The Ultimate Guide to Downtown Reykjavik

What is the essence of central Reykjavík's allure? What districts make up downtown Reykjavík and how were they formed? What are some of the key characteristics of 101 Reykjavík, its landmarks, streets, and culture?

Welcome to downtown Reykjavík, the vibrant heart of Iceland’s capital city. While Reykjavík may be small compared to other world capitals, it offers a unique blend of culture, history, and modern charm that draws visitors from around the globe. From the colorful streets of 101 Reykjavík to its iconic landmarks like Hallgrímskirkja and Harpa, this area is full of surprises waiting to be explored.

Though Reykjavík is not a sprawling metropolis—with a population of under 250,000—this northernmost capital boasts an incredibly lively downtown rich in culture and history. Exploring it by booking a Reykjavik walking tour is a great way to discover the city's unique character, and securing your accommodation in Reykjavík ensures you’re right in the heart of this vibrant city's center.

Whether you’re interested in shopping along Laugavegur, enjoying local cuisine, or simply soaking in the city’s rich history, downtown Reykjavík has something for everyone. In this guide, we’ll take you through the must-see neighborhoods, hidden gems, and the best spots to experience the true essence of Reykjavík.

- See the Top 10 Things to Do in Reykjavík

- Discover the essential Secret Spots & Hidden Gems in Reykjavík

- Get to know the Best Shops in Reykjavík

The History and Evolution of Reykjavik

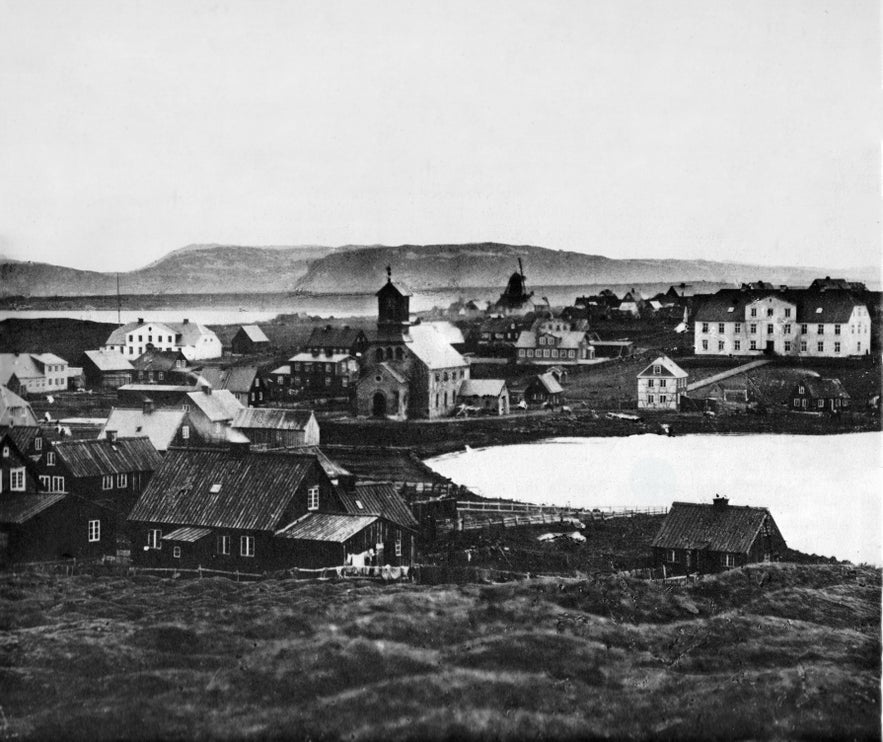

According to legend, Iceland's first settler, Ingólfur Arnarson, threw his high seat pillars into the sea upon first arriving at the island's shores in 870 AD and promised the gods to settle where they eventually drifted ashore.

It took Ingólfur and his men four years to locate the pillars and the following summer, they built their farmstead in the place he named Reykjavík, the Bay of Smoke.

Reykjavík, as we know it today, started growing around its harbor in the 18th Century, from where it stretched out to different cardinal directions. The Old Harbour and Kvosin are where it all began. There, commerce and trade were centralized, and consequently, these two neighborhoods constituted as Midbaerinn or the city center.

Through this territory, the canal of Laekjargata (Creek Street) served as the border between the trading center and the countryside.

