. Whilst this did lead to conflicting attitudes, it undeniably aided the flow of trade, communication and technology across Iceland's many regions.

Akureyri was established as an official trading post in 1602. Unlike the natives, however, these merchants would not stay in the Akureyri area all year, returning home to their native Denmark each winter. This, naturally, was an obstacle to growth in the town, which is, perhaps, one of the major reasons as to why Akureyri took quite so long to prosper.

- See Also: Top 12 Things To Do In Iceland.

Throughout the following 200 years, Akureyri was largely utilised as a base camp for these trading Danes, in part thanks to the advantageous conditions of the settlement’s large, natural harbour. Even so, a sustainable life in Akureyri was still a while away; it would take a focused effort on developing the region's potential for agriculture before any tangible changes could be seen. The first house was built in 1778 after the Danish Merchants were permitted to reside in Akureyri over the winter.

Photo by Frederick W. W. Howell

Photo by Frederick W. W. Howell

- See Also: 10 Reasons Icelanders are Proud of Iceland.

By 1778, the then King of Denmark (and, by default, Iceland) had turned his attention to improving living conditions within his territories. Akureyri received its municipal charter in 1786, thus making it an officially recognised settlement.

Around this time, the Danish Merchants began to introduce farming techniques in order to maximise the region's fertile soil. By 1800, the Icelanders were successfully harvesting potato crops, something that had been seemingly impossible only a few years beforehand.

Unfortunately for the King’s intentions, Akureyri’s population growth came to a shattering halt at 12 people in the following years. The Danish Monarchy considered this a disappointing outcome, and so consequently revoked the settlement’s municipal charter in 1836.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by NVE. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by NVE. No edits made.

Once again, Akureyri was to be little more than an 'unofficial' outpost, that was until 1862 when the charter was reinstated. In other words, it seems Akureyri’s history can be characterised by those in power flip-flopping over whether the settlement had any real future potential.

From 1862, Akureyri's growth spurt truly began. Agriculture in the surrounding area helped to draw workers and their families, becoming an essential contributor to the economy alongside fishing, fish processing and trade.

- See Also: International Relations of Iceland.

The Eyjafjörður Co-operative Society, an assembly of local farmers and traders, became a driving force for growth in the town given their fierce negotiations with Danish Merchants. This made living and working in Akureyri more feasible for many people, especially considering that agricultural and fishing industries were on the rise. By 1900, the town's population was an impressive 1370 people.

Even so, this was early days in the Akureyri's development, and the lack of modern amenities, even by the standard of the day, would have made the settlement a challenging place to live.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Andrea Zanenga. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Andrea Zanenga. No edits made.

This is, perhaps, no better communicated than by the travel writer, Ethel Brilliana Tweedie, who travelled to Akureyri in 1888 with her brother, Vaughan Harley, future husband and two fellow Britons on the SS Camoens, a cargo and passenger ferry that routinely shipped between the UK and Iceland. Visiting Iceland was considered something of a robust, challenging and exotic thing to do in the later 19th Century, where the trend was more directed towards the likes of fashionable Vienna or Paris.

- See Also: The Ultimate Guide to Driving in Iceland.

At the behest of her father, Ethel was advised to record her experiences in a journal. Ethel wrote of her time here in the book "A Girl's Ride in Iceland", (causing some controversy upon its release due to the publication's insistence that women be permitted to ride a horse without a side saddle... Scandalous!).

It is also worth noting that an appendix in the book, written by her father, is one of the first poetic tellings of visiting Iceland's impressive geysers.

Photo by Frederick W. W. Howell

Photo by Frederick W. W. Howell

The following is an extract written upon Ethel's arrival to Akureyri's harbour...

"The first thing that struck us on landing was the sad, dejected look of the men and women who surrounded us. There was neither life nor interest depicted on their faces, nothing but stolid indifference. This apathy is no doubt caused by the hard lives these people live, the intense cold they have to endure, and the absence of variety in their every-day existence. The Icelanders enjoy but little sun, and we know ourselves, in its absence, how sombre existence becomes. Their complexions too were very sallow and their deportment struck us as sadly sober."

A little harsh but, perhaps, on the money, given the conditions of Akureyri—and, in fact, much of Iceland—at that time. It is little surprise then that it was within the 20th Century, in particular, the years dogged by the horrors of the Second World War, where Akureyri would have its chance at redemption and growth.

As has been discussed in our previous articles, History of Iceland and The Icelandic Flag | A Tale of Identity, Iceland’s modernity only arose because of the presence of foreign troops, British, Canadian and American, on their shores. This 'preemptive' invasion, denying Iceland to the Axis Powers, led to an enormous push for modern infrastructure, as well as a cultural shift in the psyche of Icelanders themselves.

No longer were they isolated and untouchable; they had been forced onto the world stage for the very first time as an independent nation, responsible for its own affairs. Infrastructure in Iceland had become, for the first time, an economic necessity.

