Straddling the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and powered by a mantle hotspot, Iceland is a living geological showcase. From walking between continents at Thingvellir to soaking in geothermal hot spring pools, Iceland immerses visitors in active geology.

The country's use of geothermal power not only provides sustainable energy but also enhances the travel experience with naturally heated pools, spas, and warm rivers.

Why You Can Trust Our Content

Guide to Iceland is the most trusted travel platform in Iceland, helping millions of visitors each year. All our content is written and reviewed by local experts who are deeply familiar with Iceland. You can count on us for accurate, up-to-date, and trustworthy travel advice.

Exploring these sites often requires a rental car in Iceland, giving travellers the freedom to visit remote volcanic fields, glacier lagoons, and hot spring valleys at their own pace.

This guide covers the country’s most spectacular geological features and offers tips for exploring them safely and responsibly. Let’s dive in!

Iceland's Geological Origins & Timeline

Iceland is one of the youngest and most geologically active landmasses on Earth. It sits atop the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, where the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates are slowly drifting apart.

Iceland is one of the youngest and most geologically active landmasses on Earth. It sits atop the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, where the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates are slowly drifting apart.

This rift, combined with a powerful volcanic hotspot beneath the island, drives continuous geological formation. As the plates diverge, magma rises from the mantle, creating new crust and gradually building Iceland up from the seafloor.

The island first rose above the ocean about 16–18 million years ago, making it a baby in geological terms (for comparison, parts of Europe have rocks hundreds of millions of years old). The oldest exposed rocks in Iceland (in the far northwest, Westfjords, and eastern fjords) are around 16 million years old.

Thingvellir National Park, where the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates meet, is one of the few places on Earth to walk between two continents.

Meanwhile, the newest parts of Iceland are still forming today. The closer you get to the active rift zones in the center and southwest (like the Reykjanes Peninsula), the younger the land is. For example, the Reykjanes area in southwest Iceland is only about 7 million years old.

New volcanic islands can even appear: Surtsey, off the south coast, was born in a fiery eruption in 1963 and is one of the world’s youngest islands.

Volcanic Eruption, Eyjafjallajokull Glacier erupting in 2010, Iceland.

Key Geological Milestones

-

Surtsey Eruption (1963–1967): A new volcanic island off Iceland's south coast. UNESCO Surtsey

-

Laki Eruption (1783): Caused global climate anomalies and famine.

-

Eyjafjallajökull (2010): Grounded air traffic across Europe.

-

Fagradalsfjall Eruptions (2021–2025): Created hikeable lava fields and drew international visitors.

Iceland’s Main Rock Types Explained

Iceland’s geology is dominated by volcanic rocks formed through intense tectonic and volcanic activity. Located on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the island is geologically young and features a wide range of igneous rock types, primarily basalt, as well as rhyolite, tuff, tephra, palagonite, and hyaloclastite.

These rocks are the direct result of processes such as rapid lava cooling, explosive eruptions, and interactions between magma and water or ice. Their composition and formation history influence Iceland’s topography, soil characteristics, and natural landmarks.

The sections below provide an overview of Iceland’s major volcanic rock types, their formation, and their distribution across the country.

Basalt

Iceland’s primary rock type, basalt, is a dark, iron-rich volcanic rock formed by rapidly cooling lava. Found in iconic places like:

-

Eldhraun Lava Field

-

Svartifoss Waterfall (columnar basalt)

Basalt, Iceland’s most common volcanic rock, typically contains minerals like pyroxene and plagioclase, which range from 5 to 7 on the Mohs scale.

Inspired by the basalt column formations at Svartifoss Waterfall in Skaftafell, Hallgrímskirkja features a dramatic architectural design that echoes one of Iceland’s most iconic natural structures.

Designed by architect Guðjón Samúelsson in 1937, Hallgrímskirkja took over 40 years to complete and is now one of the most visited landmarks in Reykjavik.