The area west of the canal became known as Vesturbaer (West Town), while the eastern section was named Austurbaer (East Town). There, different neighborhoods arose and evolved.

The central port districts and Austurbær's Þingholtin became homes to merchants and business owners, while neighborhoods such as Grjotathorpid and Vesturbaer housed the working class.

Today, the city of Reykjavík has branched out much further than these fundamental distinctions suggest, therefore, these first suburbs are now considered central.

The old class divide between districts still lingers in some ways, but overall, the central city is home to people from all layers of society. However is there something that unifies the residents of central Reykjavik? If so, it might be something as trivial as a three-digit number.

- Read our more comprehensive article on the History of Reykjavík

- Read about the Music of Iceland here

101 Reykjavik

Photo from Private 2 Hour Reykjavik Sightseeing Adventure with Perlan, Grotta & Hallgrimskirkja

Photo from Private 2 Hour Reykjavik Sightseeing Adventure with Perlan, Grotta & Hallgrimskirkja

101 is the postal code that unifies the districts that make up the downtown area. Although the neighboring communities of codes 105 and 107 could be described as suburban, they are still easily accessible by foot from the center and integrally connected to its culture and history.

As with most urban areas around the world, the density of the population is greatest in this original part of the city. And for the past century, downtown Reykjavík has nursed its very own native; the people we lovingly refer to as Midbaejarrotta or the "Downtown Rat."

As nasty as that nickname might sound, it is in no way meant as an insult. Most of the central capital’s permanent residents wear the title with pride. While the center is home to an incredibly diverse flock that is impossible to classify as a whole, it has predominantly been known to harbor bohemians, artists, musicians, and the eternally young.

The video at the top of this article shows the trailer for Icelandic director Baltasar Kormákur’s debut feature film, adequately titled 101 Reykjavík. This darkly satirical urban tale tells of a typical downtown rat, Hlynur, a 30-year-old slacker who lives with his mother and spends most of his waking hours getting drunk at Kaffibarinn.

Although this borderline-depressed but beloved character in no way reflects all of the downtown’s residents, the stereotype he encapsulates is very much rooted in the real world; because of skyrocketing housing prices and service costs, the fly-by-night life is the reality of many inner-city dwellers.

- Check out what Wanda Star has to say about Rising Rent in Reykjavík

Although 101 Reykjavík has seen an influx of short-term rentals and rising rents in recent years, recent government regulations have sought to balance the needs of residents with the booming tourism industry. These efforts aim to preserve the character of the downtown area and ensure it remains accessible to locals.

While challenges remain for the average folk to afford to live in the center, for many of us rats, the suburbs are simply not an option. One will never want to leave the downtown if one has ever grown accustomed to the pleasure of calling it home.

The benefits of living in downtown Reykjavík extend far beyond the corrugated iron roof that's over one’s head. Living here grants the possibility of a lifestyle, not available anywhere else in the country.

Still, all complaints about the housing situation are eclipsed by the pleasures the central neighborhoods have to offer. So let’s move on and explore the different streets and districts that make up Reykjavík's city center.

Laugavegur, Bankastraeti & Austurstraeti

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by joseph knecht. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by joseph knecht. No edits made.

The Laugavegur shopping street is where it all begins. Connecting seamlessly with its sister streets Bankastraeti and Austurstraeti, this route is a pathway of local culture that every visitor to Iceland has to walk at least once; dotted with a myriad of shops, restaurants, galleries, cafés, bars, and homes, Laugavegur serves as the very artery of the capital.

What’s more, these establishments are often found in the same building. This means that a single house can host a restaurant that turns into a club come nightfall, while the upper levels might be residential apartments.

Photo by Nathan Dumlao

Photo by Nathan Dumlao

The street itself was originally commissioned by the Reykjavík Poverty Committee in 1885, as a means to combat unemployment. With the center of all businesses in Kvosin, Laugavegur served as the road by which one would reach the industrial harbor town from the countryside.

Consequently, the locals seized the opportunity and started setting up shops and services along the route to catch potential customers before they reached the larger stores by the seaside.

- See also: Nightlife in Reykjavík

- See also: Laugavegur Travel Guide

But when the U.S. Armed Forces occupied Iceland at the end of World War II, they created a demand for nightlife and entertainment—and soon enough, bars started popping up downtown, and the locals got to know the benefits of drinking, dancing, and eating out.

