Iceland is home to some of the most active volcanoes in the world, and the country's nature and culture bear marks of this volcanic activity. The North Atlantic island was born out of the seafloor spreading along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the boundary between the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates, some 24 million years ago.

Strewn across the country, many of Iceland's volcanoes can be seen when exploring the island by renting a car and taking on the Ring Road or on several fantastic self-drive tours. You can explore volcanoes, craters, and the aftermath of eruptions on one of the many exciting volcano tours. If you need a place to stay while visiting, make sure to book accommodation on Iceland's largest travel platform.

Why You Can Trust Our Content

Guide to Iceland is the most trusted travel platform in Iceland, helping millions of visitors each year. All our content is written and reviewed by local experts who are deeply familiar with Iceland. You can count on us for accurate, up-to-date, and trustworthy travel advice.

Over the centuries, countless eruptions have molded Iceland's landscape, influenced its climate, and shaped its culture. From colossal eruptions that may have sparked revolutions overseas to picturesque effusive eruptions attracting visitors from around the globe, these geological occurrences have had local and global impacts.

In this article, we will delve into the rich volcanic history of Iceland. While the list is not exhaustive, these are some of the most noteworthy eruptions that have shaped the island's fiery identity.

- See more: A Complete Guide to Iceland's Volcanoes

- See also: Volcanic Eruptions on the Reykjanes Peninsula in Iceland - A Complete Timeline

Types of Eruptions in Iceland

Before diving into the inferno, brushing up on some of the different types of volcanic eruptions you might find in Iceland might be helpful. The island's unique geological position gives rise to a diverse range of volcanic activity, which includes the following:

Before diving into the inferno, brushing up on some of the different types of volcanic eruptions you might find in Iceland might be helpful. The island's unique geological position gives rise to a diverse range of volcanic activity, which includes the following:

-

Effusive Eruptions: This type of eruption is characterized by the outpouring of lava onto the ground. The lava tends to be relatively low in viscosity, meaning it can flow easily across the landscape. While these eruptions can create vast lava fields and cause significant changes to the local landscape, they are generally less explosive and less dangerous to humans than some other types of eruptions.

-

Explosive Eruptions: These eruptions are violent and can eject large amounts of material into the atmosphere. This is often due to high gas content and/or interaction with water (such as a glacier), which can cause the magma to explode when it reaches the surface.

-

Phreatomagmatic Eruptions: This type of eruption occurs when water comes into contact with magma, leading to rapid cooling and explosive fragmentation of the magma into fine ash.

-

Fissure Eruptions: Iceland is also known for its fissure eruptions, which occur along cracks or rifts in the Earth's crust. These can be either explosive or effusive, producing long curtains of fire as magma erupts along the fissure.

-

Plinian Eruptions: Plinian eruptions are characterized by the ejection of large amounts of pumice and ash into the atmosphere, forming a large eruption column.

Each type of eruption has different potential impacts, including the production of lava flows, ash clouds, pyroclastic flows, and other hazards. The kind of eruption that occurs depends on several factors, including the composition of the magma, the presence of water, and the configuration of the volcanic vent.

What is Tephra?

A term you'll encounter on this list is tephra, which refers to the fragmented material ejected during a volcanic eruption. It is a collective term encompassing a range of volcanic particles, including ash, lapilli, and volcanic blocks.

The different composition of tephra can significantly impact local environments and human populations. Ashfall can disrupt air travel, contaminate water sources, and pose respiratory hazards.

Additionally, tephra deposits can bury landscapes, alter drainage patterns, and affect ecosystems.

Historical Eruptions in Iceland

While volcanic activity has been present in Iceland since the beginning, we'll start our list with the eruptions following the settlement of Iceland in the 9th century up until the 20th century.

Hekla (1104)

Hekla is one of Iceland's best-known volcanoes and has been so for a long time. In the Middle Ages, it was a common belief in Europe that Hekla was the entrance to hell itself. This infernal reputation likely began with Hekla's most powerful eruption in 1104.

Hekla is one of Iceland's best-known volcanoes and has been so for a long time. In the Middle Ages, it was a common belief in Europe that Hekla was the entrance to hell itself. This infernal reputation likely began with Hekla's most powerful eruption in 1104.