During WWII, Akureyri was used as an operating base for the Norwegian-British No. 330 Squadron of the Royal Air Force, who exercised Catalina flying boats and Northrop N3P-Bs from the area. These were used as a vital protection for Allied shipping between Europe and the United States, proving just how strategically important Iceland was to both sides of the conflict.

- See Also: How Expensive is Iceland?

By the end of the Second World War, Akureyri boasted a number of important industries that, by then, had cemented the settlement's importance to the country. Specifically, Akureyri locals had, under the cooperation and banner of the Eyjafjörður Co-operative Society, built up substantial employment sectors in fishing and agriculture, sectors that would only grow in strength as the years went by.

Akureyri Today

But what of Akureyri now? How has the city transformed over the last century to rightfully claim it's title as Iceland's northern capital? What does it offer that Iceland's actual capital, Reykjavík, does not? And what unique cultural traits have arisen from this city's rich and fascinating history?

Well, with a current population of approximately 19,000 people, Akureyri has managed to set itself aside as one of the Must-Visit destinations in Iceland. A quick glance at any Icelandic travel site will tell you just as much.

- See Also: Top 10 Things to Do in Akureyri.

This is, in large part, thanks to the country's booming tourism industry, a trend that has allowed Akureyri's powers-that-be to modernise and develop the city's infrastructure. Amongst the most popular tour options here include Whale Watching, hiking and visits to the beautiful and serene Lake Mývatn area.

Whale watching is looked upon particularly favourably here, given the sheer abundance of marine species in the neighbouring fjord—there are over twenty different species of cetacean that call Icelandic coastal waters home, with the major sightings being Minke Whales and Humpback Whales.

With stunning and eclectic surrounding scenery, a captivating local culture and a wealth of opportunities on offer, Akureyri successfully manages to offer its visitors something entirely unique in the pantheon of desirable Icelandic locations.

- See Also: History and Culture in Iceland.

Photo by Zheyun Wu

Photo by Zheyun Wu

Amenities, Attractions and Activities

One of Akureyri's major draws is the fact that it offers another built-up urban area aside from Reykjavík, something of a rarity in Iceland.

Here, visitors can enjoy all of the benefits associated with a modern-day city: a classy coffee culture, a colourful nightlife scene, beautiful street art, world class restaurants, classy hotels and local festivals with a variety of bands, performers and artists forever exhibiting their latest creative efforts. Not to forget their fantastic ski resort in winter and all year round access to one of Iceland's best swimming pools. It is, in short, a hip and happening spot.

- See Also: Music in Iceland.

There is also a wealth of fantastic architectural highlights to be found here. Of these, Akureyrarkirkja, the city's iconic Lutheran Church, is arguably the most impressive, with its tall, imposing pillars, mighty clock face and dramatic staircase. The church was designed by Guðjón Samúelsson, the then State Architect of Iceland, and completed in 1940.

Photo by Tobias Keller

Photo by Tobias Keller

Guðjón was also responsible for designing Hallgrímskirkja Church in Reykjavík, The University of Iceland and The National Theatre of Iceland, among many other buildings found across the country. As a testimony to the genius of Guðjón's style, upon the invasion of Iceland in 1940, the then-British Commander opted not to seize the University of Iceland building because he considered it "too beautiful".

Other noteworthy buildings worth checking out in Akureyri are Hof Cultural Centre (where you might catch some live music, get information on what's happening in town and grab a bite to eat) and the local theatre that was built in 1906 and to this day still puts on high class theatrical performances.

Many visitors to the north also manage to slip in a trip to the Akureyri Botanical Gardens. The garden is a result of a 1910 committee, the Park Society, which was established by the women of Akureyri as a means of beautifying their young city.

The park was opened in 1912, having been granted one hectare of the land by the council, but the society managed to extend this to three hectares by 1953. By 1957, the park was also being utilised for botany purposes.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Simone. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Simone. No edits made.

During this time, the park was used not only as a place of tranquillity for the locals but also for scientific research, proving that a variety of shrubs, flowers and trees can grow in such close proximity to the Arctic Circle. The Akureyri Botanical Gardens are one of the northernmost botanical gardens in the world.

- See Also: National Parks in Iceland.

That same year, 1957, a plant collection belonging to floral-enthusiast, Jón Rögnvaldsson, was bought, greatly expanding the park's variety of flora (a bust to Jón Rögnvaldsson can be seen in the park today, alongside other major contributors such as Margarethe Schiöth, former chairwoman of the park).

There are approximately 430 native Icelandic species of plant to check out at the Botanical Gardens, as well as over 7000 examples of alien species that have managed to grow here (—this, for reasons little known to me, puts one in mind of Jeff Goldblum's signature line, "Life finds a way..."). Without a doubt, the Botanical Gardens is one of the most colourful and rewarding locations to visit in Akureyri, providing a welcome break from the stresses of road travel and holiday itineraries.