Where Laugavegur meets Skólavordustígur, Bankastraeti (Bank Street) begins. Its namesake is The National Bank of Iceland (Landsbankinn) which began its operations at Bankastræti 3 in 1886.

Today, Reykjavík’s business district is located in Borgartun, while Bankastræti serves as a natural extension of Laugavegur, consisting mostly of shops and restaurants.

- See also: The Best Restaurants in Reykjavík

Past the intersection of Laekjargata, the old canal street, Austurstraeti connects the center artery to Kvosin and the Old Harbour. The street contains most of Reykjavík’s different architectural styles—with everything from the old timber houses of the merchant era and the country’s first concrete buildings to large modern structures of glass and steel.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Jóhann Heiðar Árnason. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Jóhann Heiðar Árnason. No edits made.

The name of Guðjón Samúelsson will come up many times throughout this guide, as he is widely considered Iceland’s most renowned architect, having designed many of Central Reykjavík's most iconic buildings.

You’ll find one of Samuelsson’s earliest works at Austurstraeti 16. The largest building in Reykjavík at the time of its construction in 1916 and has served as the headquarters for both The National Bank and the Icelandic Freemasons.

Today, the restaurant Apotekið is stationed on the ground floor of this grand concrete structure, taking its name from the city pharmacy that operated there from 1930-1999. Today, the spot is one of the finest wining and dining locations in Reykjavik.

Another beautiful building of interest is Hressingarskalinn often referred to as "Hresso" at Austurstræti 20. A newly renovated restaurant and a bar, this timber lodge from the early 1800s used to be the home of county depute Arni Thorsteinsson. The residential garden, utilized by the restaurant on sunny days and sometimes the venue of live music, is home to sizable trees planted by Thorsteinsson himself over a century ago.

Hverfisgata & Skulagata

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Vera de Kok. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Vera de Kok. No edits made.

Hverfisgata is one of Reykjavík’s key streets, stretching from the Hlemmur food hall down to Laekjartorg Square. Although it runs parallel to the main shopping street, Laugavegur, and is home to several landmark buildings, Hverfisgata was often overlooked by locals due to its neglected and somewhat sketchy reputation. For years, many people hesitated to venture below Laugavegur, but recently, the street has undergone a vibrant transformation, making it a must-see destination full of hidden gems and revived charm.

- See also: Time in Iceland | A Land of Here and Now

- See also: Hverfisgata Street Travel Guide

Hverfisgata's history dates back to 1802 when the foundation of its first abode, Skuggi (Shadow), was laid. Around this house, others were soon built, and the resulting neighborhood became known as Skuggahverfid (the Shadow Neighbourhood).

Photo from piqsels

Photo from piqsels

Until 2010, the district's roads and houses were in desperate need of repair and most of the establishments found were a couple of seedy Adult Stores. Today, however, you'll find the newly paved street dotted with popular clothing stores, elegant restaurants, charming cafés and inviting bistros.

Hverfisgata deserved this long-awaited makeover, given its array of marvelous and classical buildings. The dominant example would be the National Theatre, designed, again, by Guðjón Samúelsson.

- See also: Top 21 Vegan & Vegetarian Restaurants in Reykjavík

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Jóhann Heiðar Árnason. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Jóhann Heiðar Árnason. No edits made.

Other buildings of interest include Safnahúsið—an exhibition space constructed in 1906 by Danish architect Johannes Nielsen—and the Danish Embassy, built-in 1913 by local merchant brothers Sturla and Friðrik Jónsson.

There's plenty more in the area to enjoy than history and grand old houses. At Hverfisgata 12, you'll find Rontgen, a local favorite bar and nightclub, located in a beautiful four-story building from 1910. As you groove on the dance floor during a good night out, you might notice the floorboards joining in—sometimes it feels like this old building is dancing along with you, a testament to how it has stood the test of time.

Walk a bit further, and you'll reach the independent cinema house Bíó Paradís—the successor of movie theatre Regnboginn which ran from 1977. In Hverfisgata You can enjoy a meal at the amazing Indian restaurant Austur-India Felagid, before catching a live jazz show at KEX Hostel which is housed in a renovated biscuit factory at Skúlagata 28.

Walk a bit further, and you'll reach the independent cinema house Bíó Paradís—the successor of movie theatre Regnboginn which ran from 1977. In Hverfisgata You can enjoy a meal at the amazing Indian restaurant Austur-India Felagid, before catching a live jazz show at KEX Hostel which is housed in a renovated biscuit factory at Skúlagata 28.