Designed by architect Guðjón Samúelsson in 1937, Hallgrímskirkja took over 40 years to complete and is now one of the most visited landmarks in Reykjavik. It is a must-see attraction that reflects the natural artistry of Icelandic nature.

Designed by architect Guðjón Samúelsson in 1937, Hallgrímskirkja took over 40 years to complete and is now one of the most visited landmarks in Reykjavik. It is a must-see attraction that reflects the natural artistry of Icelandic nature.

Rhyolite

Rhyolite is a silica-rich volcanic rock formed during explosive eruptions, known for its vibrant colors ranging from red and pink to yellow and green.

Rhyolite is a silica-rich volcanic rock formed during explosive eruptions, known for its vibrant colors ranging from red and pink to yellow and green.

Rhyolite, richer in silica, can include quartz crystals that rate as high as 7.

Iceland creates striking mountain landscapes in places like Landmannalaugar and Kerlingarfjöll in the Highlands. These areas are famous for their multicolored hills and geothermal activity. Rhyolite is less common than basalt but adds unique visual diversity to Iceland’s interior regions.

Tuff, Tephra & Pyroclastics

Pyroclasts—from the Greek pyro (fire) and klastos (broken), are the fragmented materials ejected during explosive volcanic eruptions. These can include molten droplets, solidified magma, and shattered rock from the volcano itself.

Based on size, pyroclasts are classified as:

-

Ash (<2 mm)

-

Lapilli (2–64 mm)

-

Bombs and blocks (>64 mm)

Once settled, this material is known as "tephra". When tephra layers compact and harden, they form a type of volcanic rock called "tuff".

These fragments can be launched while still molten or partially molten, or they may be solidified magma or pieces of pre-existing rock. The Hverfjall volcano crater, pictured above, is a tephra cone also known as a tuff ring volcano, located in the Mývatn area. In Northern Iceland, ash layers from eruptions like Hekla and Askja are studied across Europe.

Palagonite & Hyaloclastite

Palagonite is a yellow-brown alteration product formed when water interacts with basaltic volcanic glass, typically at low temperatures.

Palagonite is a yellow-brown alteration product formed when water interacts with basaltic volcanic glass, typically at low temperatures.

It commonly forms when lava cools rapidly under water or in glaciers and is found in hyaloclastites, tuffs, and pillow lavas. Volcaniclastic rocks rich in palagonite are known as palagonite tuffs or breccias, once referred to as the "Palagonite Formation" in Iceland.

These formations are often seen in older geological units on the Snæfellsnes Peninsula or around Mýrdalsjökull and have been actively studied, including at Surtsey, where the transformation of basaltic tephra into palagonite tuff has been closely observed over time (Surtsey Research, 2025).

Icelandic Volcanoes and Lava Fields

Lava flows on an active volcano, aerial view of Mount Fagradalsfjall, Iceland.

Iceland’s very foundation is volcanic, with around 30 active volcanic systems and over 100 volcanoes shaping its rugged terrain. Eruptions occur roughly every 4–5 years, and in recent years, the Reykjanes Peninsula alone has experienced multiple eruptions, underscoring the island’s continuous geological activity.

This dynamic environment has produced a wide range of volcanic features, from lava plains and cone-shaped craters to colorful calderas.

Key highlights of Iceland’s volcanic landscape include:

Key highlights of Iceland’s volcanic landscape include:

-

Frequent eruptions: The Reykjanes Peninsula saw eruptions in 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024, and 2025, contributing to Iceland’s ever-changing surface.

-

Eruption styles vary:

-

Eyjafjallajökull (2010) emitted massive ash plumes, disrupting global air travel.

-

Fagradalsfjall (2021) produced slow-moving lava flows and created a hikeable lava field near Reykjavík.

-

-

Diverse lava formations:

-

Eldhraun Lava Field – a vast, moss-covered plain formed by the 1783 Laki eruption.

-

Dimmuborgir – surreal, castle-like lava formations near Lake Mývatn.

