Iceland preserves something extraordinary: a living connection to the Viking Age, where Old Norse culture remains directly accessible through language, literature, and immersive Viking history and saga experiences.

Here, you can read 800-year-old texts in a language still spoken today, explore the Viking parliament founded in 930 AD on Thingvellir tours, or follow the footsteps of Norse settlers.

Why You Can Trust Our Content

Guide to Iceland is the most trusted travel platform in Iceland, helping millions of visitors each year. All our content is written and reviewed by local experts who are deeply familiar with Iceland. You can count on us for accurate, up-to-date, and trustworthy travel advice.

This guide covers Viking history in Iceland, from the first settlers and their daily lives to Norse gods, Icelandic sagas, and magical traditions. Discover key historical museums, saga sites, festivals, and immersive experiences that bring the Viking Age vividly to life.

Read on to find out why Iceland remains the ultimate destination to walk in the footsteps of Vikings and early settlers to connect with their enduring legacy.

What You Need to Know About Vikings in Iceland

-

Vikings began settling Iceland around 870 AD, mainly Norwegian farmers and traders, with many women of Celtic ancestry contributing to the population.

-

Icelandic Vikings focused on farming and community life, creating the Althingi parliament in 930 AD and local assemblies to resolve disputes peacefully.

-

Farming, fishing, and craftsmanship sustained communities. Women had notable legal and economic rights, managing property and trade.

-

Iceland preserved Norse culture and language. Modern Icelandic is close to Old Norse, allowing access to medieval sagas and literature.

-

Thor was the most prominent god among Icelandic Vikings, while Odin, Freyja, and Freyr remained part of the broader Norse belief system. Volvas used prophecy and magic to guide communities in daily matters.

-

Iceland converted peacefully to Christianity in 999/1000 AD, keeping cultural continuity while adopting the new faith.

-

Iceland offers a living Viking connection through preserved sites, museums, festivals, and landscapes described in the sagas.

How Icelandic Vikings Differed From Scandinavian Vikings

Before sailing to Iceland, many of the first Viking settlers had lived in Norse colonies across the British Isles, where they gained experience in establishing new communities and managing farmland.

Their population was more diverse than often assumed, as genetic studies indicate that roughly 60% of founding Icelandic women had Celtic ancestry, primarily from Ireland and Scotland. These women arrived as wives, slaves, or free settlers from mixed Norse-Celtic communities.

Icelandic Vikings prioritized building a stable society rather than raiding like their mainland counterparts. The island’s isolation and abundant natural resources made farming and fishing the primary sources of sustenance.

Communities developed around farms and local assemblies, creating social structures and governance practices that differed significantly from mainland Scandinavia.

These unique conditions shaped a society that diverged in several key ways:

-

Political Structure: Iceland rejected kingship, forming a commonwealth governed by chieftains and assemblies.

-

Military Activity: Icelanders prioritized farming and internal disputes rather than raids and conquests.

-

Cultural Preservation: Norse mythology, poetry, and oral traditions were preserved and later recorded in sagas.

-

Language and Literature: The Icelandic language remained close to Old Norse, allowing sagas and eddas to be read today.

-

Conversion to Christianity: Adopted through a parliamentary vote in 1000 AD, with temporary allowances for pagan practices.

This combination of settlement, governance, and cultural preservation makes Icelandic Vikings uniquely valuable for understanding Viking Age life.

While mainland Scandinavia provides archaeological evidence of Viking activity, Iceland preserves the literature, language, and cultural memory that bring the era to life.

Famous Viking Settlers in Iceland

Several prominent figures shaped early Iceland, and the list below represents only a fraction of the remarkable individuals who shaped Icelandic society during the Viking Age. Many other explorers, warriors, poets, and leaders also left lasting impacts, and their stories are preserved in sagas, historical records, and the island’s cultural memory.

Several prominent figures shaped early Iceland, and the list below represents only a fraction of the remarkable individuals who shaped Icelandic society during the Viking Age. Many other explorers, warriors, poets, and leaders also left lasting impacts, and their stories are preserved in sagas, historical records, and the island’s cultural memory.

Ingólfur Arnarson

Ingólfur Arnarson is traditionally credited as Iceland's first permanent settler around 874 AD. According to the sagas, he threw his high seat pillars overboard as he approached the island and claimed land wherever they washed ashore. The pillars landed at Reykjavik, or "Smoky Bay," named for the geothermal steam rising from hot springs. His farm became the foundation for Iceland's future capital.

Auður djúpúðga

Auður djúpúðga, or Audur the Deep-Minded, claimed extensive territory in western Iceland during the 890s after her husband and son died in battle in Scotland and Ireland.