As this was Hekla's first eruption since settlement, it made quite an impression on the Icelandic people. The volcano erupted without warning, spewing out millions of tons of tephra. The damage was enormous, destroying a prominent settlement nearby and causing widespread harm to agriculture and livestock.

Hekla has gone off several times since, but never with the same amount of power and destruction as this explosive eruption. It remains one of Iceland's most unpredictable volcanoes to this day.

Its infernal reputation remains on this 16th-century map of Iceland by famed cartographer Abraham Ortelius as seen above, depicted as an everlasting firestorm. The Latin translates to "Hekla, forever condemned to storms and snow, spewing stones with a horrible noise."

You can explore the lava fields and craters of the volcano on this epic 12-hour Super Jeep tour to Landmannalaugar and Hekla.

The Reykjanes Fires (1210-1240)

The Reykjanes peninsula experienced a series of eruptions early in the 13th century, which have since been called the Reykjanes Fires. They began in the sea off the southwestern tip of the peninsula in 1210, and eruptions would happen every few years until 1240.

The Reykjanes peninsula experienced a series of eruptions early in the 13th century, which have since been called the Reykjanes Fires. They began in the sea off the southwestern tip of the peninsula in 1210, and eruptions would happen every few years until 1240.

The most powerful of these eruptions happened in 1226 when a violent eruption spewed ash and lava all over the Reykjanes peninsula. Written records describe the conditions as "darkness during the daytime," and the following winter was a so-called "sand winter," a term used to describe the devastating effects of the volcanic ash on livestock and farming.

Many lava fields that characterize the Reykjanes peninsula were created during the Reykjanes Fires. After this series of eruptions, the volcanic activity in the area would remain quiet for nearly 800 years, until only recently.

Today, the rugged allure of the peninsula attracts many visitors to experience the harsh beauty of the area on one of many available Reykjanes tours.

Oraefajokull (1362)

One of the most terrifying eruptions in Icelandic history happened in 1362 when Oraefajokull erupted in a steam-blast eruption with catastrophic effects. The volume of the eruption was about ten cubic kilometers, which is about four times more than the Hekla eruption in 1104.

One of the most terrifying eruptions in Icelandic history happened in 1362 when Oraefajokull erupted in a steam-blast eruption with catastrophic effects. The volume of the eruption was about ten cubic kilometers, which is about four times more than the Hekla eruption in 1104.

The surrounding region, including 20-24 farms, was laid to waste, killing most, if not all, inhabitants and livestock. Most of the destruction was not caused by lava or tephra but because of glacial outburst floods, which resulted from the eruption, sweeping down the valleys with frightening speed and force.

The peak of Oraefajokull is Hvannadalshnukur, the highest peak in all of Iceland, standing at a height of 6952 feet (2110 meters). This area can be explored on an epic helicopter tour of Oraefajokull.

Oraefajokull is thankfully not one of Iceland's most active volcanoes, as the few eruptions that do occur there tend to be devastating.

Veidivotn (1477)

Veidivotn is a cluster of lakes located in the Highlands of Iceland. Many of these lakes are volcanic craters created during a gigantic explosive eruption in 1477. A 41-mile (67 kilometers) long fissure running along the area's middle erupted. As the lava flowed over the very wet land, powerful steam explosions created many craters that later became lakes.

Before the eruption, the lakes in the area were very few, but today they are upwards of fifty. Today, Veidivotn is a natural oasis in the Icelandic Highlands, home to over 57 species of birds and home to one of the oldest stocks of trout in Europe. This makes Veidivotn a popular spot for fishing, as is evident by the name, which translates directly to "Fishing Lakes."

Katla (1625)

Katla is one of Iceland's most powerful and explosive volcanoes, connected to the same volcanic system as the Eyjafjallajokull volcano. The volcano sits beneath the Myrdalsjokull glacier in South Iceland and is notorious for its vast ash clouds and catastrophic glacial outburst floods when it erupts.