-

Kerið Crater and the Laki craters – accessible via guided super jeep tours in the South Iceland highlands.

-

Fagradalsfjall – a six-month eruption formed new craters and lava fields, which remain accessible to visitors today.

-

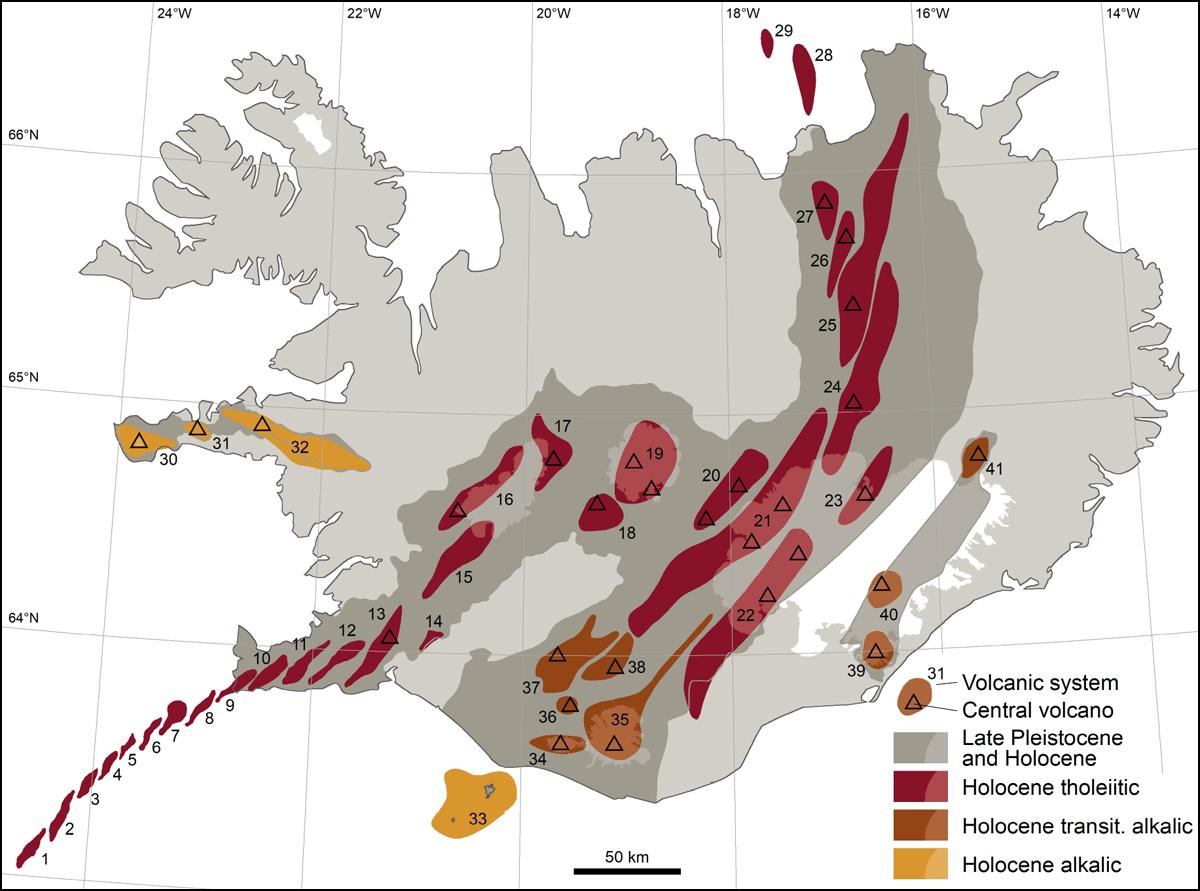

Volcanic systems in Iceland. Image credits to Ni.is.

As seen in the illustration above, the volcanic activity runs through the entire country. With over 30 active systems, eruptions are frequent. Iceland’s most famous volcanoes include:

-

Eyjafjallajökull (2010) – Disrupted global air travel.