Auður djúpúðga, or Audur the Deep-Minded, claimed extensive territory in western Iceland during the 890s after her husband and son died in battle in Scotland and Ireland.

A Christian in a pagan age, she freed her enslaved workers and granted them land. Her descendants went on to become one of Iceland's most powerful families in Iceland. Her life and legacy are chronicled in the Laxdaela saga.

Egill Skallagrímsson

Egill Skallagrímsson was Iceland's most famous Viking Age poet and warrior. His life combined violence, litigation, poetry, and politics. Egils saga recounts his legendary conflicts with Norwegian kings, narrow escapes from execution, and the powerful poetry he composed.

He was born around the year 910 in Borg a Myrum in West Iceland, a farm that remained in his family for generations. Today, visitors can explore the events of Egils saga at the Settlement Center in Borgarnes.

Erik the Red

Exiled from Norway for manslaughter and later from Iceland for the same offense, Erik the Red explored and settled Greenland around 985 AD, establishing Norse colonies that lasted nearly 500 years.

His son, Leif Erikson, would later reach North America. Erik’s farm at Eiriksstadir in the Haukadalur Valley has been reconstructed and is open to visitors.

Snorri Sturluson

Snorri Sturluson lived from 1179 to 1241 during Iceland’s final century of independence. A poet, historian, and politician, he wrote the Prose Edda, which preserved more Norse mythology than any other source, and Heimskringla, the definitive history of Norwegian kings.

His literary achievements made him medieval Iceland’s most important intellectual figure. He lived at Reykholt in West Iceland, where his medieval hot spring bath still exists.