In 1625, a huge eruption began in Katla after several earthquakes. The eruption caused a glacial outburst flood, which destroyed 18 farms in the nearby region. Despite the widespread destruction, the eruption only lasted twelve days.

This breathtaking area can be reached on a Super Jeep tour of Katla, starting from the village of Vik. This will take you inside an ice cave that is hidden beneath the glacier that covers up this frightful volcano.

The Myvatn Fires (1724-1729)

The Myvatn fires, known as "Myvatnseldar" in Icelandic, refer to a series of volcanic eruptions that occurred in the Myvatn region of northeast Iceland between 1724-1729. This series of eruptions came from the Krafla volcanic system, including the Krafla volcano itself and a large area of the associated fissure swarm.

The effects of these eruptions were quite impactful. Large volumes of lava and tephra were ejected, destroying several farms in the region, although there were no recorded human deaths. The Myvatn fires also created or enlarged several of the craters around Lake Myvatn, which is today one of Iceland's most picturesque locations.

The eruptions also dramatically affected the local landscape, creating a diverse and starkly beautiful terrain that includes lava fields, volcanic craters, and hot springs, which continue to draw visitors to the region. You can experience them yourself on one of the fantastic Myvatn tours available or take a dip in serene Earth Lagoon by the lake.

- Read more: The Ultimate Guide to Lake Myvatn

Laki (1783)

The Laki eruption in 1783 is one of recorded history's deadliest and most powerful eruptions. The phreatomagmatic eruption lasted for eight months, releasing an estimated 14.7 km³ of basalt lava and huge amounts of toxic gases, including sulfur dioxide and hydrogen fluoride, which resulted in a haze that spread across Iceland and over to mainland Europe.

The Laki eruption in 1783 is one of recorded history's deadliest and most powerful eruptions. The phreatomagmatic eruption lasted for eight months, releasing an estimated 14.7 km³ of basalt lava and huge amounts of toxic gases, including sulfur dioxide and hydrogen fluoride, which resulted in a haze that spread across Iceland and over to mainland Europe.

In Iceland, the consequences were devastating. It is estimated that about 10,000 people, or roughly 20-25% of the population, died due to famine and fluorine poisoning caused by the ash fallout. The eruption also significantly impacted livestock, killing around 80% of the sheep, 50% of cattle, and 50% of horses, which further contributed to the famine. The details of the eruption are masterfully chronicled in the works of reverend Jon Steingrimsson, who received the moniker "the fire cleric" because of his writings.

Furthermore, the event had worldwide effects. Crops were destroyed and livestock depleted across the continent, with effects also being felt in Asia, North Africa, and Asia; it caused a particularly devasting famine in Egypt. Some reports suggest it may have contributed to several years of extreme weather in Europe, which may have negatively affected grain production, which may, in turn, have indirectly led to social unrest in France and influenced the French Revolution in 1789(!)

The eruption's aftermath is still visible today in Lakagigar - a spectacular row of craters in the Highlands. Jump into a super jeep and see them yourself on an epic 8-hour tour of Lakagigar Craters & Fjadrargljufur Canyon.

Askja (1875)

Askja is the name of an active volcano and a lake-filled caldera in the central Highlands of Iceland. The volcano itself was not really known until 1875, when it erupted with enormous force, the effects of which spread far into Europe.

Askja is the name of an active volcano and a lake-filled caldera in the central Highlands of Iceland. The volcano itself was not really known until 1875, when it erupted with enormous force, the effects of which spread far into Europe.

Contemporary descriptions of the eruption are downright cataclysmic. This plinian eruption began with the rising of a terrifying plume of ash that spread over the East of Iceland. Thunder and lightning raged in the sky as visibility was next to none. Rocks the size of tennis balls were still warm when they crashed into the ground tens of miles away from the eruption site.

This devastated people living in the East of Iceland, as livestock and crops wilted and died. This forced a major wave of emigration from the country to North America, with the majority of Icelanders settling in the Canadian province of Manitoba and the US state of Minnesota.

Lake Oskjuvatn was created in the eruption and is Iceland's second-deepest lake. It was considered the deepest until Jokulsarlon was measured at 918 feet (280 meters).