-

Katla – Hidden under a glacier; overdue for eruption.

-

Fagradalsfjall (2021–2025) – A favorite for lava hikes. Book a small-group volcano hike with a geologist.

-

Askja – A remote caldera with otherworldly views.

For a once-in-a-lifetime experience, descend into the magma chamber of the dormant Thrihnukagigur volcano — the only place in the world where you can do this. Safety first: always stay on marked paths, check conditions, and go with a certified guide.

Tectonic Plates and Rift Zones You Can Walk On

Thingvellir National Park

Iceland lies atop the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a rift between the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates, and is literally pulling apart by about 2 cm each year. This tectonic activity gives rise to stunning rift valleys and fissures.

At Þingvellir National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, you can walk between two continents in the Almannagjá canyon. Another extraordinary experience is snorkeling in the Silfra fissure, where you float between tectonic plates in crystal-clear glacial water.

Midlina - the small symbolic footbridge between two continents in the Reykjanes Peninsula in Iceland

Further southwest, the "Bridge Between Continents" at Sandvík provides a symbolic photo op above a tectonic fissure. It is one of the few places on Earth where the Mid-Atlantic Ridge is visible above sea level, allowing you to literally walk between continents at places like Þingvellir National Park.

In the north, the Mývatn and Krafla volcanic zones demonstrate how rifting drives ongoing volcanic and geothermal activity. Frequent small earthquakes are common and are frequently felt in the capital area.

Check out the Iceland Geology Map Viewer, an interactive map hosted by the Icelandic Institute of Natural History (Náttúrufræðistofnun Íslands). This interactive ArcGIS-based map displays Iceland’s bedrock geology, volcanic zones, fissure swarms, and Holocene lava flows.

Thingvellir National Park

Located in a rift valley between two tectonic plates. A UNESCO World Heritage Site where you can self-drive or join a geology-focused walking tour.

Located in a rift valley between two tectonic plates. A UNESCO World Heritage Site where you can self-drive or join a geology-focused walking tour.

Silfra Fissure

Silfra is a glacial spring located in Thingvellir National Park, where the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates meet. Formed by tectonic rifting and filled with crystal-clear meltwater from the Langjökull glacier, Silfra offers underwater visibility of up to 100 meters, one of the clearest in the world.

It is the only place on Earth where you can swim directly between two continental plates. This experience is only possible with a certified Silfra guided tour, which provides all necessary gear and ensures safety in the cold, slow-moving water. Snorkeling or diving in Silfra is a bucket-list activity for geology and adventure lovers alike.

Krafla & Mývatn

Krafla and Mývatn, located in North Iceland, sit directly on the Mid-Atlantic Rift and are among the most geologically active areas in the country. The Krafla volcanic system has experienced multiple eruptions, including a notable series from 1975 to 1984, shaping the region’s dramatic lava fields and steaming vents.

Nearby, the Mývatn area features geothermal hot springs, pseudocraters, and colorful sulfuric landscapes, offering visitors a firsthand look at Iceland’s raw tectonic forces. This region is ideal for hiking, exploring volcanic formations, and learning about rift zone geology.

Before visiting these incredible sites, be sure to check the official source for safe travel in Iceland and the official Icelandic Met Office for the latest safety updates and tectonic activity alerts to ensure a safe and informed experience.

Icelandic Geothermal Wonders: Hot Springs, Energy, and Spa Culture

Volcanic heat fuels Iceland’s rich geothermal features. These include hot springs, fumaroles, mud pots, and geysers, many of which have become top tourist destinations.

Volcanic heat fuels Iceland’s rich geothermal features. These include hot springs, fumaroles, mud pots, and geysers, many of which have become top tourist destinations.

The Geysir geothermal area is home to the original Great Geysir (now mostly dormant) and Strokkur, which erupts every 5–10 minutes. Haukadalur Valley, where the geysers are located, is a must-visit on the Golden Circle.