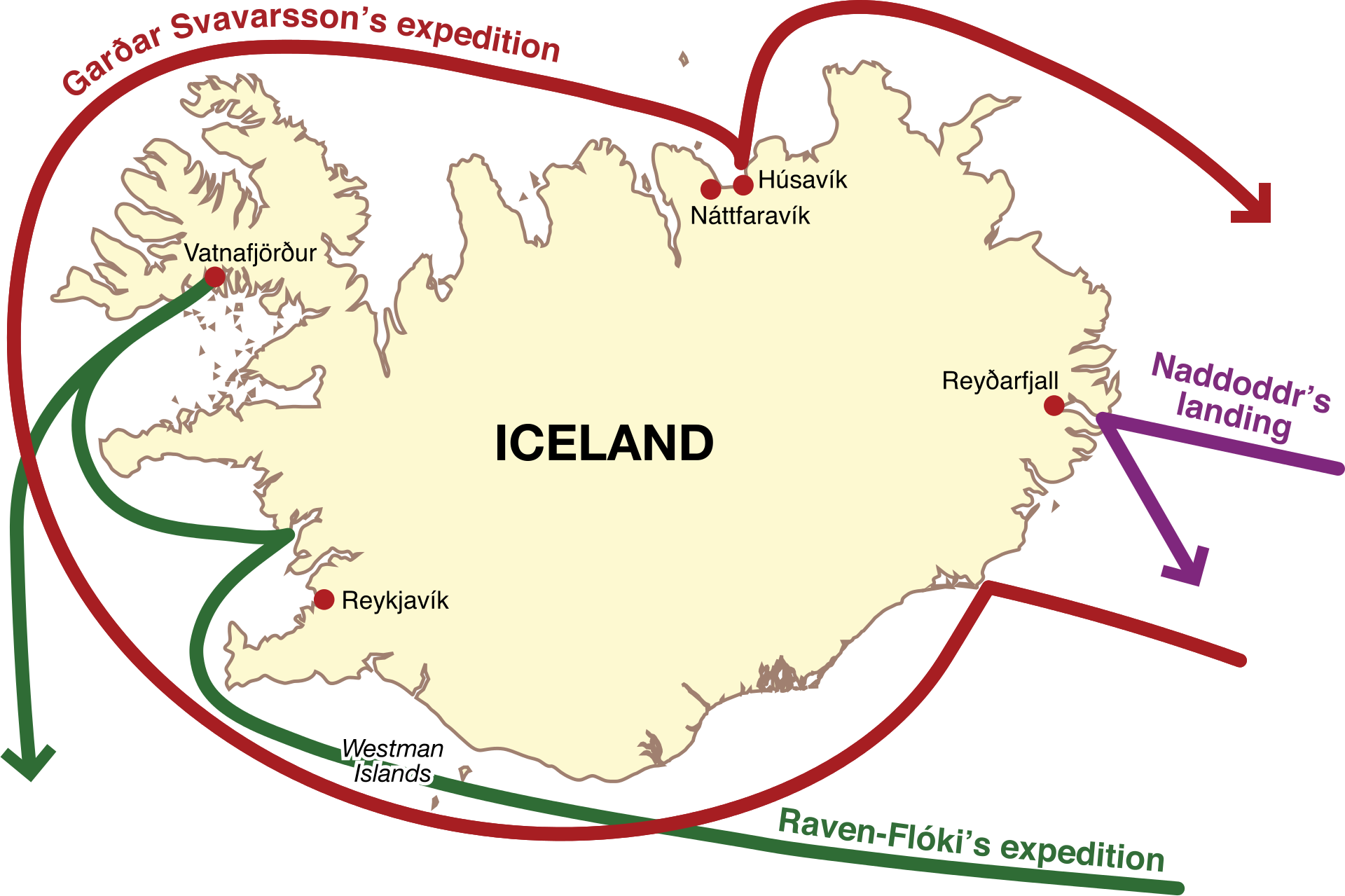

Other notable figures include Hrafna-Flóki Vilgerðarson, who gave Iceland its name, Gunnar Hámundarson, the warrior celebrated in Njáls saga, and Þorfinn Karlsefni, the explorer who led an expedition to Vinland. Their lives shaped the early population of Iceland and laid the groundwork for the communities, customs, and beliefs that defined life in Viking Age Iceland.

Life in Viking Age Iceland

Icelandic Vikings adapted quickly to the island’s harsh and isolated environment, creating communities that balanced survival, social organization, and cultural continuity. Daily life revolved around farming, fishing, craftsmanship, and trade, while social structures emphasized cooperation and long-term stability.

Icelandic Vikings adapted quickly to the island’s harsh and isolated environment, creating communities that balanced survival, social organization, and cultural continuity. Daily life revolved around farming, fishing, craftsmanship, and trade, while social structures emphasized cooperation and long-term stability.

These practices laid the foundations of Icelandic society and influenced the traditions, beliefs, and routines that defined life during the Viking Age.

The Thing System: Governance Among Icelandic Vikings

Iceland developed a political system remarkable for its time. Free landowners established the Althingi, the world’s oldest surviving parliament, at Thingvellir National Park in 930 AD. This Icelandic Commonwealth functioned as a limited democracy, where free men who owned property could participate in decision-making.

Iceland developed a political system remarkable for its time. Free landowners established the Althingi, the world’s oldest surviving parliament, at Thingvellir National Park in 930 AD. This Icelandic Commonwealth functioned as a limited democracy, where free men who owned property could participate in decision-making.

Local assemblies, called things or “Þing” in Icelandic, handled regional disputes, while the Althingi met each summer for two weeks, serving as legislature, supreme court, and social gathering. Chieftains, known as godar, held authority based on their ability to attract followers rather than fixed territorial control. Disputes were resolved through arbitration, compensation, or occasionally duels, emphasizing law, reputation, and negotiation over military power.

Thingvellir, a dramatic rift valley formed by the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates, provided natural acoustics for public speeches. Today, it is a UNESCO World Heritage site and a key stop on Iceland’s Golden Circle sightseeing route.

Economy and Daily Life in Viking Age Iceland

Farming formed the backbone of daily life in early Icelandic society, and its legacy can be explored today at Viking‑era sites like The Commonwealth Farm in South Iceland, Hofsstadir in the Capital Region, and Eiriksstadir in West Iceland.

Farming formed the backbone of daily life in early Icelandic society, and its legacy can be explored today at Viking‑era sites like The Commonwealth Farm in South Iceland, Hofsstadir in the Capital Region, and Eiriksstadir in West Iceland.

Icelandic sheep were especially valuable, providing meat, milk, and wool, while cattle and goats rounded out food production. Icelandic horses and oxen did the heavy work, and barley was grown when the weather allowed, though climate changes eventually restricted grain production.

Iceland’s surrounding waters became just as important as its fields. Fishing grew into a vital part of the diet, with coastal settlements harvesting cod, haddock, and other marine species. Whale and seal hunting added to these protein sources, and the practice of salting and drying fish ensured both long-term storage and reliable goods for trade.

Through this maritime economy, Iceland became increasingly connected to broader Scandinavian trade networks. Archaeological discoveries reveal the extent of these connections: silk from Byzantium, glass beads from the Mediterranean, and silver from the Middle East all reached Icelandic shores. In return, Iceland exported wool cloth, sulfur, falcons, and a variety of marine products.

To support both household life and commercial activity, settlers developed impressive technical skills. Craftsmanship flourished, with high standards in shipbuilding, metalwork, woodcarving, and textile production.

Within this society, women held significant legal and economic rights compared to many contemporary European cultures. They could own property, inherit land, manage farms, and even initiate divorce. Though not equal by modern standards, these rights align with the cultural roots of the gender equality Iceland is known for today.