- See Also: Wildlife and Animals in Iceland.

There are, naturally, other options for those looking to pace themselves whilst visiting Akureyri. For example, if there is one thing to be said of the northern capital, it is its abundance of museums and galleries, the perfect avocation for those hoping to gain a deeper insight into Iceland's, and Akureyri's, culture and history.

Photo by Lachlan Gowen

Photo by Lachlan Gowen

Among them are the Akureyri Art Museum (opened 1993, making it one of the city's oldest art establishments,) Akureyri Museum (focused on the city's absorbing story of settlement, growth and development), The Aviation Museum and The Motorcycle Museum of Iceland.

- See Also: Art Galleries in Reykjavik.

Those truly interested in finding out more about the city's history are also advised to take a stroll through Akureyri's "Old Town" where you will see the city's oldest building, Laxdalshús, constructed in 1778, as well as plenty of other examples of the region's architecture.

One of Akureyri's great attractions is its stark contrasts between architectural styles, balanced somewhere between modern and traditional Nordic. This makes taking a simple walk in the city a real pleasure.

Visitors could also make a stop at The Municipal Library, one of Iceland's largest bibliothecas, or even reach out to their inner-child with a short trip to The Toy Museum at Friðbjarnarhús, renowned for its enormous collection of model cars and dolls. Whatever your area of interest or passion, you're sure to find something in Akureyri that manages to meet, if not exceed your expectations.

Another point of interest; Akureyri outmatches many of its urban contemporaries thanks to the number of amenities present. Examples would be the city's domestic airport, Akureyrarflugvöllur, or the north's go-to education provider, the University of Akureyri ("Háskólinn á Akureyri "). Institutions such as this indicate just how far Akureyri has come from the days of here today, gone tomorrow traders.

- See Also: Studying in Iceland

Travelling to Akureyri

For those looking to visit Akureyri, there are a number of feasible travel options. First, and most obviously, it is advised that your rent your own vehicle whilst in Iceland.

This allows you to take the journey—roughly four and a half hour's northward of Reykjavik—at your own pace, as well as giving you the choice as to where and when you make stops enroute. It will also allow you to easily visit some of the natural attractions found nearby to Akureyri, such as Hlíðarfjall Mountain (famous for its thrilling ski resort) or Lake Mývatn.

Another option is to take a flight. There are direct flights available from both Reykjavík Domestic Airport and Keflavik International, both of which are offered by Air Iceland. Whilst Akureyri currently only holds a single-runway airport, there are plans in the future to expand the service.

Flights from Keflavík leave up to six times a week (though are only intended for those transferring from international flights), whilst flights leave several times a day from Reykjavík Domestic Airport. Both airports offer the service all year round, with flight times taking approximately forty-five minutes.

- See Also: Ultimate Guide to Flights to Iceland.

It is also possible to utilise this country's public transportation system. Bus transfers operated by Strætó and Sterna both make the journey from Reykjavík to Akureyri, though they differ in their routes and seasonal schedules.

Strætó operates all year to Akureyri and the surrounding area, taking Route 57 north. Sterna, on the other hand, only operates during the summer months, primarily using Route 60.

Did you enjoy our article, Akureyri | Iceland's "Capital of The North"? How did you find your time in Akureyri and what did you get up to? Are there any particular locations or activities you would recommend? Make sure to leave your thoughts and queries in the Facebook comments box below.

Altri articoli rilevanti

Location cinematografiche in Islanda: la lista completa

Quali film internazionali sono stati girati in Islanda? Perché i produttori di Hollywood scelgono di girare in Islanda? Scoprilo con il nostro elenco completo dei film internazionali girati nel pae...Leggi altroNatale in Islanda | La guida completa alle tradizioni natalizie, al cibo e a tanto altro ancora!

Scopri tutto sul Natale in Islanda. Quali sono le principali tradizioni natalizie islandesi? Perché l'Islanda ha 13 Yule Lads e non Babbo Natale? Come si festeggia il Natale in Islanda? Com'è il Nat...Leggi altro

Gli Yule Lads islandesi e Gryla | I troll di Natale in Islanda

Chi sono gli Yule Lads islandesi? Chi si festeggia in Islanda a Natale se non Babbo Natale? Che ruolo ha la gigantessa Gryla nel folklore natalizio islandese e chi è il gatto di Natale? Continua a l...Leggi altro

Scarica il più grande mercato di viaggi in Islanda sul telefono per gestire l'intero viaggio da un unico posto

Scansiona questo codice QR con la fotocamera del telefono e premi il link che compare per avere sempre in tasca il più grande mercato di viaggi in Islanda. Inserisci il numero di telefono o l'indirizzo e-mail per ricevere un SMS o un'e-mail con il link per il download.