- See also: How to visit Askja in the Highlands

20th-Century Eruptions in Iceland

As Iceland entered the 20th century, technological advancements allowed the country to better understand the seismic and volcanic forces at play during eruptions.

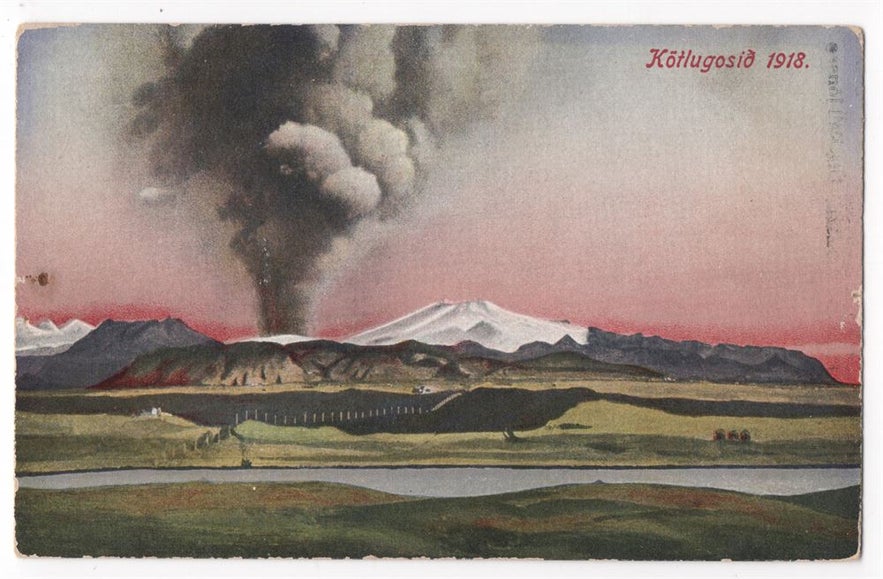

Katla (1918)

Since Iceland was settled, Katla has erupted 21 times, according to estimations. The last real eruption in Katla happened in 1918 when the volcano roused from its slumber once more.

Since Iceland was settled, Katla has erupted 21 times, according to estimations. The last real eruption in Katla happened in 1918 when the volcano roused from its slumber once more.

As usual of an eruption in Katla, most of the damage was done by subsequent outburst floods. It is mostly due to coincidence that the eruption didn't claim any lives, as a number of farmers that were supposed to be herding sheep in the area had been delayed by a week. If the herding had been on schedule, many would likely have perished in the eruption.

The eruptions in Katla are rarely more than a century apart. Today there have been 105 years since Katla last erupted, making the volcano's rumblings ever more ominous.

Surtsey (1963-67)

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Howell Williams.

The island of Surtsey was formed through volcanic eruptions that took place from 1963 to 1967. Named after Surtr, a fire giant from Norse mythology, the eruption of Surtsey granted scientists a rare opportunity to witness the birth of an island in real-time.

During the eruptions, tephra (rock fragments and particles ejected by a volcanic eruption), lava, and volcanic gases were released, forming the island. Initially, the island was about 2.7 square kilometers in size. However, since the end of the eruptions in 1967, the island has been gradually eroding due to the action of waves, and as of 2021, its size is approximately 1.3 square kilometers.

Biological examination began almost immediately after the eruptions ceased. Seeds carried by ocean currents, wind, and birds began to establish life on Surtsey. As of now, the island supports a variety of plant life and is home to various bird species. In 2008, Surtsey was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is considered the youngest land mass on Earth. As part of the Vestmannaeyjar (Westman Islands) archipelago, Surtsey can be seen from afar while cruising the area on a scenic 1-hour small island boat tour in Vestmannaeyjar.

Westman Islands (1973)

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Tom Simkin.

The inhabitants of the Westman Islands, or Vestmannaeyjar, had a rude awakening in the early hours of January 23, 1973. The volcano Eldfell, located on the isle of Heimaey, had erupted. This came as a surprise as there had been no significant seismic activity prior that would have indicated an imminent eruption.