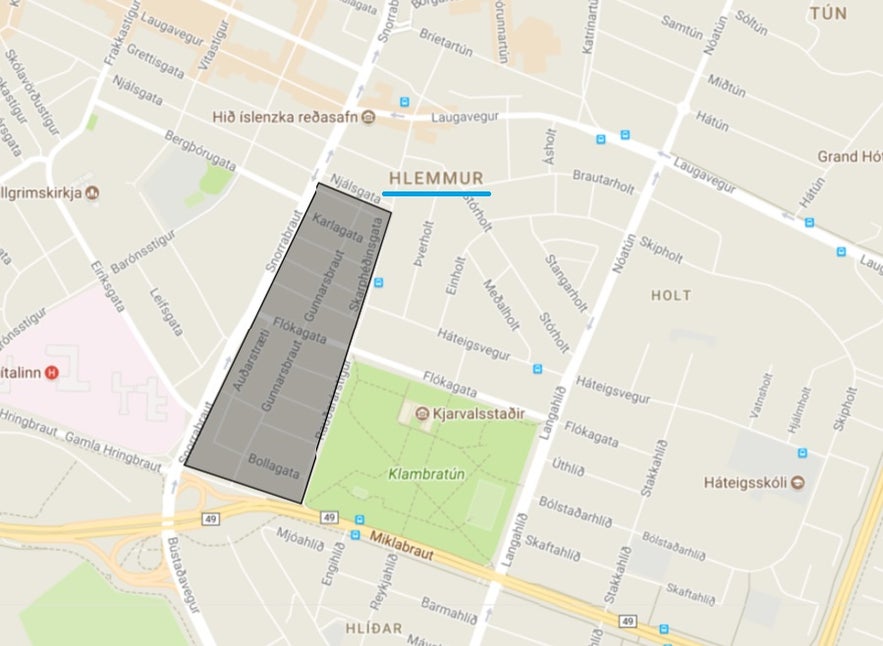

Hlemmur & Nordurmyri

Let’s move onto Reykjavík 105, to the edge of downtown. Hlemmur, Reykjavík's central bus terminal, marks the spot where many people feel Laugavegur unofficially ends, although the street technically reaches an additional kilometer east.

For decades, Hlemmur served as a second home to Reykjavík's outcasts. Because of the terminal’s central location, it sheltered those with nowhere else to go and in the early 1980s, the spot also functioned as a haven for the young runaways of the punk generation.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Helgi Halldórsson. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Helgi Halldórsson. No edits made.

For decades, Hlemmur was a cultural hub that seemed stuck in time—run-down and frequented by the city's marginalized communities. However, in 2017, Hlemmur was transformed into Hlemmur Matholl, a food hall that has since become a beloved destination for locals and visitors, offering a variety of culinary delights in this beautifully restored space.

Hlemmur is named after a small arch that used to bridge Raudara (Red River) in old Reykjavík. The river is no longer there, but follow Raudararstigur (Red River Road) past the favored local record store Lucky Records. Just to your right, you’ll find Norðurmyri, one of the most charming neighborhoods in the downtown area.

Hlemmur is named after a small arch that used to bridge Raudara (Red River) in old Reykjavík. The river is no longer there, but follow Raudararstigur (Red River Road) past the favored local record store Lucky Records. Just to your right, you’ll find Norðurmyri, one of the most charming neighborhoods in the downtown area.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Jóhann Heiðar Árnason. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Jóhann Heiðar Árnason. No edits made.

Norðurmýri is something of an urban oasis, where stone houses and fenced gardens come together to create central suburbia, sometimes referred to as the "Brooklyn" of downtown Reykjavík. The name of the precinct, marked by Miklabraut in the South and Snorrabraut in the West, translates to ‘Swamp of the North’, referring to the old swampland that used to cover the area. Most of the houses here were built in the 1930s, and the streets are named after characters from the Icelandic Sagas Njala and Laxdaela, as well as the Book of Settlement (Landnámabók).

All the houses' gardens face south, providing optimal sunshine and ample opportunity for residents to grow various plants for harvesting or beautification.

- Learn more about the Sagas here: Icelandic Literature for Beginners

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Gary J. Wood. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Gary J. Wood. No edits made.