Women’s central role in textile production, especially the creation of wool cloth known as “vaðmál” used in trade, further increased their economic influence. Some women also practiced seidr, a form of Norse magic tied to prophecy and ritual, which granted them notable spiritual authority.

Viking Foods in Iceland: What Did Vikings Eat?

Icelandic Vikings relied on foods sourced from the island and the surrounding seas to sustain themselves through the long, harsh winters. Much like food in Iceland today, preservation methods such as smoking, drying, and fermenting were essential, allowing staples to last when fresh provisions were scarce.

Icelandic Vikings relied on foods sourced from the island and the surrounding seas to sustain themselves through the long, harsh winters. Much like food in Iceland today, preservation methods such as smoking, drying, and fermenting were essential, allowing staples to last when fresh provisions were scarce.

Their everyday diet included skyr, hardfiskur (dried fish), hangikjot (smoked lamb), flatkaka (flatbread), and blodmor (blood pudding), which foreigners often consider one of the less-appealing Icelandic foods. When weather permitted, barley was grown for simple breads and porridges, while wild berries, herbs, Icelandic moss, and seaweed added flavor and nutrition.

Food also played a central role in social life. Feasts celebrated religious ceremonies, seasonal cycles, and important community events, often accompanied by storytelling, poetry, and communal drinking. Trade occasionally brought imported goods such as honey, butter, and spices, adding new flavors and variety to their tables.

Vikings and Norse Gods in Iceland

The Icelandic settlers brought Norse beliefs from Scandinavia, but life on the island shaped how these traditions were practiced. Farming, fishing, and community life demanded careful planning and cooperation. To ensure success and protection, Icelanders turned to the Norse gods, seeking guidance, favor, and security through rituals, offerings, and magical practices.

The Icelandic settlers brought Norse beliefs from Scandinavia, but life on the island shaped how these traditions were practiced. Farming, fishing, and community life demanded careful planning and cooperation. To ensure success and protection, Icelanders turned to the Norse gods, seeking guidance, favor, and security through rituals, offerings, and magical practices.

Before Christianity, Icelanders honored a pantheon of gods connected to natural forces, human activities, and abstract concepts, making offerings to secure good harvests, successful voyages, victory in disputes, or healthy children. Worship took place at natural sites, in dedicated temples called hof, or in private homes. Major ceremonies, called blot, are believed to have involved animal sacrifice, feasting, and communal drinking, which reinforced both social bonds and spiritual devotion.

Volvas, female seers, practiced divination and prophecy. Sagas describe them traveling between farms during winter, performing ceremonies to predict the coming year's fortune. Their spiritual authority operated independently of political power structures.

Within this rich spiritual framework, certain deities held particular importance for Icelandic settlers:

Thor (Þór)

Thor, the thunder god, was the most popular deity among Icelandic Vikings. He protected both gods and humans, symbolizing strength, reliability, and defense against chaos. He wielded the hammer Mjollnir and wore the belt Megingjord, which doubled his already formidable power. Many settlers named farms and children after Thor.

His name survives in Thursday (Þórsdagur) across Germanic languages, and Roman writers equated him with Jupiter when naming the days of the week.

Odin (Óðinn)

Odin, the Allfather, ruled the Aesir gods. Associated with war, death, wisdom, and poetry, he sought knowledge relentlessly, sacrificing his eye for wisdom and hanging on Yggdrasil, the world tree, to learn the runes. He presided over Valhalla, where warriors who died in battle feasted until Ragnarok. From his high seat Hlidskjalf, he observed all nine worlds.

Odin’s eight-legged horse Sleipnir is linked to Icelandic folklore, including the shape of Asbyrgi Canyon. His name gives Wednesday (Óðinsdagur).

Freyja

Freyja, goddess of love, fertility, beauty, and war, was widely worshipped in Iceland. She practiced seidr, a form of magic, and taught it to Odin. Half of those who died in battle went to her hall Folkvangr, and the other half to Valhalla. She wore the necklace Brisingamen and traveled in a chariot pulled by cats. Her name means "lady" and survives in Friday (Frjádagur).

Freyr

Freyr, Freyja’s brother, governed fertility, prosperity, fair weather, and peace. Farmers invoked him for good harvests. He owned the ship Skidbladnir, which could carry all the gods yet fold small enough to fit in a pocket, and the boar Gullinbursti, whose golden bristles lit the way.

Loki

Loki, of giant ancestry but living among the gods, was a cunning trickster who caused both harm and help. His actions eventually set Ragnarok in motion, the end of the world. His children included Fenrir the wolf, Hel, goddess of death, and Jormungandr, the World Serpent.

Baldr

Baldr, Odin’s beloved son, embodied light, innocence, and purity. His death, caused by Loki’s trickery, brought great mourning among the gods and foreshadowed their eventual doom.