The eruption caused a major crisis for the island's residents. However, thanks to a well-constructed emergency plan, everyone was safely evacuated within a few hours, and only one person lost their life as a result of this tragic event.

The eruption lasted until July of the same year, during which lava and ash significantly changed the island's landscape. Around 400 homes, about one-third of the houses in the town, were buried under lava and ash, and the island's size increased by about 2.24 square kilometers due to new lava fields.

An incredible method to minimize damage during the eruption involved cooling the advancing lava flow with seawater. Icelandic rescue teams and the US military worked together to prevent the lava from closing the island's harbor, which is crucial for the fishing industry - the primary source of income for the inhabitants.

Photo from Wikimedia Creative Commons by Christian Bickel

After the eruption, a large-scale excavation and rebuilding effort took place, and most of the island's residents eventually returned. The eruption and its aftermath had a profound impact on the island's community and left a mark on the landscape, as can be seen in the Eldheimar volcano museum located on the island of Heimaey.

In some places around the volcano, the lava is still hot today and can be used to slow-bake rye bread overnight. Exploring the islands with a local expert on one of many Westman Islands tours is the best way to get the full experience, and you can enjoy a stay at one of the great accommodations in Heimaey.

- Learn about the Top Things to Do in the Westman Islands (Vestmannaeyjar)

The Krafla Fires (1977-1981)

Image from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Michael Ryan.

Krafla began stirring again late in 1975, with the first of a decade-long series of eruptions known as the Krafla fires. This period was marked by numerous eruptions, ground deformation, and seismic activity. At the time, work was well underway on the Krafla power station.

Older Icelanders have strong memories of the Krafla fires as the national news station closely monitored and televised them. Many people also flocked to the eruption sites to witness the natural powers at work with their own eyes.

21st-Century Eruptions in Iceland

While we are still early in the 21st century, there have already been quite a few noteworthy eruptions that garnered international attention - for better or worse. Fortunately, they have not been nearly as devastating or costly to human lives as most of the previously mentioned eruptions.

Eyjafjallajokull (2010)

Image from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Bjarki S.

Quickly earning a reputation as the world's most notorious volcano, Eyjafjallajokull erupted in 2010, generating a vast plume of ash that spread as high as 6 miles (9 kilometers). The ash cloud, carried by winds, spread across much of Northern Europe, leading to the largest air traffic shut-down since the Second World War.

The closure lasted for about a week due to concerns that the fine ash could cause severe damage to jet engines. The disruption affected about 10 million travelers and caused significant economic loss, with the airline industry alone losing an estimated 1.7 billion dollars.

The international media found it difficult to pronounce the volcano's name, which is quite a mouthful. Trying to say Eyjafjallajokull became a viral trend globally, with Icelandic people posting their own videos and instructing people on the correct pronunciation.

The eruption officially ended in October 2010, but the people affected by Eyjafjallajokull's disruption are unlikely to forget the volcano any time soon. Today the area can be explored on an exhilirating snowmobiling tour on Eyjafjallajokull glacier.

Grimsvotn (2011)

Image from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Calistemon.

Grimsvotn is a partially subglacial volcano located beneath the Vatnajokull ice cap. It is Iceland's most active volcano, boasting over 70 eruptions in the last millennium. The plinian eruption that began in 2011 was powerful and intensified due to the interaction between magma and glacial water, which led to a significant production of ash.

The ash cloud from the Grimsvotn eruption reached up to 12 miles (20 kilometers) in height, substantially higher than the one from the Eyjafjallajokull eruption in 2010. However, due to differences in ash composition and weather patterns, the disruption to air travel was much less severe than in the 2010 event.

Image from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Calistemon.

The eruption caused local disturbances as the ash covered large sections of land. Thankfully, the response from authorities was well-managed, and cleanups were quickly organized to minimize the damage to farmers. The ashfall led to minor health concerns and temporary disruptions, but people quickly returned to their daily lives. The eruption lasted for just about a week.

Holuhraun (2014-2015)

Bardarbunga is Iceland's largest volcanic system, running around 125 miles long (200 kilometers) and up to 15 miles wide (25 kilometers). It was lava traveling from Bardarbunga's magma chamber that caused an eruption in the volcano of Holuhraun in 2014.