Throughout the years, the neighborhood has been known to harbor an abundance of artists, scholars, and musicians. Nordurmyri occasionally hosts lively block parties, where the streets are decorated, and live music, markets, and workshops pop up on a selected summer’s day.

Skolavordustigur & Thingholt

One of the most iconic landmarks in Reykjavik is undoubtedly Hallgrímskirkja Church, a monumental triumph of Icelandic architecture perched atop Skolavorduhaed Hill. The hill's name predates the church by about two hundred years. In front of Hallgrimskirkja stands a statue of the explorer Leifur Eiriksson, marking the spot where a stone tower known as Skolavardan (the School Cairn) once stood—a monument built by students in the 1700s as part of a homecoming ritual.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Gerd Eichmann. No edits were made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Gerd Eichmann. No edits were made.

The tower’s latest rendition, constructed in 1868 and commissioned by Governor Arni Thorsteinsson, could historically be called Reykjavík’s very first man-made landmark.

The pathway leading up to the tower became known as Skolavordustigur (School Cairn Road), but the tower was demolished when Alþingi, Iceland's legislative body, saw its 1000th anniversary. Then, the statue of explorer Leifur Eiríksson—a gift from the United States government—permanently took its place.

Today, Skólavörðustígur is one of the most traversed streets in the city, boasting numerous restaurants, boutiques, design shops, and cafés. Some of the street's most ancient buildings still stand there, such as Hegningarhúsið, Iceland's oldest prison.

At the base of Skólavörðustígur, you'll find the vibrant Rainbow Road, a colorful stretch of pavement painted to celebrate diversity and inclusivity. This iconic pathway has become a beloved symbol of Reykjavík’s open-minded spirit, drawing both locals and visitors to stroll along its bright colors, adding a splash of joy to one of the city’s most historic streets.

At the base of Skólavörðustígur, you'll find the vibrant Rainbow Road, a colorful stretch of pavement painted to celebrate diversity and inclusivity. This iconic pathway has become a beloved symbol of Reykjavík’s open-minded spirit, drawing both locals and visitors to stroll along its bright colors, adding a splash of joy to one of the city’s most historic streets.

- See also: Skolavordustigur Street Travel Guide

- Se also: The Ultimate Guide to Gay Iceland | LGBT+ History, Rights and Culture

To the left of Skólavörðuhæð stretches the residential neighborhood Þingholtin, dotted with old and colorful houses of timber and corrugated iron. Take a stroll down the district's main road Midstraeti and behold an entire block of perfectly preserved 19th Century houses that have been home to many of Iceland's most distinguished intellectuals and poets.

To the left of Skólavörðuhæð stretches the residential neighborhood Þingholtin, dotted with old and colorful houses of timber and corrugated iron. Take a stroll down the district's main road Midstraeti and behold an entire block of perfectly preserved 19th Century houses that have been home to many of Iceland's most distinguished intellectuals and poets.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by HerbertG. No edits made.

The area's main attraction is arguably Menntaskolinn í Reykjavik, the city’s oldest junior college. The building was erected in 1846 but the school itself traces its origins back as early as 1056.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Carpfish. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Carpfish. No edits made.

Last but not least, you'd be well advised to visit the Einar Jónsson Sculpture Garden, an inner-city gem overlooked by many of Reykjavík's visitors. Einar Jónsson is Iceland’s most celebrated sculptor, having produced countless masterpieces such as the Ingólfur Arnarson statue on Arnarholl Hill.