People sitting in Reykjadalur, a hot river in Iceland in winter, in snowy mountains

Near Reykjavík, the Reykjadalur valley offers a hike to a thermal river where you can bathe in naturally hot water, a true reward after a scenic walk. In the north, Námaskarð (Hverir), near Lake Mývatn, offers a Mars-like experience of sulfuric steam and bubbling clay.

You can unwind at Mývatn Nature Baths or the world-famous Blue Lagoon as pictured below, located in a lava field near Keflavík Airport. Geothermal energy also powers homes and pools throughout Iceland, including Reykjavík’s many public thermal pools.

Icelandic Natural Wonders

Iceland’s raw landscape is shaped by fire, ice, and centuries of volcanic activity, making it a natural playground unlike anywhere else. From erupting geysers to geothermal spas, these striking sites offer a glimpse into the country’s untamed energy.

-

Strokkur Geyser erupts every 5 to 10 minutes.

-

Námaskarð (Hverir): Boiling mud pots and sulfur vents.

-

Reykjadalur Valley: A warm river for bathing.

-

Blue Lagoon & Mývatn Nature Baths: Geothermal spas fueled by volcanic heat.

Geothermal Energy in Iceland

Over 85% of Iceland’s homes are heated using geothermal energy, making it a global leader in renewable energy use. The Hellisheiði Power Plant, located near Reykjavík, has a visitor center that showcases Iceland’s innovative approach to geothermal power production.

To explore how geothermal systems work and where to see them in action, read an overview of geothermal areas in Iceland and this detailed feature on geothermal power in Iceland.

For those looking to experience it firsthand, don’t miss the top geothermal spas in Iceland, where natural heat meets relaxation and Icelandic scenery.

Caves and Lava Tunnels in Iceland

Iceland’s volcanic origin has created a vast network of lava tubes, ice caves, and underground caverns, offering unique opportunities to witness geology from the inside out.

Iceland’s volcanic origin has created a vast network of lava tubes, ice caves, and underground caverns, offering unique opportunities to witness geology from the inside out.

These caves form when lava flows cool and harden on the outside while molten lava continues to flow beneath the surface, eventually draining and leaving hollow tunnels behind.

Popular Caves to Explore:

Popular Caves to Explore:

-

Raufarhólshellir Lava Tunnel: Just 30 minutes from Reykjavík, this massive lava tunnel is nearly 1,400 meters long and features vivid mineral coloring and natural skylights.

-

Víðgelmir Lava Cave: Iceland’s largest lava cave by volume, located in the Hallmundarhraun lava field in West Iceland. Wooden walkways and lighting make it easy to explore.

-

Vatnshellir Cave: Located in the Snæfellsjökull National Park, this 8,000-year-old cave plunges 35 meters below the surface.

-

Ice Caves in Vatnajökull Glacier: Formed each winter by meltwater carving tunnels through glacial ice. Best explored from November to March with a certified guide.

These underground formations reveal layers of Iceland’s volcanic history frozen in time. From lava stalactites to glimmering ice walls, cave tours offer one of the most immersive geological experiences in the country. The best way to explore the Geology of Iceland is on caving tours with experienced guides.

Glaciers and Glacial Landscapes

Breathtaking view of Skaftafellsjokull glacier tongue and volcanic mountains in Skaftafell National Park, Skaftafellsjokull glacier, Iceland.

Glaciers cover approximately 10% of Iceland and have sculpted the country's valleys, lagoons, and fjords. The largest is Vatnajökull, which hides multiple volcanoes beneath its ice and feeds attractions like Jökulsárlón Glacier Lagoon.

Book a glacier hike on Sólheimajökull or Svínafellsjökull, or a winter blue ice cave tour. Other glaciers worth visiting include Langjökull (accessible by snowmobile and ice tunnel tours), Eyjafjallajökull, and Mýrdalsjökull. If you're planning a trek, be sure to check this guide on what to wear for glacier hikes.