The eruption started slowly but quickly picked up pace, covering a large area in a sea of lava flowing out from multiple fissures. After three months, the amount of lava released was greater than any seen in an Icelandic eruption since the one in Laki in 1783.

While no human lives were claimed in the eruption, livestock perished due to the poison fumes released. The gas pollution was a concern for public health, and warnings were issued on days when the gas levels were particularly high.

The eruption lasted for almost six months, greatly enlarging the area of the Holuhraun lava field.

Fagradalsfjall (2021)

The eruption of Fagradalsfjall in 2021 did not surprise the people of Iceland, who were quite literally shaken after having endured over 50 thousand tremors in the preceding weeks, many of which were felt in Reykjavik. While most of these quakes could not be felt, people still sighed a breath of relief.

The eruption began on March 19th when a fissure up to 0.4 miles (700 meters) long opened up in the Geldingadalur Valley. The location of the eruption was convenient, as it was secluded and did not threaten any settlements or infrastructure. The eruption was also effusive, as opposed to an explosive one, meaning that the lava flowed down in gentle streams.

This was a rare event, as the Reykjanes Peninsula hadn't experienced any volcanic activity since the Reykjanes fires 800 years earlier. People from all over the world flocked to Iceland to bear witness to the spectacle, and the eruption site became one of the country's main attractions. As pictures will tell, the eruption was quite a sight to behold and lasted for roughly six months before dying down.

Fagradalsfjall (2022)

The Fagradalsfjall eruption did not remain quiet for long as the volcano erupted again on August 3, 2022. This time, the rift zone was located in Meradalir valley, about 0.6 miles (1 kilometer) from the previous eruption site. As with the previous eruption, it was preceded by multiple tremors.

Again, people flocked to see Fagradalsfjall and its volcanic splendor, but the eruption was much shorter than the one before, lasting only for three weeks. Even so, the location remains a popular attraction as the aftermath of the eruption is quite a sight to behold in itself.

Litli-Hrutur (2023)

In the summer of 2023, the Reykjanes Peninsula started shaking once more before a rift opened on July 10th by the small mountain of Litli-Hrutur. This new fissure measured half a mile long (900 meters), and the eruption started much stronger than the eruptions in Fagradalsfjall. The eruption lasted for just under a month, ending on August 5th.

The Litli-Hrutur eruption was located a couple of miles northeast of the 2022 eruption in Fagradalsfjall. The round-trip hike to Litli-Hrutur is on the long side, ranging at roughly 14 miles (20 kilometers). Although the eruption is over, visiting the eruption site is well worth the opportunity to see the aftermath of the spectacular natural powers at play.

Sundhnukagigar (2023-2025)

The latest additions to Iceland's ever-growing eruption history are courtesy of Sundhnukagigar, a historic row of craters that last erupted 2,500 years ago, shaping much of the surrounding landscape just outside the town of Grindavik.

The latest additions to Iceland's ever-growing eruption history are courtesy of Sundhnukagigar, a historic row of craters that last erupted 2,500 years ago, shaping much of the surrounding landscape just outside the town of Grindavik.

From December 2023 through 2024 and into 2025, there were multiple eruptions in the Sundhnukagigar craters. These eruptions differed from earlier events because of the impact they had on the local community.

While the eruptions did not affect international flights or general travel to Iceland, and daily life continued as normal for most Icelanders, the Sundhnukagigar craters are located just outside Grindavik, and the town remained mostly uninhabited during much of this period.

Before the first eruption in 2023, the town suffered significant damage from intense earthquakes beginning on October 25th. Fears that the eruption might occur directly beneath Grindavik led to an evacuation on November 10th, and in the following weeks, residents managed to rescue animals and retrieve personal items. Due to these measures, the town was deserted when the first eruption eventually occurred.

On the evening of December 18th, 2023, a new 2.5-mile (4-kilometer) fissure ripped open on the Earth's surface by the old Sundhnukagigar craters, spewing lava over 328 feet (100 meters) into the air. This was the fourth chapter in the series of eruptions on the Reykjanes Peninsula in the area around Fagradalsfjall.