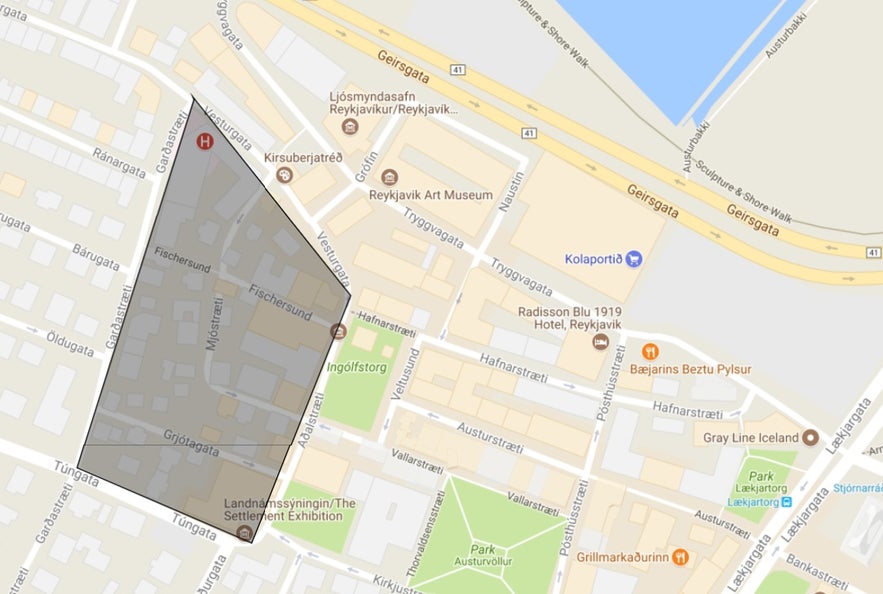

Grjotathorpid & Kvosin

Grjotathorpid is home to some of the oldest houses in the capital. Because it was constructed before the existence of a city planning committee, the neighborhood is composed of crisscrossing streets and randomly placed houses—this, however, only adds to its charm and appeal.

As it happened with the Skuggi Farm and the Skuggahverfi District―having begun to develop around a small farmstead known as Grjotid (The Rock) in the middle of the 18th century, the area eventually became known as Grjotathorpid (Rock Village).

A captivating landmark in the district is Unuhús, located at Garðastræti 15. The house was named after Una Gisladóttir, a revered friend to the poor who ran a bargain-priced guesthouse at the location.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Una's house had become a cultural center, with regulars including writers Þórbergur Þórðarson and Halldór Laxness who would become Iceland's first and only Nobel laureate in literature.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Friedrich Magnusson. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Friedrich Magnusson. No edits made.

Grjotathorpid begins by Adalstraeti (Main Street), which also marks the outset of Kvosin. At Aðalstræti 10, the oldest house in central Reykjavík still stands, constructed in 1762 as part of Sheriff Skuli Magnusson's industrialization efforts.

In 2001 a 10th Century Viking longhouse was unearthed at Aðalstræti 16 and is now open to the public as the centrepiece of The Settlement Exhibition.

Since the development of Kvosin constitutes both the beginning of Iceland's settlement and Reykjavík's industrialization, the district is known as the birthplace of Reykjavík.

Kvosin is bordered by Aðalstræti, Lækjargata and Lake Tjörnin. Today, Tjörnin serves as one of the most scenic spots in the central capital. All around this idyllic bird colony, there's plenty of beauty to behold—from the old Scandinavian lake homes that dot the eastern shore on Tjarnargata (Pond Street) to the lush public gardens of Hljómskálagarður and Hallargarður.

- See also: Tjörnin | The Pond in Reykjavík

Additionally, you'll find several museums encircling the lake, including the National Museum and the Reykjavík Art Museum. Furthermore, Reykjavík's City Hall was constructed on a landfill in Tjörnin in 1992; and apart from being the arena in which the capital's politicians stage their dramas, City Hall is also home to Reykjavík's official Tourist Information Centre.

- Explore the many Museums and Exhibitions of Reykjavik here!

- Get unlimited access to the city's many museums with the Reykjavík City Card

The monumental City Hall building, designed by local architecture firm Studio Granda, is constructed in such a manner that it appears to rise directly from the surface of the water.

Harpa & The Old Harbour

For a nation historically dependent on fishing, the charming and colorful Old Harbor, known to the locals as Reykjavikurhofn, was originally a natural inlet that became enveloped in a maze of wooden docks over time.

These, however, were only suited for smaller vessels and larger ships had to make anchors far away from the shoreline.

The construction of a proper harbor was a matter of social debate for decades, but the argument was driven home after a great storm destroyed a large group of ships anchored offshore in 1910. Following the disaster, the government agreed to fund the building of a harbor and in 1913, large ships could finally dock in Reykjavík.

The building of the new and improved docks was the greatest industrial project the country had seen. The Reykjavík Harbour would function as the capital's official shipping port until the 1960s when the larger Sundahöfn harbor was constructed.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Reykholt. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Reykholt. No edits made.

For decades after this shift, the Old Harbour was primarily used by independent fishers and boat owners, as well as serving as the operational center for the Coast Guard of Iceland.