Frigg

Frigg, Odin’s wife, governed marriage, childbirth, domestic life, and foresight. Women called on her during labor and household matters. Some traditions link her closely with Freyja, and they may have originally been the same god, though medieval sources treat them as separate deities.

Frigg, Odin’s wife, governed marriage, childbirth, domestic life, and foresight. Women called on her during labor and household matters. Some traditions link her closely with Freyja, and they may have originally been the same god, though medieval sources treat them as separate deities.

The gods were not isolated figures. They existed within a complex universe that shaped how Icelanders understood the natural world, fate, and human action. Belief in these deities extended into cosmology, explaining the structure of the universe, and into practical magic.

Cosmology and Magic in Viking Iceland

Norse mythology described a universe of nine worlds, all connected by Yggdrasil, the immense ash tree. These included Asgard (Ásgarðr), home of the Aesir gods; Midgard (Miðgarðr), the human world; Jotunheim (Jötunheimr), land of giants; and Hel, the realm of the dead. This interconnected cosmos reflected a worldview in which gods, humans, giants, elves, and dwarves all shared a larger destiny that culminated in Ragnarok, the end of the gods and the world’s renewal.

Norse mythology described a universe of nine worlds, all connected by Yggdrasil, the immense ash tree. These included Asgard (Ásgarðr), home of the Aesir gods; Midgard (Miðgarðr), the human world; Jotunheim (Jötunheimr), land of giants; and Hel, the realm of the dead. This interconnected cosmos reflected a worldview in which gods, humans, giants, elves, and dwarves all shared a larger destiny that culminated in Ragnarok, the end of the gods and the world’s renewal.

Belief in the gods extended into practical magic, which guided daily activities. Runes served not only as an alphabet but also as symbols imbued with magical power, carved on weapons, memorial stones, and everyday objects to protect, bless, or influence outcomes.

In Iceland, magical practices evolved distinctive forms called Galdrastafir, or magical staves, which combined runes into intricate designs to ensure protection, love, or other benefits. These practices persisted for generations. By the late 10th century, however, Christianity arrived, and Iceland faced a choice: maintain the old ways or adopt the new faith.

Christianization and Preservation of Norse Culture in Iceland

Iceland's conversion to Christianity happened through political decision rather than conquest. By the late 10th century, pressure from Norway’s King Óláfr Tryggvason, combined with Icelanders’ exposure to Christian lands, created tension between Christian and pagan factions.

Iceland's conversion to Christianity happened through political decision rather than conquest. By the late 10th century, pressure from Norway’s King Óláfr Tryggvason, combined with Icelanders’ exposure to Christian lands, created tension between Christian and pagan factions.

As civil war loomed, the lawspeaker Þorgeir Ljósvetningagoði spent a day and night in contemplation before making a pragmatic decision: Christianity would become the law of the land. This choice preserved unity while temporarily allowing some pagan practices to continue in private.

According to legend, Þorgeir cast his pagan idols into Godafoss, the "Waterfall of the Gods," giving the site its enduring name. Whether fact or story, the waterfall remains a powerful symbol of Iceland’s religious transformation, offering visitors a tangible connection to this pivotal moment in history.

Even as Christianity spread, Icelanders preserved their cultural memory through the written word. Between the 12th and 14th centuries, they recorded family sagas, kings’ sagas, and legendary tales in the vernacular Icelandic language. These sagas captured the deeds of both heroes and ordinary people, preserving genealogies, legal traditions, and historical events.

Two works stand out: the Poetic Edda, a collection of ancient oral poems about gods and heroes, and the Prose Edda, compiled by Snorri Sturluson to explain mythology and guide poets.

Iceland’s relative isolation and strong oral traditions allowed these texts to survive where much of pagan material elsewhere in Scandinavia was lost. Even today, modern Icelandic remains remarkably close to Old Norse, enabling readers to experience the Viking Age almost firsthand.

For anyone visiting Iceland, the sagas and the landscapes they describe make the culture, beliefs, and people of the Viking Age feel immediate and alive.

11 Best Places to Experience Viking History in Iceland

From saga landscapes and preserved turf houses to the best museums in Iceland, these 11 sites let you experience Viking history up close and authentically.

From saga landscapes and preserved turf houses to the best museums in Iceland, these 11 sites let you experience Viking history up close and authentically.

11. The Saga Museum

The Saga Museum brings Icelandic history to life using life-size figures and immersive settings. The exhibits recreate moments from Viking Age settlement, conversion, and saga events, emphasizing storytelling over original artifacts. It’s a fun introduction to Icelandic Vikings.