On the evening of December 18th, 2023, a new 2.5-mile (4-kilometer) fissure ripped open on the Earth's surface by the old Sundhnukagigar craters, spewing lava over 328 feet (100 meters) into the air. This was the fourth chapter in the series of eruptions on the Reykjanes Peninsula in the area around Fagradalsfjall.

The Sundhnukagigar eruption quickly surpassed the scale of the previous three eruptions in the area. Remarkably, in just the first seven hours, it exceeded the total lava volume of the entire month-long Litli-Hrutur eruption, which itself was significantly larger than the nearby eruptions of 2022 and 2021. However, it thankfully started slowing down in the first 24 hours before coming to an end on the morning of December 21st.

The lava flow from this Sundhnukagigar eruption did not pose a direct threat to Grindavik or the nearby infrastructure of the Svartshengi geothermal power plant and the Blue Lagoon.

Great measures were taken to build protective barriers around the town and other important infrastructure to stop the potential flow of lava. These measures would come to be incredibly important for the following eruptions.

This December eruption marked the start of a series that experts have started calling the "Second Reykjanes Fires," the first ones having occurred between 1210 and 1240.

This December eruption marked the start of a series that experts have started calling the "Second Reykjanes Fires," the first ones having occurred between 1210 and 1240.

It wasn't long until the next Sundhnukagigar eruption took place, with the earth opening again by Hagafell mountain on January 14th, 2024.

It did not pose a risk to locals as the area was fully evacuated, but unfortunately, the fissure reached the edge of town and went through one of the protective barriers. This led to three houses being destroyed in the eruption, but thankfully, the lava flow stopped before more damage could occur.

The eruption by Hagafell mountain would come to an end on January 19th, and the following volcanic eruptions would have far less effect on locals and the nearby infrastructure.

- Learn more: Complete Guide to the 2024 Hagafell Volcanic Eruption Near Grindavik

- See also: Geothermal Power in Iceland

Another eruption began in Sundhnukagigar on February 8th, 2024. As this eruption was located further from Grindavik than the eruption in Hagafell a month before, it did not pose a direct danger to the town, but it did damage infrastructure in the area as the molten lava flow burst the main hot water pipe for the Reykjanes peninsula.

Another eruption began in Sundhnukagigar on February 8th, 2024. As this eruption was located further from Grindavik than the eruption in Hagafell a month before, it did not pose a direct danger to the town, but it did damage infrastructure in the area as the molten lava flow burst the main hot water pipe for the Reykjanes peninsula.

As hot geothermal water is used to heat houses around Iceland, this left homes in the surrounding region without hot water and heating for four cold winter days. Repairs were quickly made, the waterpipe was repaired, and special protection was added to prevent similar incidents in future eruptions.

This eruption was relatively short and was officially declared to have ended on February 10th.

The next eruptions of Sundhnukagigar had little effect on daily life in Iceland. The fourth one lasted for a relatively long time compared to the previous Sundhnukagigar eruptions, starting on March 16th and ending on April 5th.

The next eruptions of Sundhnukagigar had little effect on daily life in Iceland. The fourth one lasted for a relatively long time compared to the previous Sundhnukagigar eruptions, starting on March 16th and ending on April 5th.

Lava from this eruption flowed into the nearby Melholsnama mine, which had been used to source materials for building protective barriers in the area, rendering it unusable. Otherwise, it posed little risk to nearby infrastructure and did not affect most of the local population.

The fifth eruption would start on May 29th, and it was the most powerful one so far. Lava went over the Grindavikurvegur and Nesvegur roads and over one of the protective barriers. Water was used to stop the lava flow, and locals were able to repair the barriers before any damage could occur. It finally came to a close on June 22nd.

The sixth eruption of Sundhnukagigar differed from the rest as it was located further north, away from Grindavik. This was a much better position when it came to protecting nearby infrastructure, but it did raise some new challenges.

The sixth eruption of Sundhnukagigar differed from the rest as it was located further north, away from Grindavik. This was a much better position when it came to protecting nearby infrastructure, but it did raise some new challenges.