Today, the harbor is teeming with life. At Port Sudurbugt, vibrantly blue industrial sheds from the 1930s now house seafood restaurants and cafés, many cultural attractions, and whale-watching tours that set out daily from the docks.

- See also: Whale Watching in Iceland

- See also: The Ultimate Guide to Cultural Tours in Iceland

You'd be well advised to visit the Reykjavík Maritime Museum at Grandagarður, which is a fantastic way to become versed in the importance of the docks and how the Icelandic nation was shaped by the ocean.

But there's one development above all others that constitutes the harbor's greatest makeover since its original construction.

Completed in 2011, Harpa Concert Hall and Conference Centre remains one of Reykjavík's most iconic landmarks. Designed by local artist Ólafur Elíasson in collaboration with Danish firm Henning Larsen Architects, Harpa continues to be a centrepiece of the city’s cultural life, hosting everything from concerts and conferences to exhibitions and festivals.

In addition to the grand concert hall, original plans for the area included a World Trade Centre, a hotel, apartment complexes, shops and a large car park. The 2008 financial crisis, however, put a stop to these ambitious and costly procedures.

Be that as it may, the idea of building a proper concert hall for the nation had been circling since the 1880s, so the Icelandic government (broke or not) decided to finance the completion of the project.

The superstructure consequently got built, serving as a final visual reminder of the boom before the crash. That is not to say the Icelandic people detest or disapprove of the building. On the contrary—the voices that opposed to spending money on the project became noticeably quiet when the phenomenal result saw the light of day.

Photo from WIkimedia, Creative Commons, by Ivan Sabljak. No edits made.

Photo from WIkimedia, Creative Commons, by Ivan Sabljak. No edits made.

The building boasts a facade of over 700 glass panels designed by the genius geometrist Einar Þorsteinn Ásgeirsson. Each panel has its unique shape, as well as being installed with LED lights that offer spectacular light shows on dark winter nights.

Today, Harpan hosts the Icelandic Symphony Orchestra and offices of the Icelandic Opera, as well as an array of exhibitions, concerts, and cultural events.

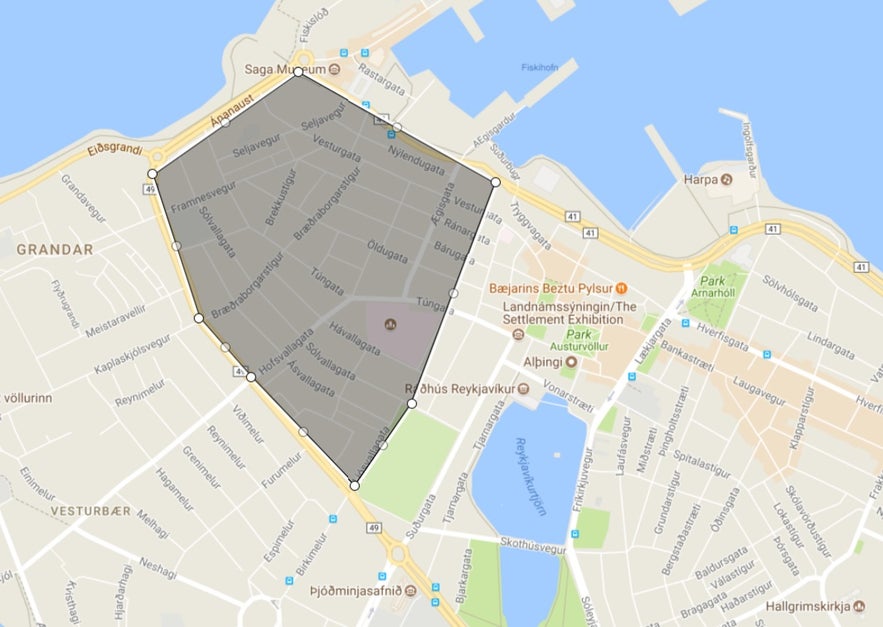

Gamli Vesturbaer & Holavallagardur

Vesturbaer is a large district in Reykjavík that stretches out from the center to the outskirts of the Seltjarnarnes township. The name of the region translates to West Town, while the area north of Hringbraut Road that belongs to postal code 101 is known as Gamli Vesturbærinn (Old West Town).