The Saga Museum brings Icelandic history to life using life-size figures and immersive settings. The exhibits recreate moments from Viking Age settlement, conversion, and saga events, emphasizing storytelling over original artifacts. It’s a fun introduction to Icelandic Vikings.

-

Admission: Tickets are required

-

Location and Directions: Grandagardur 2, 101 Reykjavik, Iceland

-

Distance From Reykjavik City Center: 0.6 miles (1 kilometer)

10. Viking World Museum

The Viking World Museum explores Viking seafaring technology and Scandinavian Viking Age culture, featuring Islendingur, a full-scale Viking ship replica that sailed to North America in 2000. Its location in the town of Keflavik by Keflavik International Airport makes it convenient for a brief stop.

The Viking World Museum explores Viking seafaring technology and Scandinavian Viking Age culture, featuring Islendingur, a full-scale Viking ship replica that sailed to North America in 2000. Its location in the town of Keflavik by Keflavik International Airport makes it convenient for a brief stop.

-

Admission: Tickets are required, with an option to reserve online

-

Location and Directions: Reykjanesbaer, Vikingabraut 1, 260 Njardvik, Iceland

-

Distance From Reykjavik City Center: 28 miles (45 kilometers)

9. Glaumbaer Farm and Museum

Glaumbaer Farm and Museum in Skagafjordur Fjord preserves a turf farm complex showing centuries of Icelandic rural life. While the standing buildings date mainly from the 18th century, the layout and construction reflect medieval patterns, offering context for saga-age living in North Iceland.

Glaumbaer Farm and Museum in Skagafjordur Fjord preserves a turf farm complex showing centuries of Icelandic rural life. While the standing buildings date mainly from the 18th century, the layout and construction reflect medieval patterns, offering context for saga-age living in North Iceland.

-

Admission: Tickets are required

-

Location and Directions: 561 Glaumbaer, Iceland

-

Distance From Reykjavik City Center: 168 miles (270 kilometers)

8. Eiriksstadir Viking Longhouse

Eiriksstadir in West Iceland is the reconstructed turf longhouse farm of Erik the Red and his son Leif Erikson. Costumed guides demonstrate Viking Age crafts and recount Greenland and North American voyages. The site operates seasonally, typically June through August.

-

Admission: Tickets are required for the full guided tour inside the longhouse

-

Location and Directions: Haukadalsvegur, 371 Budardalur, Iceland

-

Distance From Reykjavik City Center: 75 miles (120 kilometers); also accessible on Ring Road tours

7. The Settlement Exhibition

The Settlement Exhibition in Reykjavik is built around a 10th-century longhouse discovered during construction. Here, visitors can view original artifacts and interactive displays about daily life, construction, and settlement. Located beneath Reykjavik’s streets, it provides a tangible, ground-level connection to Viking Age Iceland.

The Settlement Exhibition in Reykjavik is built around a 10th-century longhouse discovered during construction. Here, visitors can view original artifacts and interactive displays about daily life, construction, and settlement. Located beneath Reykjavik’s streets, it provides a tangible, ground-level connection to Viking Age Iceland.

-

Admission: Tickets are required, but admission is included with the 24-hour, 48-hour, or 72-hour Reykjavik Card

-

Location and Directions: Adalstraeti 16, 101 Reykjavik, Iceland

-

Distance From Reykjavik City Center: Central, walkable

6. Stong and Thjodveldisbaerinn

Stong is a Viking Age farm buried by the 1104 Hekla Volcano eruption, and Thjodveldisbaerinn is its full-scale reconstruction. Visitors can explore the longhouse, central hearth, sleeping benches, and dairy room, gaining insight into the life of wealthy Viking Age families.

Stong is a Viking Age farm buried by the 1104 Hekla Volcano eruption, and Thjodveldisbaerinn is its full-scale reconstruction. Visitors can explore the longhouse, central hearth, sleeping benches, and dairy room, gaining insight into the life of wealthy Viking Age families.

-

Admission: Tickets are required

-

Location and Directions: Thjodveldisbaerinn, 804 Selfoss, Iceland

-

Distance From Reykjavik City Center: 56 miles (90 kilometers); also accessible via guided South Coast tours

5. The Saga Centre

The Saga Centre in Hvolsvollur focuses on Njáls saga, one of Iceland’s most famous sagas. Interactive exhibits explain the story, while guided tours connect narrative events to nearby landscapes. It’s ideal for travelers interested in literary and historical context.

The Saga Centre in Hvolsvollur focuses on Njáls saga, one of Iceland’s most famous sagas. Interactive exhibits explain the story, while guided tours connect narrative events to nearby landscapes. It’s ideal for travelers interested in literary and historical context.