The eruption started on August 22nd, and lava flow spread over new areas, including an army practice site used by the United States between 1952 and 1960. Hidden among the 13th-century lava fields from the First Reykjanes Fires are remains of weaponry, including active landmines.

While the area has remained closed throughout the eruption process, there were concerns about curious risk-takers ignoring the closure and putting themselves in danger by hiking through the area.

Thankfully, the safety closure was respected, and no one was harmed trying to reach the eruption. It finally came to a close on September 5th.

In the weeks afterward, lava continued collecting under the surface, but another eruption wasn't expected until at least the start of December. It was then with surprise that the seventh eruption started right before midnight on November 20th, with very little warning. This marked the tenth eruption in four years on the Reykjanes peninsula.

In the weeks afterward, lava continued collecting under the surface, but another eruption wasn't expected until at least the start of December. It was then with surprise that the seventh eruption started right before midnight on November 20th, with very little warning. This marked the tenth eruption in four years on the Reykjanes peninsula.

The volcanic fissure opened in a similar spot as the August eruption, further north of Grindavik, and was less powerful. While it did not pose direct threats to the Svartsengi powerplant or the Blue Lagoon itself, the lava flowed over nearby roads and covered the main Blue Lagoon parking lot, burning down a small storage house on its edge.

Thankfully, the Blue Lagoon was able to resume operations as normal shortly after, as it was protected by barrier walls that have proven effective in stopping lava flow. The eruption soon slowed down but remained steady for 18 days. It was declared to be over on December 9th.

As 2024 turned into 2025, the next eruption began on April 1, which became one of the most recent events in the series. At around 7:30 AM, the ground near Grindavik began to tremble as lava pushed its way toward the surface.

As 2024 turned into 2025, the next eruption began on April 1, which became one of the most recent events in the series. At around 7:30 AM, the ground near Grindavik began to tremble as lava pushed its way toward the surface.

The molten rock traveled more than 6 miles (10 kilometers) underground before finally breaking through around 9:30 AM. Compared to previous eruptions, this one was smaller in scale, but notably closer to Grindavik than usual.

Part of the fissure breached one of the town’s protective barriers. However, because the eruption was relatively weak, the lava did not reach Grindavik itself. By April 2nd, activity had come to a stop, though the area still experienced small earthquakes.

At 4 AM on July 16, 2025, an eruption began along the Sundhnukagigar Crater Row. It followed a burst of strong earthquakes just before midnight. This marked one of a series of eruptions at Sundhnukagigar and the twelfth volcanic event on the Reykjanes Peninsula since 2021.

The eruption site was located southeast of Litla-Skogfell Mountain. As a precaution, the Blue Lagoon and the campground in Grindavik were evacuated; however, according to a natural hazard expert from the Icelandic Meteorological Institute, the location of the eruption is considered very favorable.

It is far enough from key infrastructure that it would need to last for a considerable time before posing any threat to existing facilities. For the first time, a hiking path was also established to the Sundhnukagigar eruption site, meaning visitors could now see the lava for themselves.

The eruption lasted unusually long compared to the other ones in 2025, coming to an end on August 5th.

Overall, all the Sundhnukagigar eruptions follow a similar pattern. Most have been preceded by a wave of small earthquakes before a powerful fissure opens up.

In the first hours, they reach lengths of 1 to 2.5 miles (1.5 to 4 kilometers) before slowly losing power and forming into craters. Lava flow remains steady but slow before activity stops. Then, magma starts collecting under the surface again until it creates enough pressure to break through the earth, starting yet another eruption.

The whole area around Sundhnukagigar may be temporarily closed off for safety. Please respect any safety closures and check the SafeTravel website for updates.

If you don't want to miss out on seeing the eruption area, you can see the Sundhnukagigar craters up close with the volcano shuttle service, or for a special adventure, take this helicopter tour of the volcano site. If you're staying in a hotel in Reykjavik, this is a convenient addition to your itinerary as it departs from Reykjavik Domestic Airport.

That's our brief overview of the history of eruptions in Iceland. Did we leave any questions unanswered? Did we leave out an eruption you think belongs on the list? Be sure to let us know in the comments below!