Much like Grjotathorpið, the district historically belonged to the lower working classes, but today, such class distinctions are mostly gone. Vesturbær counts as a suburban part of 101 Reykjavík and an excellent place to call home.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Kasuarer. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Kasuarer. No edits made.

A pleasant spot to visit in the area is Landakot, a lush green hill rich with Iceland's Catholic history. Which started in 1864 when Catholic priests from France had a small chapel built next to their farm. A few years later, the chapel was replaced by a wooden church.

Then after World War I, the Catholic Church in Iceland felt the need for a greater house of worship. Architect Guðjón Samúelsson was yet again deemed the right person for the job, resulting in the glorious new-gothic construction of Landakotskirkja in 1929.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Jon Gretarsson. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Jon Gretarsson. No edits made.

Another monument of note in the area is Landakotsspitali Hospital, built in 1902 at a time, when the city was in dire need of a new health institution, but all out of funds, so the project got backed by the Catholics with financial support from Europe.

The state eventually took over administrating the hospital with the establishment of Landsspítalinn (The National University Hospital of Iceland) in 1930.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Jon Gretarsson. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Jon Gretarsson. No edits made.

Nesting between Landakot and Lake Tjörnin you'll find a particularly favoured spot in the central capital. Holavallagarður is a 19th-century cemetery, rightfully voted as one of Europe's loveliest by National Geographic in 2014.

The park constitutes one of the city’s most enchanting scenes, where tall and barren trees of birch, willow, and spruce surround narrow pathways and ashen headstones.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Christian Bickel. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Christian Bickel. No edits made.

The permanent residents of this urban thicket include Jón Sigurðsson, leader of Iceland’s independence movement; Hannes Hafsteinn, poet and political leader; and Bríet Bjarnhéðinsdóttir, the forerunner of women’s suffrage in Iceland.

Take a romantic stroll through this bewitching old graveyard and notice how the bustle of the capital stifles down, as you travel back in time amongst some of the most fondly remembered residents of Reykjavík City.

Given 101 Reykjavík's settlement history, trading post origins, monumental dwellings, and cultural allure, it’s no wonder that the downtown area ranks as the most highly favored domicile of the Icelandic nation.

Despite minor recurrences of suburban flights throughout the years, businesses and individuals tend to choose the walkable city center as their ideal location. The area offers a less car-dependent, more urban lifestyle, that attracts more than just the young.

The downtown districts might be under pressure for the time being, given the incredible amount of visitors, but that also results in the capital becoming more vibrant than ever before.

When visiting the city center, you'd be well advised to acquaint yourself with the local culture. Favour local businesses over international chains. Get to know the rats. Engage in the environment at hand, and not only will you be supporting the local way of life—you’ll obtain a more authentic and gratifying experience throughout your stay.

101 Reykjavík is a unique and enchanting urban paradise, where wonders await at every corner. Let’s make sure it stays that way by taking care of it together.

Did you enjoy our guide to the city center of Reykjavík? What are your favorite spots and districts in postal code 101? Tell us what you think in the comments box below!

Weitere interessante Artikel

Die besten Restaurants in Reykjavik

Welches sind die besten Feinschmecker-Restaurants in Reykjavik? Wo kannst du die traditionelle isländische Küche erleben? Welches sind die besten internationalen Restaurants in der Stadt? Für jedes...WeiterlesenSehenswürdigkeiten in Reykjavik | Der ultimative Guide

Tauche ein in die lebhafte Kultur der isländischen Hauptstadt und informiere dich über die besten Sehenswürdigkeiten in Reykjavík. Welche sind die symbolträchtigsten Orte der Stadt? Wo findet sich d...WeiterlesenDie 13 besten preiswerten Dinge, die es in Reykjavik zu tun gibt

Hier erfährst du, was du in Reykjavik kostenlos und günstig unternehmen kannst und was es nachts zu tun gibt. Lebendige Straßen und eine blühende Kultur inmitten großartiger Landschaften kennzeichnen...Weiterlesen

Lade Islands größten Reisemarktplatz auf dein Handy herunter, um deine gesamte Reise an einem Ort zu verwalten

Scanne diesen QR-Code mit der Kamera deines Handys und klicke auf den angezeigten Link, um Islands größten Reisemarktplatz in deine Tasche zu laden. Füge deine Telefonnummer oder E-Mail-Adresse hinzu, um eine SMS oder E-Mail mit dem Download-Link zu erhalten.