Iceland’s fjords, particularly the Eastfjords and Westfjords, were carved by glacial movement during the last Ice Age. Even Reykjavík’s coastline bears glacial signatures.

Sadly, these glaciers are shrinking rapidly due to climate change. Since 1995, Iceland has lost around 7% of its glacier volume. Okjökull was officially declared a glacier-free area in 2014, marking the first named glacier in Iceland lost to climate change, according to the local Icelandic Met Office.

Major Glaciers and Glacier Attractions in Iceland

Iceland’s glaciers are not only breathtaking in scale and beauty, but they also offer some of the country’s most unforgettable travel experiences.

From shimmering ice caves and glacier hikes to iceberg-dotted lagoons and volcanic calderas hidden beneath the ice, these frozen giants showcase the powerful forces that continue to shape Iceland’s landscape.

Below are some of the most iconic and accessible glacier attractions across the island, each with its own unique features and adventures.

-

Vatnajökull – The Largest glacier in Europe. Offers ice cave tours.

-

Langjökull – Features a man-made tunnel for tours.

-

Mýrdalsjökull – Hides Katla volcano beneath.

-

Eyjafjallajökull – Famously erupted in 2010.

-

Jökulsárlón – A lagoon filled with icebergs.

-

Fjallsárlón – Less crowded and equally scenic.

-

Diamond Beach – A Nearby black beach with ice fragments.

Climate Change and Glacial Retreat

Iceland’s glaciers have been significantly impacted by climate change. Since 1995, the country has lost approximately 7% of its total glacier volume, driven by rising temperatures and altered precipitation patterns (UNESCO, 2023). This loss rate is among the highest in Europe and is transforming Iceland’s landscape and ecosystems.

Iceland’s glaciers have been significantly impacted by climate change. Since 1995, the country has lost approximately 7% of its total glacier volume, driven by rising temperatures and altered precipitation patterns (UNESCO, 2023). This loss rate is among the highest in Europe and is transforming Iceland’s landscape and ecosystems.

In 2014, Okjökull (also known as “Ok”), a glacier in west-central Iceland, was officially declared extinct. Once spanning 15 km²(5.8 mi²), it had diminished so much that it no longer met the criteria for glacial classification.

In 2019, a memorial plaque was placed at the site, titled “A Letter to the Future”, marking Iceland’s first named glacier lost to human-induced climate change (Rice University, 2019).

The impacts of glacier retreat in Iceland are broad and multifaceted:

The impacts of glacier retreat in Iceland are broad and multifaceted:

-

Hydrological Systems: The shrinking of glaciers is altering river flows, seasonal runoff, and aquatic ecosystems, with implications for hydroelectric power generation.

-

Tourism: Glacier hikes, ice cave tours, and snowmobiling activities are becoming less predictable and increasingly affected by unstable conditions.

-

Volcanic Activity: Glacial melting reduces pressure on magma chambers beneath the crust, potentially increasing the frequency of eruptions—a process known as glacial unloading (Sigmundsson et al., Nature Geoscience, 2010).

Ongoing monitoring by the Icelandic Meteorological Office (IMO) and glaciologists involves the use of satellite imagery, GPS field surveys, and aerial measurements across major ice caps, including Vatnajökull, Langjökull, and Hofsjökull.

Geology & Culture: Myths, Legends, and Lore

Iceland’s dramatic geology, including lava fields, volcanoes, geysers, and towering sea cliffs, is not only a scientific marvel but also a deep wellspring of Icelandic mythology and folklore.

Iceland’s dramatic geology, including lava fields, volcanoes, geysers, and towering sea cliffs, is not only a scientific marvel but also a deep wellspring of Icelandic mythology and folklore.

The natural forces shaping the island have long inspired tales of elves, trolls, spirits, and supernatural beings, weaving geology and culture together in uniquely Icelandic ways.