-

Admission: Tickets are required once the site reopens following renovations

-

Location and Directions: Grundargata 35, 350 Grundarfjordur, Iceland

-

Distance From Reykjavik City Center: 62 miles (100 kilometers)

4. Snorrastofa

-

Admission: Tickets are required

-

Location and Directions: Halsasveitavegur, 320 Reykholt, Iceland

-

Distance From Reykjavik City Center: 68 miles (109 kilometers); also accessible on Snaefellsnes tours

3. The National Museum of Iceland

The National Museum of Iceland houses the country’s most comprehensive Viking Age collection, including tools, weapons, jewelry, and religious objects. The medieval exhibition highlights both pagan and Christian material culture, with Thor’s hammers alongside crosses, illustrating the religious transition.

The National Museum of Iceland houses the country’s most comprehensive Viking Age collection, including tools, weapons, jewelry, and religious objects. The medieval exhibition highlights both pagan and Christian material culture, with Thor’s hammers alongside crosses, illustrating the religious transition.

-

Admission: Tickets are required, but admission is included with the 24-hour, 48-hour, or 72-hour Reykjavik Card

-

Location and Directions: Sudurgata 41, 102 Reykjavik, Iceland

-

Distance From Reykjavik City Center: Central, walkable

2. Godafoss Waterfall

Godafoss, the “Waterfall of the Gods,” marks an important site in Iceland’s religious conversion, and it’s one of the top Ring Road attractions. When Iceland converted to Christianity, the lawspeaker Þorgeir Ljósvetningagoði is said to have symbolically thrown his pagan idols into this waterfall. Visitors can enjoy stunning views and contemplate the history. Minimal walking from the parking area makes it accessible year-round.

-

Admission: Free

-

Location and Directions: Godafoss, 640 Myvatn, Iceland

-

Distance From Reykjavik City Center: 261 miles (420 kilometers); also accessible via guided tours from Akureyri

1. Thingvellir National Park

Thingvellir National Park is a UNESCO World Heritage site and the location of Iceland’s Alþingi from 930 until 1798. Visitors can walk to Logberg (Law Rock), see Drekkingarhylur (drowning pool), and explore the dramatic rift valley where the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates diverge. The park combines natural beauty with a deep connection to Icelandic law and Viking heritage.

Thingvellir National Park is a UNESCO World Heritage site and the location of Iceland’s Alþingi from 930 until 1798. Visitors can walk to Logberg (Law Rock), see Drekkingarhylur (drowning pool), and explore the dramatic rift valley where the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates diverge. The park combines natural beauty with a deep connection to Icelandic law and Viking heritage.

-

Admission: Free

-

Location and Directions: 806 Selfoss, Iceland

-

Distance From Reykjavik City Center: 31 miles (50 kilometers); also accessible on self-drives and Golden Circle tours

Viking Heritage Festivals and Events in Iceland

After exploring Iceland’s most iconic Viking sites, you can dive even deeper into the past by attending Viking heritage festivals and events in Iceland. These lively gatherings bring history to life with reenactments, crafts, storytelling, and feasts, offering visitors a hands-on way to experience the culture, customs, and daily life of the Viking Age.

Hafnarfjordur Viking Festival

Visitors can try archery, watch blacksmithing, hear Viking storytelling, and sample foods inspired by the Norse era. This festival is perfect for families, history enthusiasts, and anyone wanting to step into the Viking Age.

Medieval Days at Gasir

Step back in time at Gasir in North Iceland’s Eyjafjordur during early July, the site of one of Iceland’s most important Viking Age trading posts. Reenactors recreate a bustling medieval marketplace, demonstrating period crafts and performing historical scenarios. Visitors can explore the daily life of traders, craftsmen, and Vikings, gaining insight into Iceland’s economic and cultural history while enjoying an interactive and engaging festival experience.

Step back in time at Gasir in North Iceland’s Eyjafjordur during early July, the site of one of Iceland’s most important Viking Age trading posts. Reenactors recreate a bustling medieval marketplace, demonstrating period crafts and performing historical scenarios. Visitors can explore the daily life of traders, craftsmen, and Vikings, gaining insight into Iceland’s economic and cultural history while enjoying an interactive and engaging festival experience.

In addition to these festivals, Icelandic museums also host Viking-themed events throughout the year. Reenactors demonstrate crafts, combat techniques, and everyday life from the Viking Age. These events complement exhibitions and provide a dynamic way to experience Iceland’s Viking heritage, making both museums and festivals essential stops for anyone wanting to step into the Norse past.

Planning Your Viking Heritage Trip in Iceland

Iceland’s Viking heritage comes alive not only through its festivals but also through immersive Viking history and saga tours. From guided walking tours through Reykjavik’s historic sites to horseback rides across scenic landscapes, these experiences bring the Viking Age and Icelandic sagas vividly to life for travelers of all interests.

Iceland’s Viking heritage comes alive not only through its festivals but also through immersive Viking history and saga tours. From guided walking tours through Reykjavik’s historic sites to horseback rides across scenic landscapes, these experiences bring the Viking Age and Icelandic sagas vividly to life for travelers of all interests.

-

Viking Walking Tour of Reykjavik: Explore Reykjavik on foot with a knowledgeable Viking guide, discovering historic sites from longhouses to the Althingi. This small-group tour blends city history, local folklore, and hidden gems, offering an intimate and engaging introduction to Iceland’s Viking heritage.

-

Caves of Hella Guided Tour: Descend into the mysterious man-made Caves of Hella, where Viking and possibly Celtic settlers left traces of life from centuries before Iceland’s official settlement. Your guide brings the underground world to life with stories of early settlers, local legends, and the caves’ fascinating history, creating a unique cultural adventure.

-

Scenic Viking Horseback Tour with Optional Transfer from Reykjavik: Ride Icelandic horses through the stunning Heidmork countryside while learning about the breed’s Viking origins and the surrounding landscapes. Small groups and optional transfers from Reykjavik ensure a personalized, scenic, and adventurous experience for both seasoned riders and beginners.

-

Reykjavik Folklore and Storytelling Experience: Step into a traditional Icelandic sitting room and listen to centuries-old sagas, folklore, and local legends shared by a skilled storyteller. This interactive evening connects visitors with Icelandic culture, revealing how stories shaped community life and preserving a direct link to the nation’s Viking past.

-

World in Words Exhibition in Reykjavik: Immerse yourself in Iceland’s literary heritage at World in Words, where medieval manuscripts, sagas, and poetry are presented in an engaging and interactive way. This exhibition highlights Iceland’s cultural history and the global influence of its literature, making it perfect for history and literature enthusiasts alike.

Additional Facts About Icelandic Vikings

This section provides additional insights about Icelandic Vikings, answering common questions and covering details not included in the main article. Learn more about their settlements, beliefs, daily life, language, and lasting legacy in Iceland.

This section provides additional insights about Icelandic Vikings, answering common questions and covering details not included in the main article. Learn more about their settlements, beliefs, daily life, language, and lasting legacy in Iceland.

Did Icelandic Vikings really wear horned helmets?

Vikings in Iceland did not wear horned helmets. The horned helmet image is a 19th-century invention popularized by opera costumes. Archaeological evidence shows that Icelandic Vikings wore simple conical or rounded metal helmets, or more commonly, leather caps.

How long did Vikings live in Iceland?

Vikings lived in Iceland from approximately 870 AD, when the first settlements were established, until 1262-1264 AD, when Iceland came under Norwegian rule. The cultural peak, known as the Saga Age, occurred roughly between 930 and 1030 AD.

Can Icelanders still speak Old Norse in Iceland?

Icelanders cannot speak Old Norse exactly, but modern Icelandic is the closest living language. Icelanders can read medieval sagas with modest help, something that is impossible in Norway, Denmark, or Sweden, where the languages evolved more dramatically.

What happened to Vikings in Iceland?

Vikings in Iceland gradually integrated into Christian society as Scandinavian kingdoms centralized power. Iceland converted peacefully in 999/1000 AD but maintained strong cultural continuity. Descendants of Viking settlers still farm the same valleys and read the same sagas their ancestors wrote.

Were Vikings in Iceland violent?

Vikings in Iceland were less violent than their Scandinavian counterparts. Geographic isolation limited raiding opportunities. Icelandic Viking society focused on farming, fishing, and trade, and disputes were usually resolved through the legal system (Thing assemblies), although feuds occasionally occurred.

The Legacy of Icelandic Vikings Today

Icelandic Vikings shaped the history of Iceland and left a lasting mark on its culture, law, and traditions. Visitors can experience this heritage through historic sites, sagas, museums, and festivals that bring the Viking Age to life. Learning about Iceland’s Viking past also reveals things to know about Icelanders today, including their pride in history, commitment to preserving language and culture, and resilience in a challenging environment.

Icelandic Vikings shaped the history of Iceland and left a lasting mark on its culture, law, and traditions. Visitors can experience this heritage through historic sites, sagas, museums, and festivals that bring the Viking Age to life. Learning about Iceland’s Viking past also reveals things to know about Icelanders today, including their pride in history, commitment to preserving language and culture, and resilience in a challenging environment.

Have you visited any of Iceland’s Viking sites or attended a Viking festival? Do you have a favorite saga, Viking figure, or historic site in Iceland? What part of Icelandic Viking history fascinated you the most? Share your experiences and interests in the comments below!