Huldufólk (Hidden People)

The Huldufólk, or "hidden people," are said to live in lava formations, hills, and rocks across the countryside. According to folklore, they are invisible to humans unless they choose to be seen.

The Huldufólk, or "hidden people," are said to live in lava formations, hills, and rocks across the countryside. According to folklore, they are invisible to humans unless they choose to be seen.

These elf-like beings are believed to protect the natural landscape, and many Icelanders still take their presence seriously. In fact, road projects have been rerouted or delayed to avoid disturbing rocks believed to be their homes.

Trolls and Stone Formations

Many sea stacks and rock formations, such as the Troll Waterfall near Reykjavik, and the iconic basalt stacks at Reynisfjara Beach, are said to be trolls that were turned to stone by the sun. These towering pillars serve as both geological features and mythic reminders of Iceland’s storytelling tradition,

Volcano Spirits & Norse Influence

The Norse sagas frequently associate volcanic eruptions with divine wrath or supernatural occurrences. For example, the catastrophic 1783 Laki eruption was widely interpreted by Icelanders at the time as a form of divine punishment.

To explore these stories further, visitors can learn more at the Saga Museum in Reykjavík, which brings Iceland’s mythological and historical heritage to life.

A Summary of the Geology of Iceland

From the depths of magma chambers to the crests of ancient glaciers, Iceland’s geology is a powerful reminder of Earth’s ever-changing nature. Few places allow you to hike an active volcano in the morning, bathe in a geothermal river by noon, and walk between tectonic plates before dinner.

This raw, rugged land doesn’t just tell the story of how our planet was shaped; it shows you, up close. To understand the power of the planet, there’s no better place to start than Iceland. Find your flights to Iceland and go see it for yourself.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Geology of Iceland

What type of geology does Iceland have?

Iceland’s geology is dominated by volcanic activity due to its position on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and above a hot spot. The island features basaltic lava fields, active volcanoes, geothermal areas, and glacially carved landscapes.

Why is Iceland geologically unique?

It’s one of the only places in the world where you can see tectonic plates diverging above sea level. Iceland also has new land formation (like Surtsey), numerous geothermal systems, and a combination of fire (volcanoes) and ice (glaciers) shaping its terrain.

How old is Iceland geologically?

Iceland is around 16–18 million years old, with the oldest rocks found in the Westfjords. It’s relatively young geologically, compared to continental landmasses that can be hundreds of millions of years old.

What are the best geological sites to visit in Iceland?

Top sites include Þingvellir National Park, Fagradalsfjall volcano, Reynisfjara black sand beach, Svartifoss waterfall, Stuðlagil Canyon, Námaskarð geothermal area, and Jökulsárlón Glacier Lagoon.

Is Iceland on a tectonic plate boundary?

Yes. Iceland sits on the boundary between the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates, which is why it's so geologically active. You can physically walk between the plates at Þingvellir.

How often do volcanoes erupt in Iceland?

On average, Iceland experiences a volcanic eruption every 4–5 years. Recent eruptions have occurred in the Reykjanes Peninsula (2021–2025) and previously at Eyjafjallajökull in 2010.

Is it safe to visit Iceland’s volcanoes and geothermal areas?

Yes, if you follow official guidelines. Always check SafeTravel and Vedur for updates, avoid restricted areas, and go with certified guides when visiting volcanoes or glaciers.

Can you see tectonic plates in Iceland?

Yes. The best place is at Þingvellir National Park, where you can walk between the plates. You can even snorkel in the Silfra fissure, floating directly between North America and Europe.

Are there glaciers on top of volcanoes in Iceland?

Yes. Several glaciers like Mýrdalsjökull and Vatnajökull cover active volcanoes, leading to the phenomenon of jökulhlaups (glacial floods) when eruptions occur beneath the ice.

How is climate change affecting Iceland’s geology?

Glaciers are rapidly retreating. Iceland has lost about 7% of its glacier volume since 1995. This affects river systems, sea levels, and may also impact volcanic activity due to changes in crustal pressure.